When the Heart Is Held Hostage: Yeats on Love From the time of

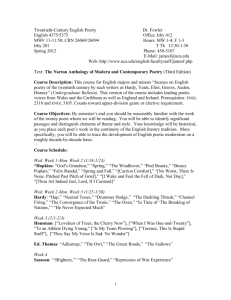

advertisement

When the Heart Is Held Hostage: Yeats on Love From the time of knights in shining armor and fair ladies waiting faithfully for their return, love has been interpreted as an all or nothing proposition. This popular notion is reinforced by the sacrament of marriage, where couples vow total devotion to each other “for better or for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health… ‘til death do us part.” With his poem, “Never Give All the Heart,” however, the Irish poet William Butler Yeats sounds a cautionary note about the hazards of giving all of yourself to another in the name of love. The title “Never Give All the Heart” sets the tone of the poem, as Yeats uses the sonnet form to argue that doing so might lead to devastating loss and pain. First, though, he fully concedes the power of love. In line 10, he compares love to “a play,” and then, in a rhetorical question of sorts, writes, “And who could play it well enough / If deaf and dumb and blind with love?” (11-12). It is apparent that Yeats himself fared poorly in this drama, for the poem is clearly written as a postscript to an ended relationship. Thus, he writes: “For everything that’s lovely is / But a brief, dreamy kind delight. / O never give the heart outright,” (6-8), followed by the final, ringing couplet of the poem: “He that made this knows all the cost, / For he gave all his heart and lost.” (13-14). The ending words, in that sense, show that Yeats hopes to save others from his own mistakes. In another lesson offered in the poem, Yeats cautions against being so devoted that your lover takes you for granted. Holding something back lends an air of mystery, allowing the relationship to breath and become stronger. Never give all the heart, for love Will hardly seem worth thinking of To passionate women if it seem Certain, and they never dream That it fades out from kiss to kiss; (1-5) Here Yeats seems to be saying that lovers who give their all to another have better odds for being taken for granted and, eventually, cast off. If doubt were kept part of the relationship, then, perhaps women would be uncertain, more intrigued, and less likely to feel their ardor fading “from kiss to kiss” (5). Whether we should adopt Yeats’ advice as a precept is a question left to individual readers. Clearly the sonnet was written while Yeats himself was in an emotional state and a bit bewildered and vulnerable. Nevertheless, his warning about life’s most celebrated “kind delight” – love – resounds through time for both readers who have experienced love and readers who have not. This powerful force, Yeats proves, is as worthy of our mind’s logic as it is our heart’s ardor. If you ignore your brain and don’t keep a part of your heart to yourself, you do so at your own risk.