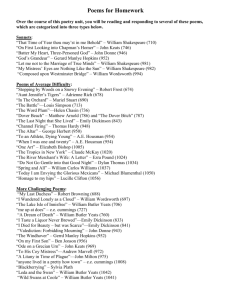

Easter 1916 by W

advertisement

Easter 1916 by W.B. Yeats Structure: First stanza - The poet’s mocking attitude to the would-be revolutionaries before the 1916 rising. He has “polite meaningless words” with them when he meets them, but makes up “a mocking tale or gibe” about them to share later with his own friends “around the fire at the club”. However, he has had to reassess his attitude in the light of the 1916 rising - up to then he thought they were just playing around (“motley”), but now everything is “changed, changed utterly”. Second Stanza - He outlines the different situations of some of those involved in the rising: e.g. 17-23 he deals with Constance Markiewicz who has been coarsened by her political involvement: “her voice grew shrill”; 24-30 refer to Pearse and McDonagh, and he seems to regret the lost potential of McDonagh as a fellow writer: “He might have won fame in the end/ So sensitive his nature seemed”; 31-40 refers to Major John MacBride, who has been transformed in Yeats’ jaundiced estimation from being “A drunken, vainglorious lout” to someone who “has been changed” and has taken a serious role in life (“resigned his part/In the casual comedy”). Third Stanza - he compares the single mindedness (or fanaticism?) of the patriot (“one purpose alone”) to a stone, and contrasts this with the liveliness and ever-changing variety of nature: “From cloud to tumbling cloud,/Minute by minute they change”. Fourth Stanza - he further reflects on the nature of total dedication to one cause: “Too long a sacrifice/Can make a stone of the heart”. He wonders how much a dedicated person must give (“O when may it suffice?”), does it have to be to the point of death, when things might be resolved in other ways? (“Was it needless death after all?”). Again he wonders if the sacrifice was worthwhile (“what if excess of love/Bewildered them till they died?”), but in this stanza concentrates on what he is sure of: “they dreamed and are dead” and he is sure that things will never be the same again: “changed utterly”. Theme: Change is obviously central (note the repetition of “changed utterly”) His own attitude to the rebels has changed - up to now he mocked them (10), but now he knows they were not playacting (13-16, 36-38). And the patriots themselves have changed (38, 71). So has the attitude of others “wherever green is worn” (78). Yet Yeats’ attitude is ambiguous despite the changes brought about by the rising he realises that paradoxically fanaticism/dedication can stifle change, it can turn people to stone (57-58) and make them rigid and inflexible despite all the lively change (“Changes minute by minute”) in nature around them (3rd stanza). The image of “a stone/To trouble the living stream” (43-44) captures his ideas here as does the paradoxical image of the “terrible beauty”. Yeats also considers the nature of dedication: “too long a sacrifice/Can make a stone of the heart”. It can make people rigid, inflexible, coarse (as with Constance Markiewicz (17-23), and misguided (“ignorant good-will” - 18). It can waste talent as in McDonagh’s case (“He might have won fame in the end” - 28) and yet can transform others for the better, as in McBride’s case: from being “A drunken, vainglorious lout ... He, too, has been changed in his turn”. It fulfils people’s dreams yet makes them dead: “they dreamed and are dead” (71). Judgement could also be said to be a theme - Yeats has to re-examine his judgement of these revolutionaries, but isn’t too sure of his new judgement - as indicated above he can see good and bad sides to what has happened. Perhaps he is too near in time to the event to make a definitive judgement at this stage. Links/Comparisons: This is yet another of Yeats’ political poems. Like September 1913 it is set at a particular place and time, responding to a different set of circumstances. In S13 he was very critical (of the merchant middle classes in that case). Now he is more reflective, but there is only a touch of criticism here in his now redundant assessment of McBride (“A drunken, vainglorious lout”), but now perhaps “Romantic Ireland” is no longer “dead and gone”. Whereas in S13 he named the old dead heroes like Tone and Emmet, now he can name contemporary heroes, though some of them also have just died - “MacDonagh and MacBride/ And Connolly and Pearse”. He is not unreservedly enthusiastic about what they have done, but knows that things have “changed utterly”, and his image of the “terrible beauty” captures his ambiguous attitude towards the change and the way it came about. – ambiguous as he is uneasy about the fanaticism involved “too long a sacrifice/Can make a stone of the heart”. Maybe it’s easier to glorify past heroes, but harder when they’re of your own time, and you know some of them including some who have “done most bitter wrong/To some who are near my heart”. In many of Yeats’ poems there is a tension between real and ideal – eg in S13 between the old Romantic Ireland and the new materialistic Ireland. Here in a sense the ideal has reached out to become the real (the action of the 1916 leaders to bring their ideals into reality). But in another sense it’s not as ideal as Yeats might have thought in S13 – he outlines the downside to the achievement – i.e. the excesses of fanaticism. As in The Wild Swans at Coole and Sailing to Byzantium, in E16 nature is also used more for symbolism. Once again there are bird references (“the birds that range”) 07/03/2016