Chords, Harmony & Chord Progression

advertisement

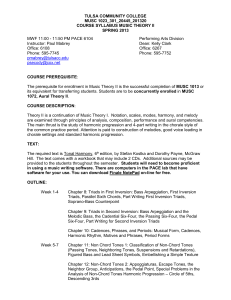

ICM L18: Chords, Harmony and Chord Progression Chords, Harmony & Chord Progression Introduction In order to talk about chord progression several terms and notations must be introduced. These terms are used to talk about music and analyse it. Just as it is not necessary to be aware of what is going on in these terms when you are listening to music, it is not necessary when writing music. However, it may be helpful in some cases. Analysis can be useful to the composer since it can allow them to get an idea of why certain things work and certain other things do not. It can enable them to get an idea of the working principles behind certain pieces of music, and so to create music that works upon those principles themselves. As such, analysis can help composers to extend their writing capabilities. This lecture contains material that goes up to grade 6 in music theory, and so you should not expect to get it all straight away. Don’t let the complexity put you off, it’s just being covered so that it is there for you to use should it prove useful in the future. Definition of a chord ‘A combination of three or more pitches sounded simultaneously.’ thefreedictionary.com Triads The above definition implies that a chord must be more than two notes. Two notes sounded together are just called an interval. A chord with three notes is called a triad. In each key the tonic triad is made up of the first, third and fifth notes of the scale. Each note of a major scale or minor scale has it’s own triad (of this form) of which it forms the root or bass note. The two remaining notes of the triad are each separated from the lower frequency note by one note that appears between them in the same diatonic1 scale, but which is not played. Since there are seven notes in a scale, there are seven of these triads. The number of tones each of these notes is separated by depends upon the root note of the triad. Figures 1 & 2, below, show these triads in the C Major and the C Sharp Major scales. 1 The term diatonic is used here to refer to the major scale and all forms of the minor scale. The strict use of the term diatonic means a mode or transportation of the white note scale; meaning that diatonic does not include the ascending minor scale, or the harmonic minor scale. However, in practice the term diatonic is often used to refer to the major and all forms of the minor scale. ICM L18: Chords, Harmony and Chord Progression Figure 1 (above). Seven triads in the C Major scale. Figure 2 (above). Seven triads in the C Sharp Major scale. Roman Numeral Notation Roman numerals I to VII (one to seven) are commonly used to talk about chord structures. These numerals are used to refer to the seven triads, above described, in each diatonic scale. It is useful in many instances to talk about these seven triads without talking about any particular scale, since the triads in each scale are, like the scales they relate to, just transpositions of each other. Figure 3, below, shows the triads for any major scale2, and notation and terms that are commonly used to describe these. 2 A different table (with different triads being marked as major or minor and so on) would be needed for each of the forms of the minor scale, since the notes within these scales have different relationships to one another (see ICM L6). ICM L18: Chords, Harmony and Chord Progression Roman I Numeral Degree Tonic of Scale ii Iii IV V vi vii Supertonic Mediant Subdomin ant Domi nant Submediant Leading Note Figure 3 (above). The triads for any major scale. Often in Roman numeral notation, upper case letters are used to indicate major triads and lower case minor triads. There are also symbols used to distinguish diminished triads (), and augmented triads (+). However, these formalisms and symbols are commonly dropped when they are not relevant to the analysis, leaving just the roman numerals, all given in capital letters irrespective of whether major or minor triads are being described. Major, Minor, Augmented and Diminished Triads Major triads all have this interval pattern: major third and then perfect fifth. Minor triads all have the pattern: minor third, perfect fifth. Diminished triads have the pattern: minor third, diminished fifth (6 semitones). Augmented triads have the pattern: major third augmented fifth (8 semitones). For example: C-E-G is the tonic triad in C major. It is a major triad. It starts from the root note has an interval of a major third (4 semitones) from C to E, and an interval of a minor third (3 semitones) from E to G. From C to G is a perfect fifth (7 semitones). The tonic triad in C Sharp Major is also a major triad as it has the same intervals between each note. major third minor third (4 semitones) (3 semitones) perfect fifth (7 semitones) major third minor third (4 semitones) (3 semitones) perfect fifth (7 semitones) Figure 4 (above). The intervals of the tonic triad in C Major (left) and in C Sharp Major (right). The intervals of all major triads are the same. ICM L18: Chords, Harmony and Chord Progression Inversions When the bass note (the lowest note) is not the root note the chord is inverted. All triads can be inverted in two ways3. With triads: the first inversion has the third note as the bass note and above it the fifth and the root; in the second inversion, the fifth note is the bass note. So, for example, figure 5 (below) shows the inversions of C-E-G the first inversion is E-G-C and the second inversion is G-C-E. Figure 5. C-E-G (above left) and its inversions: E-G-C (above) and G-C-E (left). To give a further example, figure 6 (below) shows the chord C-E-A. This is an inversion of A-C-E (see fig 6), and so is more closely related to A-C-E than it is to C-E-G (see fig 5). Figure 6. C-E-A (above left) is an inversion of A-C-E (above right). Use of Chords in Composition Pieces of music are very often based around a particular chord progression. Sometimes melodies (as well as bass parts) are written so that they fit into a particular chord structure. Sometimes a melody is written and then chords are found that go with it, lending further character to notes in the melody: this is called harmonisation. Joe Meek (60s record producer), for example, used to sing a melody and get a professional musician to suggest different sets of chords that could go with it. He would then choose the one he liked the best. 3 Chords with four notes can be inverted in three ways, chords with five notes, four ways, and so on. ICM L18: Chords, Harmony and Chord Progression Chord Progression Basic Chord Progression Moving from one chord to another is the most basic chord progression. Many well-known pieces of music are built upon the oscillation between two chords of the same scale. For example, Erik Satie's first Gymnopédie for piano and the Velvet Underground's Heroin are both built upon a repeated I – IV. With Satie’s first Gymnopédie, for instance, the first few bars feature an alternating progression of two major seventh chords4 in D major. The first on the subdominant (G-B-D-FSharp), and the second on the tonic (D-FSharp-ACSharp). Sub-dominant triad in D Major Added Seventh Tonic triad in D Added Seventh Major Figure 7. The first few bars of Satie’s first Gymnopédie feature chords based on the above. The actual piece uses a variation of these chords: in the chord on the right, the second note in the tonic triad is played one octave up (and so the actual chord here is a variation of the second inversion of the tonic triad); and the bass notes of both chords are played one octave down. Common Chord Progressions The chords I, IV & V cover all notes of scale and so can be used to harmonise any melody. These can be arranged in many orders, for example: I - IV - V – V I - I - IV – V I - IV - I - V I - IV - V - IV They can also be varied by adding sevenths, using inversions, and so on or by substituting relative minor (ii) for IV. I – ii- V (used in the Beach Boy’s Good Vibrations) Another way of varying them is to double the sequence in length, leaving the first half unresolved: 4 Seventh chords just have an added extra note a seventh above the root of the chord. ICM L18: Chords, Harmony and Chord Progression I - IV - V – V & then I - IV - V – I 12 bar Blues Progressions are elongated 3 line form of I- IV- V: I-I-I-I & IV - IV - I – I & V-V-I-I This blues progression can be varied in many ways: replacement of chord with fourth or fifth chord (dominant/subdominant) chromatic passing chords ii-V-I turnaround (turnarounds are often used at the end of a section before the music repeats) chord alterations: minors, diminished sevenths etc. I-IV-V can also be extended by adding in a sixth chord (these are known as 50s chord progressions): I – vi – IV – V or I – vi – ii – V Another chord progression is the circle progression. This is based on moving between notes that are closely related harmonically by moving up a fourth each time (going back to I after vii). I - IV - vii - iii - vi - ii - V - I The above progression can be varied, for example, by substituting major for minor chords.