A Study of Dispute Resolution Processes Between Teammates In

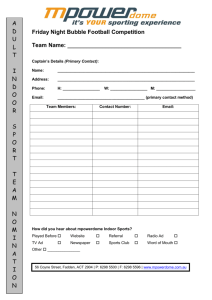

advertisement