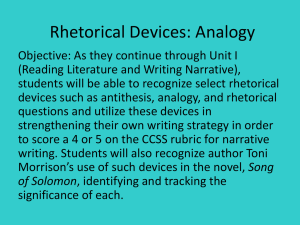

The study of analogy is a good example of the practical and

advertisement

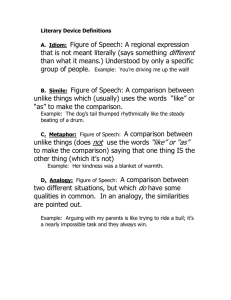

Amity to Malice Analogies taste much like chicken. Or, why your thesaurus is like a tapeworm Analogy is a comparison of features, parts, or aspects of things in order to compare the nature of those things. For those of you who are occasionally uncertain about what to write, or what is written, or how it works, or how to understand it, the short answer is often: an analogy. Mastering the analogy is troublesome, because it isn’t content; it’s the way to package or organize the content. Analogies are a cognitive process; some people think they are the cognitive process. It’s an intriguing idea: analogy underlies nearly everything concerned with thinking. Whether this is true or not, analogies are like rhetoric—a way of thinking, rather than stuff to think about. This course will be based in large part on the concept of the analogy. We’ll start with one simple form: vocab analogies. These nasty little devices are most commonly found as test items; they used to appear in the verbal section of your local SAT or ACT. When well done, vocabulary analogies are a devilishly clever reckoning of two concepts against each other, perhaps the toughest of all multiple-guess questions in the realm of writing and thinking: Malice : Indifference :: Amity : Bitter Cordiality Apathy Truculent Word analogies are difficult because they seem ambiguous. Students and schools mistrust ambiguity, mainly because it’s hard. But in vocabulary analogies it isn’t the question that’s ambiguous; it’s the words. Which is, of course, what these items are trying to measure. This is true because ambiguity is natural, even desirable in vocabulary (but not in tests!) There are many variables within the relationships between two words, especially two words which are close in meaning. That should make sense. The closer in meaning two words are the more challenging it is to understand them. No matter how hard teachers work at it, they can’t screen out the ambiguity in words without screening out the value. Those shades of meaning are the main source of nuance, precision, beauty, and originality for writers. But precision and beauty and so on are trouble on tests. That’s why vocab analogies are gone from most high stakes tests. When confronted with new vocabulary, lazy students (imitating Antony and Cleopatra II-2 their lazy teachers) simply equate the new word with a word they OCTAVIUS CAESAR already have. Taken far enough, that process consigns the student to Say not so, Agrippa: a paradox in which the more words they know the less clearly they If Cleopatra heard you, your reproof can express themselves. As writers you are better off with a Were well deserved of rashness. thorough understanding of a few words than a cursory understanding of many. MARK ANTONY I am not married, Caesar: let me hear Take ‘amity’. A thorough study of this word would lead to a series Agrippa further speak. of overlapping or related definitions clustered around the concept of friendly relations. Amity is something like friendliness, more like AGRIPPA friendship, but also cordiality, or maybe “warm-heartedness towards To hold you in perpetual amity, To make you brothers, and to knit your hearts neighbors”. It’s like (but not the same as) amigo, amo amas amat With an unslipping knot, take Antony etc., amour, and a bunch of other foreign source words and borrow words. But it isn’t like ‘amend’ or ‘ammonia’ or ‘American.’ Such a Octavia to his wife; whose beauty claims No worse a husband than the best of men; lot of thinking and reading and study for one little word! A student Whose virtue and whose general graces speak who has not coped with ‘amity’ in context will have little hope of That which none else can utter. using it well in writing. Simple study of the word will probably equip a student to get the item right on a test—provided the test doesn’t rely on analogy to measure the nuanced definitions of the word. The new analogy-free tests don’t want to measure you as a writer. They want to measure you as a test-taker. The old-school purpose of vocabulary analogies was not to measure whether the student knew the meaning of the word “amity.” That purpose was to test whether the student could manage subsets of the meaning of one word—“amity”—against a variety of other questions. Do you know the meaning of the other words in the item? Do you notice that the words in the item are not all the same part of speech? And, most importantly—how might ‘amity’ figure in the relationship between ‘malice’ and ‘indifference?’ To solve this analogy the student must determine the relationship Richard III I-3 between the two words in the first set. But, because they are words, there will rarely be a whole relationship in which the words are BUCKINGHAM opposites or synonyms. Vocabulary analogies in which there is a simple, Have done, have done. unambiguous relationship between the first two words are too simple. QUEEN MARGARET Very few words have a whole relationship; if they did, their meanings O princely Buckingham I'll kiss thy hand, would change or the words would fall out of usage even in a shaggy, In sign of league and amity with thee: gluttonous, and inefficient language like English.* Now fair befal thee and thy noble house! In a well written vocabulary analogy, the relationship is an abstraction. Thy garments are not spotted with our blood, The student must posit a context for the relationship then apply the same Nor thou within the compass of my curse. context to the target word—here, ‘amity.’ Some contexts are reasonable for the two words but faulty when applied to the options. Had a student been extensively trained in the latin and greek roots, he might correctly notice in the item above that ‘malice’ is cognate to the Spanish for ‘bad’ and ‘amity’ is related to the Spanish for ‘friend.’ That student might then notice that ‘Indifference’ is related to the French for ‘different’ and choose ‘truculent’ as the answer most related to a French word. That would be a cockamamie call for this item, but its logic would not be faulty. In this case the relationship might best be described by filling in a sentence so the words are the best possible words for the situation, and the two sentences match. Absence of malice, and absence of the opposite of malice which is benignity, is best described as indifference. Absence of amity, and the absence of the opposite of amity which is discord, is best described as apathy. As any teacher who has ever gone over an analogy test with a disputative class knows, such explanations are red meat, especially to children (and their parents) who are just a tenth of a point away from the A. It is useless in that situation to point out that falling just short of a goal is good for the character. Standardized tests feature few vocabulary analogies any more. One might say that ambiguity has led this softheaded generation (of teachers and, therefore, of students) to back off the tangy challenge of the vocabulary analogy. We are now safely definite with items like this: 4. What is the meaning of amity ? a. mutual opposition or resistance of counteracting forces, principles, or persons. b. that which is thought; an idea; a mental conception, whether an opinion, judgment, fancy, purpose, or intention c. friendship. d. prone to anger. e. dissimilarity in any respect. This item is much easier, because (in true modern educative fashion) it isolates the purpose of the item to one process: recall the meaning of the word ‘amity.’ When that practice is writ large across all thinking, it makes for simple, easily-understood test scores and for simple, easily-understood thinkers. The writer would say, (and the reader would agree): it isn’t enough to recall ‘amity’ in a single unambiguous synonym. Nothing is exactly the same as anything else. That fact is inconvenient in most situations, including conferences with administrators. Students have a natural, reasonable tendency to equate all words across the spectrum of vocabulary, and to study vocabulary by the thesaurus method, in which we learn the meaning of word A by equating it (rather than the more complex process of relating it) to word B. Therefore ‘amity’ equals ‘friendship,’ thinketh the student, and in some future situation where the student hopes to punch up the appeal of an essay or story he pauses * If a trope compares without the word “like,” it isn’t an analogy but a visitor from a higher realm of abstract comparison called metaphor. If the trope mixes comparisons, such as ‘shaggy’ (unkempt, poorly tended, overgrown, disorganized) and ‘gluttonous’ (overfed, greedy, insatiable, overindulged, excessive) and ‘inefficient’ (unambiguous; not used figuratively), then it falls into a special category called a “mixed metaphor,” which does not reflect well on the writer and is a form of logical fallacy. English, however, can be compared–-is like—a shaggy, inefficient glutton, so the phrase is odd but not a failure.) before writing the word ‘friendship’ and instead plunks down the word ‘amity.’ However. Amity is not friendship. Both words are embroidered with abstractions that tint them and shape them into very different things. There are hundreds of ways to comment on the difference between the two words. Friendship is a close relationship that is explicitly not romantic and not sibling; it is often used to describe a connection of heart or mind that centers upon casual activities such as play or relaxation; it can be maintained over distance or time then rekindled. Amity means peaceful coexistence and mutual understanding; it is more a matter of indifferent acceptance or geographical relationship than hanging out and borrowing money from each other. Furthermore ‘amity’ is clunky and overformal in our current usage and though it is a noun as is ‘friendship’ they can’t be substituted comfortably in all situations for each other. ‘Amity’ was the name of the seaside town that served for a time as the buffet for a 25-foot shark in the film ‘Jaws.’ Does that change the word’s meaning? For a good writer it very well could. Friendship, you might notice, is a clunky noun formed by taking the particular person ‘friend’ and distilling the thing that defines it into the nauseatingly vague suffix ‘ship.’ (I hope your studentship yields some strong writership.) Amity is much less common in usage than its adjective cousin ‘amicable’. And so on. (by the way, the use of “and so on” or “etc.” is itself an analogy. Do you see how?) The relationship of the two words is not definitional; it’s an abstraction based on elements of meaning, derivation and etymology, usage, cadence, and grammar. Their relationship is more like the long-established cordiality of two very different neighbors. It’s more like amity than interchangeability. Burn your thesaurus. When you turn to your thesaurus, you are committing an intellectual error. The very act of looking through a thesaurus modifies the meaning of the word you began with. I call it “thesauriasis.” It is better to know simple words well than to know many words weakly. In rhetoric and philosophy, the analogy is broken down into its component parts. The starting idea, object, or situation is called What time is it? the analogue or source; the object to be explained is called the target. This is complicated a bit by the linguistic process of Why is this type of transferring information from the source to the target, since clock called typically in English the target comes first, since that’s the thing “analog?” we’re talking about. Consider a weird, complex idea that you (the writer) is trying to explain. That’s T, the target. The audience doesn’t get the target. If the audience already understands the target and your goal as a writer is to get them to understand the target then you don’t need to do any writing. You are preaching to the choir. But if they don’t get it, then the writing needs to be done. The audience needs needs you to explain T. A common strategy for the writer would be to cite a source (S) in an analogy to create a basis for understanding. The word “like” is the grammatical glue that holds the two together. Your essay looks like this: In this essay, I will explain T. You are my audience. I have determined that you don’t understand T but you care enough about it to read this essay. I have determined that my authority and attributes as a writer are a good match for you. The true and essential abstract nature of T is X. X in itself is unexplainable, ineffable, intangible, or otherwise useless to explain T. So declaring X=T or enlarging upon the Xness of T won’t work for you (plus I’m getting paid by the word.) So be ready: my explanation of T will take the form of the rhetorical structure called Analogy. Behold S. You already understand S in its own context. Fair warning: I am seizing S for my analogy. Now that you are prepared for me to analogize upon S, note that it has these characteristics: S1, S2, and S3. S also has characteristics S4 through S266 but I don’t need those. I may need you to ignore some of those so my analogy doesn’t fail, but for now consider only S1, S2, and S3. I think you’ll get a better sense of X by thinking about S and T, but don’t worry about that. Get ready. Here comes the analogy proper. T is like S. S has characteristics S1, S2, and S3; T has T1, T2, and T3. S1 and T1 match up in these ways. S2 and T2 match up in these ways, with a few variations, and some crossover to S1 and T3 that isn’t a dealbreaker. S3 and T3 are different in the same ways, which is actually instructive of the nature of T in these ways. T=X, X is like S1, S2, and S3. T is like S1, S2, and S3 too. Now you know what T is. Or, for example: It’s hard for people to understand the appeal of gliders. Part of that appeal, of course, is the general appeal of flight. People who fly gliders are after a purer, deeper experience of flight, but if you have little or no sense of what flying is like, I’ll have to build an analogy to explain why glider pilots are so passionate about their strange little machines. Gliders, or ‘sailplanes,’ are airplanes in every sense but one. They have Bernoulli-effect lifting bodies—commonly called wings—and stabilizing and steering bodies, usually called rudders and stabilizers. They have a passenger compartment and a set of controls that look much like what you’d find in any Cessna. But what sets the sailplane apart is the desire of the pilot to experience a kind of pure flight that transcends the noisy, complicated business of runways and takeoffs and fuel mixtures and waveoffs. Sailplanes are truly defined by what they lack; in our acquisitive, power-mad culture, a sailplane is an insanely powerless vehicle. And that’s just the way we like it. A sailplane is like an airplane; they both have wings, and a person can ride in them safely and comfortably; but an airplane travels under its own power while a sailplane only glides. Furthermore, the sailplane wants to glide, and is designed to glide, and glides beautifully and consistently and for a long, long time; for the airplane gliding is a last dangerous resort. Therefore for a sailplane, gliding is flying; for an airplane, gliding is a kind of crashing. (veterans of literature classes will recognize these statements as the poetical or rhetorical device simile. Simile, like all rhetorical devices, can be tracked or mapped logically, and it works in poetry or writing because of the intellectual character of analogy—that is, the capacity to comprehend analogy has resulted in our ability to comprehend simile. Metaphor is a different and more demanding intellectual process, but is also the writerly manifestation of a natural thought process of comparison.) It’s easy to see how an essay might become a sequence of analogies, and indeed many essays can be broken down that way. This is especially apparent if you recognize that nearly all processes of converting reality into words rely on analogy, and that words are themselves a kind of analogy. Use analogy as the basis for your essays. When you write always have an analogy in mind even if you don’t try to develop it. Perceiving and evaluating the analogy in an essay is an excellent way to develop a rhetorical analysis of an essay beyond a simple listing of the writer’s techniques. In fact, if you gain one thing from this essay, it should be this question: ‘what’s the analogy?’ Ask yourself that question over and over. (an answer might be: analogy is the analogy. He is trying to use analogy and teach it at the same time.) “Comparison” essays are clearly analogy; A is like B. But that means that the “contrast” essay is also an analogy inverted—A is unlike B. A proposal essay in which the writer contends that if certain measures are taken certain results will follow will usually be based on evidence that is analogous, as in this example: The Canadian healthcare system succeeds in finding and treating health issues before they become expensive, by encouraging all people regardless of income level to take simple preventive measures including checkups and assessments. A universal, single-payer system will therefore improve the health and well-being of those Americans who need it most and will save money. This assertion rests on at least two analogies: that the American system being proposed by the writer would function like the Canadian system does at present; and that that American system would be better for one certain segment of the population and for the nation in general. This essay also might open up numerous conditions of rebuttal in analogy form—that is, places where the analogy fails and therefore the proposal should be rejected. All analogies are vulnerable in this way.) If the American health care requirements were different from the Canadian ones—if, for example, Americans and Canadians had very different physiologies—then the target and source are not analogous and the analogy would be faulty—an “apples and oranges” rebuttal. An attentive student might begin here to see the possibility of a counterargument relying on analogy: The analogy fails because Americans would never accept it, therefore it’s moot whether it would work. Americans are highly individualistic, and so are like… . Any time you suggest something, you are offering an analogy that relies on the potential for future result. “If you touch that red hot object, it will hurt,” you say to the child. The child has not so far touched that hot object, but the child is familiar with the concept of pain, so the child doesn’t touch it. The child has learned by analogy. If the child then extends the analogy to all hot objects, further analogous learning has occurred. The child might also decide—analogously— that all red objects are hot, and hesitate to touch them. That too is logical, though faulty, and would require more analogies to refine the understanding of the child about hot objects that are not red and red objects that are not hot. Or, the reverse. My wife recently cooked a delicious egg dish that was baked in a skillet. Skillets are stove-top pans, hence the long handle which usually makes touching them safe, for reasons that relate to physics. They aren’t usually used for baking, which makes the whole pan hot, for those same reasons relating to physics. When the skillet came out of the oven it still looked like that same old thing I had been safely grasping by the handle since the Clinton Administration. That explains why I confidently grasped the handle to carry the skillet to the table. I should mention here that my wife had told me that she was baking a delicious egg dish in a skillet. I had seen her take it out of the oven. I am of at least average intelligence and experience in the kitchen. Yet none of the ‘hot handle!’ evidence was active enough in my consciousness to challenge or override my decision to grab it. The first input active enough to override that decision was the pain of the second degree burn on the palm of my hand, or maybe the stench of frying flesh as the second degree burn graduated to third degree. The skillet’s shape and its usual practical use had conditioned me to see it as not analogous to a hot baking pan, which overruled in my mind the ample evidence that grabbing the handle was a bad idea. Essays of definition are also based on an analogy—the contention that a word can contain the meaning of an idea. Choosing a set of words to describe an idea, or arguing that a word no longer defines an idea, is offering an analogical debate. Since words denote meaning arbitrarily, they function as something below analogy. We have agreed that the word “ankle” denotes the region of the leg between foot and shin. Ankle has no essential relationship to that part of the body; it’s just what we call it. The choice of “ankle” has no merit other than the fact that we agreed to use it a while back and most people who speak English have already accepted it. If the concept denoted by “ankle” were to change, we might need a new word for it. If a writer had a need to reset the assumption, he could do it easily because there is no inherent value in the word ‘ankle’ other than as an agreedupon denotation of the joint that connects foot and leg. But that part of the leg is more than a space between two other parts; it has other identities. If the foot of the writer were blown off by an IED while he was on patrol in Fallujah, that writer might have a new definition of “ankle.” It becomes something else—something like a foot, and something like a stump, and something like a badge of honor, and something like a handicap, and something like a connection between the living body and the plastic-and-steel prosthetic foot, and something like a reminder of the friend who died in the same incident, and something like the last link to a part of the body that is no longer there, but still occasionally reports back to the brain, etc. That writer might tell the story of the injury “straight”—with no analogy—but the use of an analogy creates an intellectual link to the reader. If I set out to redefine “ankle” as a way of discussing the nobility of sacrifice for ones country, I have embarked on an extended analogy. Even personal essays are analogy-based. The central analogy in any writing is the analogy between the writer and reader. The entire enterprise is based on the transfer of the untransferrable: my feelings, my understanding, my knowledge is transferred to you. If you understand it, you understand me in smaller or greater ways. Personal essays deal in those essential traits of humanness that can’t be equated, can’t be measured in any reliable way. We use abstractions to describe them in general terms: I love you. I miss you. I feel angry. I feel like my whole life has been wasted. A frequent criticism of such essays by young writers is that the student conveys abstractions with abstractions. This is the equivalent of defining a word with itself: Amity is when you feel a lot of amicableness for a person. Unfortunately for the writer, nearly everything worth discussing is an abstraction. If you have no tools to breach the personalness of an idea, you are stuck defining a thing in terms of the thing itself, or chasing the idea in circles. The solution: convey abstraction in writing is through analogy. Consider an essay on falling in love. There are no simple equations that make a persuasive description of love: I was totally in love. Head over heels in love. I loved her, like, a lot. Whoo-ee, did I love that girl. I was experiencing strong emotions. Love was what it was. I was in love. Introduce an analogy, and you are in business: Love for me was like a liberation, a long-awaited but still unexpected appearance of friendly troops. I knew that my heart was damaged, that the corrosion of hatred and bigotry had reduced my ability even to recognize other people as human. But I had not seen it as a conquest until the day our tanks rolled in and the occupiers fled to the hills. The avenues of my heart were suddenly open to me, and with the others I wandered dazed through the damage. Once I was free, I became human again; once I was human, I found myself in love. Throughout this course we will be analyzing all of our work in terms of analogy. Be prepared!