Rutgers Law Review

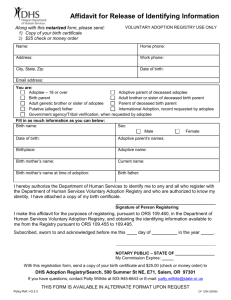

advertisement