Regional Dimensions of Capacity Building for Municipal

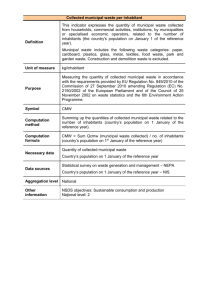

advertisement

Regional Dimensions of Capacity Building for Municipal Governments: Experiences and Lessons learned from Eastern and Southern Africa By George Matovu Regional Director, Municipal Development Partnership, Eastern and Southern Africa Reference paper during the LORC Symposium on developing a System for Local Human Resource Empowerment and Local Policy Making from October12-14, 2003 This is a draft working paper designed to contribute to discussions on issues of capacity building for local government in Africa. It is hoped that the final version will benefit from the insights of local government practitioners in the region and beyond. Introduction The challenges facing municipal governments within the context of capacity building1 can be guided by the following factors: How the competencies of local governments can be improved to better deliver services, alleviate urban poverty, create jobs, promote peace and security, prevent spread of HIV/AIDS, and foster sustainable development; The conditions under which municipal government officials should be expected to demonstrate accountability and transparency. The kind of capacity building programs that respond to the needs of municipal governments and need to be developed. The kind of institutions that should be involved in delivering such programs and who should be targeted; and How municipal governments be encouraged to take advantage of capacity building when it is available to effectively participate in the implementation of the New Partnership for Africa Development (NEPAD). From the World Bank perspective cities and towns are considered functional when they are: (a) livable, that is, they must ensure a decent quality of life and equitable opportunity for all residents; (b) productive and “competitive”; (c) well governed and managed; and (d) financially sustainable, or bankable. Another complementary perspective is that cities and towns should be: (a) inclusive (politically right and sensitive; (b) credit worthy (books of accounts should be clean); and (c) efficient (in delivery of services). When African cities and towns are measured against these factors, they live a lot to be desired. They are known for being overcrowded, with unplanned settlements, huge piles of rubbish and filth, high levels of unemployment, run-down infrastructure, poor services, to mention a few. Peter Morgan (1999: 14).described capacity building as “involves identifying the constraints and helping those need to improve their ability to carry out certain functions or achieve certain objectives” 1 1 However, on the other hand, African municipalities are centers of opportunities. They are the growth centres that serve as incubators of local entrepreneurs, and provide the incentives for transforming and modernizing societies. This paper presents an overview of the regional perspectives on capacity building for urban local governments that have emerged over the past two decades based on the challenges and opportunities of the time. The paper draws on the experience of MDP as a continental institution mandated to promote decentralisation and enhance capacity building for decentralised urban local authorities. It is hoped the presentation will provoke thoughts and discussions that will add value to the design and implementation of Africa Local Governance Program in the participating countries – Mozambique, Tanzania in East Africa, and Ghana and Mali in West Africa. The paper is organised as follows. Following this introduction, the paper gives a brief overview of the current state of affairs in urban areas. This is followed by a brief outlay of what constitutes capacity building. The next outlines the various perspectives and ideas that have dominated capacity building over the last two decades. The paper concludes with an opinion expressed by Col. Ngandwe the former president of the International Union of Local Authorities (IULA) and former Mayor of Kabwe Municipal Council in Zambia. Situational Analysis Poverty: One of the major challenges facing most central and local governments Africa is poverty, which manifests itself in different ways. It is estimated that 340 million people, or half the Africa’s population, live on less than US $ 1 per day. The mortality rate of children under five years of age is 140 per 1000, and life expectancy at birth is only 54 years. In Africa, rural poverty is more often recognised and addressed. This is not the case with urban poverty, which is often less recognised. There is a presumption that those living in cities will automatically better access to services. Woefully for the majority of urban dwellers, this is not necessarily so. Many live in abject poverty and are often far worse off than their rural counterparts. As rightly observed by Richard Stren (2001), there are very strong reason why government must fight poverty. He points out that: Poor people cannot pay taxes or support public services without substantial levels of government funding; The very poor cannot contribute in a productive manner to the development of a pool of skilled human resources necessary to generate goods and services in the modern competitive economy; and The poor cannot easily participate in community activities in order to provide facilities and organisational structures at the neighbourhood level. It is important to note however that effort are already underway in several Africa countries to address poverty, with a deliberate shift to urban poverty. For example, the strategic goals for local development in Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda, as set out in their respective PRSPs are in line with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). In Ethiopia the targets for poverty reduction set out in the PRSP are: (i) a reduction in income poverty by about half by 2015, and from 44% in 1999/2000 to 40% in 2004/05; (ii) a reduction in infant mortality from 97 per thousand in 1999/2000 to 85 per thousand by 2004/05; and (iii) an increase in the gross primary school enrolment rate from 57% in 2000/01 to 65% by 2004/05 (Government of Ethiopia, 2000). In Kenya, the poverty reduction strategy comprises five elements namely: (a) to facilitate sustained, 2 rapid economic growth;(b) to improve governance and security; (c) to increase the ability of the poor to raise their incomes; (d) improve the quality of life of the poor; and (e) to improve equity and participation (Government of Kenya, 2000). Unfortunately, going by current statistics, it is increasingly becoming clear that halving poverty by 2015 - whether at global or national level cannot be achieved. At the 2003 Spring Meeting of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, the World Bank made it clear that an annual sum of US$ 100 billion was required to attain this goal (Eckhard Deutscher 2003 in Development and Co-operation Vol. 30, No. 8/9, p. 336). HIV/AIDS: This situation is being exacerbated by the prevalence of the HIV / AIDS pandemic. Sub-Saharan Africa is by far the region most affected by HIV / AIDS in the world. The region which inhabits only 10% of the world’s population, accounts for 70% of the people living with HIV/AIDS worldwide, 83% of the deaths related to AIDS, and 95% of the orphans due to AIDS (UNAIDS 2002). The prevalence of HIV/AIDS is very high in countries such as Botswana, Swaziland and Zimbabwe where more than 30% of their adult population are living with HIV / AIDS. The impact of HIV/AIDS on central and local systems is daunting. The epidemic has: (a) increased the demand on the health care systems, (b) reduced life expectancy to 38 years and increased infant mortality, (c) reduced the ability of citizens to pay for services and taxes, (d) threatened productivity due to absenteeism and loss of skills, and (e) increased the number of orphans and child headed households. Sectarianism and elitism: There is apparent sectarianism and elitism on the part of the urban area politicians and administrators. In 400 BC, Plato (as cited by Molly O’Meara 2001: 337) observed that “any city, however small, is in fact divided into two, one the city of the poor, the other the city of the rich”. This observation is still as valid as it was in 400 BC. In the African context this divide is no exception. There is a pervasive perception of “us and them”. Most top city administrators in urban areas seem to regard the urban poor largely as aliens in the urban areas who should return to the rural areas to till the land. Most often they seem to forget that the urban areas equally belong to these administrators as it does to the urban poor. At the same time, due to lack of nationalism on the part of both the administrators, politicians and urban citizens there is also an apparent lack of belonging and commitment to long term solution to urban poverty and unemployment. In Kampala for example, many administrators and urban dwellers have their original home areas where they individually dream of returning when things in the city really go bad. This creates less of a spirit of togetherness and well-being of the city such as concern with cleanliness. Infrastructure: Most urban authorities in Urban Sub-Sahara Africa are having difficulties building and maintaining their infrastructure partly due to the high cost of imported inputs. In many places, the infrastructure that was left behind by the colonial masters has crumbled without building news ones. It is generally accepted however that the deteriorating terms of trade against primary exports and massive devaluations and exchange rate depreciations in structurally adjusting countries has had a negative impact on the municipalities’ ability to construct and maintain their infrastructure. Poor governance: Whereas it is true that municipalities lack financial, human and physical capacity, several questions have been raised about the styles of governance and management in many African cities. For example, in 2000 Arsene Balihuta asked; “…why is it that during the colonial era urban governments were able to build and maintain more infrastructure when they had relatively less real resources than their counterparts today”? He attributed this to current city fathers and managers who are probably less visionary, more corrupt, less efficient and less altruistic than those during the colonial era. 3 Lack of capacity: Not withstanding the above question, there is no doubt that most of urban areas south of the Sahara, apparently lack of financial, human and physical capacity. Cities usually get grants and money from property, sales and income taxes. In theory, this means that, other things remaining constant, the wealthier the city community and the more productive and higher the level of economic activities, the higher the amount of financial resources that will be available to the city administration. Outside South Africa, none of these conditions appear to be true for SubSaharan Africa. Council administrations in various countries have less money with which to attract skilled workers and administrators, acquire equipment for building and maintain their physical infrastructure, and construct buildings for their Councils. Evolution of Governance: Governments in Sub-Saharan Africa are undergoing a process of political, functional and fiscal decentralisation and democratisation. Through this process, regional and municipal governments have gained increased importance in provision of basic urban services as well as promotion of local development. The process of democratic decentralisation is taking place at a time when the Africa region is urbanizing at one of the most rapid rates in the world. Unfortunately however, the capacity to plan, manage and administer has been overwhelmed by the rapid population growth which is rated at an average if 5 per cent. Urban planners and managers have not been able to react well to this growth. The interrelatedness of the problems is so complex that conventional methods and traditional solutions can no longer work. Management of cities is often made more difficult by speculative practices especially in land management, poor information, lack of foreign currency, inadequate human resources capacity, and discriminatory practices associated with gender, ethnicity, race religion, or social status. A combination of poverty, bad governance, poverty, poor infrastructure have come together to undermine capacity building and lack of it. In deed, it has become a significant barrier to Africa’s economic growth preventing the continent from tapping into global opportunities, resources, and technological advancements and thus, compounding the poverty cycle and underdevelopment even further. What is Nepad? Essentially, Nepad is a commitment by developed nations (primarily the West) to assist African nations to get out of the economic and governance crisis they are in and develop to comparable levels. In turn, African nations have to commit themselves to change their ways and attitudes towards economic management and governance. What does Capacity Building constitute? It includes creating an enabling environment by providing the necessary tools for the job. Capacity building is more than just improving the skills and competencies of those involved in providing services. In 1991, Professor Akin Mobugunje pointed out that “…to spend substantial sums of money training officials only for them to come back to find that they cannot operate effectively because the local government has no working vehicle or telephone, or typewriter can seriously undermine morale”. It requires a clear and shared vision, unity of purpose and goals, and aspirations by stakeholders and proper planning to attain the stated goals. Deborah Eade (2001) pointed that “It does not help to train individuals when organisational vision is unclear, organisational culture is unhelpful, and structure is confusing or obtuse. It does not help to secure resources when the organisation is not equipped to carry out its tasks. It does not help to develop information 4 management systems when the basic organisational attitude is one which rejects learning through monitoring and evaluation in favor of frantic activity”. It requires to remove obstacles and dealing with negative attitudes and behavior fostered enhanced by outdated laws and regulations. In 1999, Kim Forss and Pelenomi Venson pointed out that …capacity building is subject to a variety of interpretations. “Capacity building is not necessarily growth and expansion. It is also about removing obstacles (such as outdated bye-laws) and altering processes and approaches”. It requires positive incentives to minimise institutional failures. Institutional failures in urban service delivery are not only the result of a lack of technical knowledge on the part of local government staff, but also reflect constraints and perverse incentives confronting local personnel and their political leadership. These in turn are often caused by problems in the relationship between central and local governments. [Source: The World Bank Better Urban Services: Finding the Right Incentives (Washington, DC: 1995).] Regional Perspectives on Capacity Building Over the past two decades, a wide range of approaches to capacity building for African urban local governments has been discussed and experimented. Perceptions on capacity building and areas of emphases have varied from year to year depending on the challenges of the day as well as the preferences of those supporting the process. In the following section, an attempt is made to outline some of the perspectives and ideas that have dominated capacity building in the last two decades. Institution Capacity Building was considered critical to galvanizing transformations: When African countries were obliged to embark on economic structural adjustment programs in the early and mid-1980s, the focus was on ‘institution capacity building’ or ‘strengthening’. As a matter of urgency, this required reviewing and adjusting internal organisational structures (organisational re-engineering), systems, strategy and skills of individual organisation mainly in the public sector. The emphasis was on lean and flat (economy) organisations. The rationale was that once the organisational structures are right, performance would naturally follow. The second aspect of re-engineering was the rehabilitation of institutions such as universities, hospitals, roads, or building new facilities all together. Such interventions tended to be supply-driven, and donor-driven and expatriate-driven. Use of young expatriates and aid workers was introduced as a cheap strategy and mechanism for establishing required capacity in place: The initial attempt towards building capacity for local management involved bringing in young expatriates who were expected to transfer responsibilities and competencies to nationals. Local nationals were expected to understudy their counterparts and eventually take over when the expatriate left. What was achieved? Not much. The reality was that transferring skills and knowledge encountered resistance from nationals who felt that they new much more than the young expatriate. As a result, performance in infrastructure and service provision remained poor and far from reaching people especially the urban poor. Scholarship were provided to enable young professionals to study abroad to acquire not only knowledge but also the right attitudes and work culture: As a matter of evidence, there was no guarantee that this approach would produce the kind capacity needed to address the emerging critical issues. Many beneficiaries of scholarships did not return to their countries leading to further loss of capacity for national institutions. Secondly, the retention capacity of institutions utilizing trained cadres especially the public service became weak because of low level of salaries 5 and bad working conditions. Many well-qualified individuals resign from the civil service to join either the NGO sector or the private sector. The institutional capacity building was welcome but had clear flaws: The institutional development approach was criticised on a number of fronts for failing to address the widespread malaise in all public offices characterised by incidents of laziness, abstention, corruption, rudeness and lack of courtesy to members of the public. At the local levels, there the following flaws were observed. For example, in 2001 Mila Freire pointed out that in order to achieve sustainable urban development in infrastructure and service provision, it was imperative first, to have a more integrated approach across the physical environment, infrastructure net works, finance and institutional and social activities and secondly to link capacity building to the issues of governance. There were further observations. For example, first there was no meaningful beneficiary or community participation in decision making even where their lives were directly affected. There was no appreciation of corporate governance based on a shared vision, values and principles transparency, accountability, honesty and integrity. At the national level in particular, government departments were not sufficiently prepared to take lead in promoting public administration reforms. To begin with, there was an acute shortage of skilled and well motivated manpower to manage the rehabilitated or newly established institutions. Besides, the capacity for sector policy analysis and development, project design, management, monitoring and evaluation was also not available. Many governments responded by importing expatriates from all over the world mainly from their former colonial masters. Wide spread poverty and the social costs of economic structural adjustment forced governments and donors to review capacity of institutions to alleviate poverty: The first generation of structural adjustment programs that were implemented without a “human face” did not only make the poor poorer but they also created a significant group of the new poor. In 1992, the growing concern about the increasing poverty and the social costs of economic structural adjustment forced central governments and donor agencies to start talking about an African regional training program focusing, but not limited to, on (a) the design and management of poverty alleviation programs and projects (b) systematic analysis of issues related to poverty, and (c) facilitating exchange of experiences and innovative practices on how individual local authorities are addressing the issue of poverty and its manifestations – crime and violence, corruption in official transactions, prostitution, street children etc. There was a deliberate effort to strengthen the capacity of central and local government and NGOs to formulate and implement policies, sector programs and projects which would contribute to sustained reduction of poverty while promoting and strengthening the participation of the poor and vulnerable groups in activities which would improve their standard of living. Decentralisation and democratisation was considered to be an effective tool for building capacity for good governance and promoting quality of life of the urban poor: Towards the end of 1980s, there was a clear policy shift which (a) promoted decentralising/devolving powers and responsibilities to local government, (b) called for establishment of good governance with emphasis on accountability, transparency, and integrity; (c) promoted democratic governance; (d) called for meaningful community participation and the principle of subsidiarity, and (e) for creating space for involvement of non-state actors (from civil society, NGO sector and private sector) in municipal governance, local development, and delivery of services; (f) emphasized capacity building for capacity building. Capacity building for implementing economic reforms, decentralisation and democratisation programs brought to the fore several issues which have shaped approaches to capacity building in local government. For example, it emerged that decentralisation is a multi-faceted complex 6 political process even when it was confined to one sector or agency, as was often the case. In that regard, it required a multi-sectoral approach, which in turn require intensive coordination of various government ministries or departments. It became a complex process because it did not involve only one aspect public administration. It involved political, fiscal, and administrative changes. It in varying degrees took on different forms including devolution, deconcentration, delegation or privatization of services of government. It called for active participation of citizens who in turn became more aware of their rights with sophisticated needs and demands. Decentralisation is complex not only because of the form but also the different and conflicting interests that are involved in the debate and operationalization. The different interests include; reform minded politicians and operatives, conservative traditionalists, donors, and recipients of the benefits of decentralization. Consequently, the implementation of decentralisation policies requires, amongst others, the following consideration. First, a sound institutional architecture that is culturally and politically sensitive and allows for detailed planning and coordination. Secondly, human resources base that understands the demands and complexity of the challenges. A capacity building approach that is capable of accommodating the complexity of views and interests. The above considerations require a needs assessment program that is not only be technically sound but also balanced and sensitive. Our experience is many capacity building program have not achieved the desired results because they are viewed with suspicion hostility and seen as a waste of resources. Addressing attitudes and behaviors was considered critical in moving decentralisation forward: As decentralisation unfolded, it became clear that there was urgent need to pay attention to attitudinal and behavioral aspects at various levels. Even where policies were clear and guidelines were getting in place in a countries like Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, both elected and appointed officials, as well as the active citizenry reacted in different ways. For example at central level, government officials particularly from sector ministries such as education, health, works, environment were accustomed to making policy decisions and passing them over to local authorities for implementation. In that regard, central officials resisted decentralisation because of the fear to loose power, influence, as well as personal gains emanating from touring their areas of jurisdiction. There was a perception that decentralisation would erode the power, authority, and legitimacy of senior officials. Junior officials on the other hand, resists decentralisation because they hated being posted to field offices. The transfer to a field office was perceived to be a demotion or as a cut out from opportunities of personal benefits associated with being at headquarters. The problem attitude was highlighted almost by all ministers at the 1999 Ministers conference that took place in Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe. Minister Jaberi Bidandi Ssali from Uganda, said, …that there was need to generate adequate attitudinal change among central bureaucrats to give the decentralisation programme unquestioned commitment and support2. Minister Kingunge Ngombale-Mwiru of Tanzania put it thus; “Devolution of powers and resources to local government authorities in essence means taking away the same from Government ministries and institutions, which is in itself a big challenge. No ministry or centralised institution will willingly give up power and resources. In order for decentralisation to succeed, serious sensitisation of the entire political leadership should be undertaken, and a common vision of the model of decentralisation should be agreed upon and guided by law. The community should also be sensitised and mobilised so that they understand the 2 See paper presented by Minister Bidandi Ssali 7 benefits which go with decentralisation and empowerment, so that they will own and cherish the process”3. There were also behavioral issues that need attention. For example, in many countries particularly in Eastern Africa, local officials were (and still are) not accustomed to being accountable to local residents. In Southern Africa, local people were not used to paying for public services and had the mentality that development ideas and projects came from government. As Richard Bird once pointed out (2001: p. 171), to many people the very idea of charging for public services seems rediculous. Capacity building was called for to address such long-held attitudes and behaviour patterns as strategy to bring about the desired change. Establish honest behaviour and government is key to sustainable capacity building: The other major component of capacity building that had been omitted until the 1990s was the need to develop local integrity systems to fight corruption (the misuse of public power for private profit) at municipal level. As Col. Ngandwe rightly points out (2003: p. 12), no amount of resources or effort can yield sustainable development and satisfactory service delivery in the absence of local integrity systems which prevent the scourge of corruption. Economic hardships that public servants experienced as a result of structural adjustment programs resulted in unprecedented corruption that adversely affected the capacity of central and local authorities to deliver services. Decline in various aspects of integrity at various levels of governance significantly started undermining the process of decentralisation, democratisation, institutionalisation of good governance and overall socio-economic development. Studies in Eastern and Southern Africa revealed however small the level of corruption, the practices resulted in inducing wrong decisions and projects, unqualified individuals being awarded contracts, delivery of sub-standard services and ultimately erosion of public confidence in public service and formal institutions. It was against this background that MDP introduced programs for, among others, (i) raising awareness of the effects of corruption with regard to services delivery; (ii) promoting service delivery surveys to seek citizen opinions (satisfaction / dissatisfaction) of citizens regarding corrupt tendencies in their local authorities and to set benchmarks against which the progress in fighting corruption can be measured; (iii) empowering the various pillars of local government integrity through workshops and seminars; (iv) developing leadership codes of conduct; (v) developing clear public procurement processes which are understandable, transparent, open, competitive, and fair; and (vi) promote development of charters for building integrity. Broadening participation in municipal governance enhances the capacity of municipal governance to incorporate the demand side in decision making: As Dele Olowu (2001) points out, decentralisation does not imply only the vertical transfer of responsibilities and resources from central to local governments (conventional conception of democratic or devolutionary decentralisation), but also the development of horizontal networks between various sectors and between sectors and local non-state actors (the private sector, civil society, and international organisations). Capacity building from this perspective is needed to improve coordination and consultation. Given the complexity of urban issues, it is vital to promote a multi-disciplinary approach to capacity building for sustainable urban development: Specialized training in fields like engineering, law, medicine, and economics will continue to be an important way of providing a human resource base for development. However, experience across the region show that the 3 See paper presented by Minister Kingunge Ngombale-Mwiru of Tanzania. Also see the paper presented by Dr. Dele Olowu 8 current professionals are so compartmentalized to the extent the they are not able to deal effectively with complex problems such as poverty, corruption, and HIV/AIDS. In 1996, Richard Stren expressed more or less a similar perspective when he pointed out that “… city management has to be studied from a variety of angles and disciplines”. Stren went on to say that, “Today, solutions to problems at the local level, as ell as urban success in the global environment, require a non-ideological and multi-sectoral approach as well as popular participation in decisions making. In light of this backdrop, it would be helpful if capacity building programs are capable of promoting a multi-disciplinary, multi-sectoral approach to city / municipal development and management. Promoting civic participation in municipal governance means promoting productive working relations between those who govern and those who are governed: At the end of the 1990s, more attention was given to strengthening civic participation in municipal governance when it became increasingly clear that municipal governments were failing to deliver services and needed support from the civil society. There emerged a genuine need to strengthen the capacities of both civil society and local governments to work together more productively to design and implement development programs. Civic participation was viewed to be an effective vehicle to shift decision making from top-bottom approach to bottom-up approach and for enhancing (i) efficiency and effectiveness in allocation of resources and delivery of municipal services; (ii) the establishment of cost-sharing arrangement; (iii) empowering local communities; (iv) sustainability of benefits; (v) accountability and; (v) poverty reduction and equity. Community capacity building would include areas such as understanding of how municipal governments operate (Plummer, 1999), participatory planning and budgeting, the rights, obligations and responsibilities of a citizen. On the other hand, municipal officials would need skills (political, administrative, community relations) to better manage and facilitate the involvement of non-state actors in local governance. Private Sector involvement is needed to enhance efficiency in service delivery: The reforms in public administration in the 1980s brought in the role of the private sector. Local governments particularly the urban ones, came under pressure to create space for the involvement of the private sector in service delivery as a reaction to accusations of inefficiency and corruption in public institutions. Local authorities also came under pressure to start running their institutions on business principles without compromising their social obligations, as well as equity and electoral considerations. In some measure, local governments were required to begin to view their resident or voters as their customers or clients and to treat them in a more responsive fashion (Mila Freire and Richard Stren 2001: 194). As Richard Stren points out, fundamental changes were undertake. Executive mayors, directly elected by the urban citizens came into existence and assumed the new title of city managers. Town clerks were placed on contractual terms and came be known and municipal directors (Tanzania), chief executive officers (Malawi), or urban managers (South Africa). With these changes, local managers needed to be capacitated to know how to, among others, establish an enabling environment and conditions for private sector involvement, become enablers rather than controllers, regulate competition, promote fair public-private partnerships, apply negotiation skills, handle tendering and contracting, prepare feasibility studies, prepare and manage service contracts, pricing and administer cost recovery, handle labour issues, environmental management, evaluate performance etc. Understanding Central-Local Relations is a necessary condition for enhancing municipal capacity to undertake the decentralised functions: There is also the issue of central-local relations. The central problem here is the understanding and appreciation of the institutional and legal frameworks governing the relations between the central and sub-national levels of governance. In Zimbabwe for example, local government is a legislative rather than a 9 constitutional creature while in Uganda and South Africa, local government is provided for in the constitution. In the case of Zimbabwe, local government has no independent constitutional existence. One can safely say that it is an appendage of central government whose birth, development and death is almost entirely in the hands of central government. As Eldred Masunungure (2003) rightly advocates, something urgently needs to be done about central-local relations to improve local governance. Building and Improving Municipal Financial Capacity is key to successful democratic decentralisation: It has now been established that central to any successful scheme of decentralization is a sound fiscal decentralisation policy and a sustainable system of intergovernmental fiscal transfers from the centre to regional and local jurisdictions as well as allocation of expenditure responsibilities and authority to raise local revenues. The design of the system of transfers can make an important contribution to efficiency, equity, poverty alleviation, accountability and the consolidation of democratic forms of government. Local governments need to be capacitated to put in place sound financial management particularly in handling revenue sources and expenditures. The following conditions, amongst others, should be met: Clear and internally consistent systems of local revenues and expenditure Transparent and predictable intergovernmental transfers Prudent conditions for municipal borrowing Generally accepted financial accounting practices Sound asset management process (an accurate register for all assets; maintenance processes to keep assets in good condition Transparent procurement practices Improving level of tax effort and administration, efficiency in collection of revenue, updating cadastres and roster of service users, reforming poorly designed local revenue-generation strategies and ensuring progressive system with appropriate instruments are some of the areas capacity building is advocated. In spite of the extent and speed of decentralisation, and the growing volumes of resources available to local governments throughout Eastern and Southern Africa, the issue of intergovernmental fiscal relationships has not been sufficiently analyzed, and debated. This represents a major shortcoming in the process of decentralisation, and a potential obstacle to a successful delegation and/or devolution of responsibility and authority. Civic education is a significant input to empowering citizens and an effect way of counteracting the culture of socio-political apathy: Capacity building for community mobilisation and participation has come under spotlight as a significant strategy for enhancing good governance and legitimacy of local authorities. Apathetic response to the local government activities such elections broadened the debate on capacity building. Apathy by definition is reluctance by citizens to participate or in the case of elections, electing not to vote or to stay away. In principle, apathy is manifested in attitudes of despair and depression created by political circumstances, non-involvement of people in important issues that affect their societies, lack of interest in public affairs, an attitude of resignation, withdrawal and despair and a state of hopelessness. Apathy is caused by a number of factors that include imposed leaders, corruption, destructive power struggles, unfulfilled promises, just to mention a few. In the midst of dynamic transformation, there is need advocacy for civic education to develop capacities and potential among citizens on democratic challenges and opportunities, as well as the need to appreciate issues of decentralised cooperation and coordination of local initiatives, power, governance, and 10 development. The other aspect of civic education that has been called for in recent years is voter education. This is a branch capacity building that focuses on preparation of citizens to participate in a responsible manner in the governance of their communities. Every individual no matter whatever level need to be capacitated to better address challenges facing municipal government: Beneficiaries of capacity building for improving municipal performance are many and varied. They can be grouped in the following categories: Councillors and Mayors: Councillors are key actors in democratized local government. They represent the citizens and are supposed to provide political leadership, have an appreciable level of civic knowledge with ability to manage public affairs. However, until late 1980s, it was never conceived that representation of ordinary people require a councilor to have extraordinary skills (Allen Hubert 1990, p.80). Moreover, their engagement was on a part time basis. Experience has proved that many elected councilors come to local authorities without prior management skills or knowledge of local government systems. A region-wide consultation to establish the capacity building needs of newly elected mayors revealed that mayors are interested in leaning about: how to engage residents in municipal affairs meaningfully, how to improve the resource base for their local authority, how to prepare strategic plans, how to attract investors, how to establish enabling policy and institutional environments, how to guard against corruption, how to handle street vendors, how to engage the private sector, how to commercialise or set rates for municipal services, how to play a meaningful role in preventing the spread of HIV/AIDS and how to respond to the needs of AIDS victims, how to protect the environment, how to protect children and women against abuse and violence, and to deal with street children. Chief Officers: While a number of professional training programs have been offered for technical staff like finance officers, engineers, planners, etc, it is assumed that skills in fostering participation and transparency would be acquired as one rises through ranks or by observing and learning from the practical experience of older members of staff (Allen Hubert 1990, p.80). There is need to equip mangers with formal knowledge, skills and attributes that are crucial for the effective good governance. Citizens: Citizens’ participation, especially the poor, in local government affairs is essential if local governments are to be held accountable for their actions and transparent in transacting business. By participating in decision making and planning processes, demanding quality services, and holding local officials accountable, citizens can ensure that government truly represent their interests. In order to foster community participation in local government affairs, there is need to promote civic education and community awareness programmes. Citizens need to be made aware of their rights and responsibilities to demand, participate in and monitor delivery of services to their community. They must be made aware of the cost of infrastructure, social services, and of the need for mobilisation of resources including taxation for delivery of the services. They need to be trained in participatory processes such as planning and budgeting, implementation and monitoring. They must also be conscious of the accountability of the elected and appointed officials to them, and their role in ensuring the integrity of their representatives. Community Leaders: Community leaders also need appropriate training to enable them foster citizens’ participation around issues of concern to them. Community leaders need to develop knowledge about power relationships (who controls, where do the funds come from, roles and responsibilities of citizens etc) and about financial mechanisms for services delivery. They also need to learn how to collect information and present facts, how to prepare projects, how to 11 mobilize the community to demand services and participate in their implementation, how to influence change in policy, programmes and services. Ministers and Top Officials: Ministers, top public officials and policy advisors of central government ministries responsible for and / or involved with local government also need to training. Whilst central government officials still control various resources, that lack adequate skills and mechanisms for consultation with local authorities. There is need to develop skills in consultation process to facilitate effective policy development. Ministers need to be exposed to ideas and exchange of views on current central/local government policy issues so that they may appreciate the role of local government in development and promoting good governance. Local government associations: Local government associations bring together those who work in local government to share information and experiences, build support network, initiate policy dialogue, present a common voice for local government on policy and management issues. Strong national associations can play an important role by identifying the needs of their members and could constitute a source of information on good local government practices. In order for national associations to play their advocacy role effectively, they need to know how to collect information and present facts, how to prepare policy positions and projects and mobilize their members to influence change in policy, programmes, and services. Professional Associations: Formation of professional Associations is also considered to be an effective way of building local government capacity. Example are abound across the region. These include for example the Namibia Association of Local Authority Officers (NALAO), the Kenya Association of Chief Executive Officers (KACEO), the Town Clerks Forum of Zimbabwe (TFZ), the Zimbabwe Institute of Planners (ZIMIP). Donors and Development Partners: There is growing concern the development partners come with preconceived ideas and objectives which contradict national aspirations. There is concern that central governments are bypassed and partners initiate unsustainable projects at local level. When such projects fail, both locals and government are blamed that they are incapable of understanding their own development needs nor sustaining them. There is need to develop the partner’s capacities for them to better understand and appreciate local values and intelligence to avoid white elephants. Research and Consultation: The experience of MDP since its launching is that one of the major impediments to effective decentralisation and effective service delivery in municipalities is the absence of action based research that can inform policy analysis and formulation as well as monitoring and evaluation of impact. The research should emphasise a multidisciplinary approach as well as participation of policy makers and beneficiaries to ensure ownership and maximum utilisation of findings and recommendations. The current MDP agenda supported by the Government of the Netherlands seeks to promote strengthening the capacity of urban local governments for service delivery and poverty reduction. Besides, a two year study on access to land by the urban poor for urban agriculture funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) is underway with a view to assisting urban local governments incorporate urban agriculture in urban policy making, planning and management. Perspectives on Training Institutions and Trainers 12 Training Institutions and Trainers lacked adequate orientation to effectively participate in strengthening the capacity of urban local governments: The development of capacity for capacity building seems to have come in as an after thought in the mid 1980s. It was realized that capacity building institutions – management institutes, universities, and research institutions were not in tune with local government reforms. The situation was made worse by absence of national training policies for reforming local governments. Historically, professional training that directly benefits urban local government in Africa has remained compartmentalized and in many ways disconnected from the realities on ground: What is available in some countries like South Africa and Zimbabwe are well trained professionals in fields such as engineering, planning, architecture, finance, medicine etc. but who lack adequate orientation to local or municipal government. This is, it is assumed that orientation towards local or municipal government would be acquired as one rises through ranks or “by observing and learning from the practical experience of older members of staff” (Allen Hubert 1990, p.80). Local governance is an art and a science. However very few training institutions in the region have any qualification focusing on local government. There are very trainers who can claim to have a clear appreciation of capacity building needs for management and development of cities. As Erwin Schwella (1990) observed that whilst conventional educational and professional training institutions in Africa are doing the best they can to close gaps in performance, training programmes in conventional schools and institutes of public administration and management are not dynamic given the tremendous training needs. Most of the courses are academic in their content and methods and do not reflect the realities on ground. Besides, the trainers are not well vast with participatory techniques, such as simulation, role playing, case studies which are taken for granted in private sector management training. There are hardly training institutions have gone beyond the emphasis on “professional” training to look at training as a broader concept that must examine controversial areas as ethics, integrity, transparency, and corruption: If training for accountability, transparency, and participation is to gain importance, it will require to review current training curricular and programmes, undertake needs assessment, design tailor-made interventions, and create appropriate institutional arrangements for delivering such programmes. Most of the training programmes are supply-driven: In most institutions, there is no effort to involve client organizations in training needs assessment nor are there resources to enable training institutions undertake post-training evaluation to get some ideas about the impact of their training programmes on the client organization. Many training institutions lack relevancy to their constituencies: Training institutions experience: high rates of staff turn over caused by poor terms of service for faculty staff and as a result high vacancy rate; inadequate funding for training programmes and support services; lack of locally developed training materials; and inappropriate facilities for level of programmes undertaken. Lessons learnt 13 Capacity building needs to localised: As pointed out by Tomasz Sudra (1995) of UNHABITAT, notwithstanding their weaknesses and shortcomings, national and local institutions, if facilitated, can adequately provide capacity building at sufficiently large scale and with required continuity. They have the vantage position to respond to the national and local needs taking into account the cultural context and the socio-economic economic environment. National association of local government: The existence of a national association of local government which is supported by the central government and with paid up members is helpful to capacity building institutions especially in identifying training needs as well as designing and delivering training programmes that respond to local needs. Reference and advising municipalities: Municipal authorities themselves should play a central role in enhancing the capacity of the local government fraternity through decentralised cooperation and direct mentoring. MDP has identified several types of municipalities, each with a unique history and at a different stage of institutional, political, and financial development. Resource municipalities are those in Africa and around the world that have developed sectoral expertise, and tools as well as acknowledge successful practice, and willingness to share their experience with others. (Bulawayo, Zimbabwe; Jinja, Uganda; Windhoek, Namibia; Ilala, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; Porto Alegre, Brazil). The strategy involves promoting transfer of skills, technical exchange visits and twinning, internships and apprenticeships for young professionals. Reforming/transforming municipalities are willing to exchange ideas, learn from others, and take action to transform municipal government to be more efficient, transparent, and equitable providers of services. (Nairobi, Kenya; Kampala, Uganda; Blantyre, Malawi; Gweru, Zimbabwe). For reforming municipalities the program involves promoting pilot programs for testing new approaches, such as introducing local integrity systems, performance management systems, integrated strategic planning, participatory budgeting, and gender and poverty assessments. Uninformed municipalities in the past had limited information and exposure to new ideas but are undefined to take action. Uninformed municipalities are reached through dissemination of good practices via printed material, audio-visual aids, participation in regional and national work-shops, and low cost study visits to nearby reference municipalities. Sceptical municipalities have information but are not prepared to take bold steps to undertake reforms. These municipalities are generally unsure of the implications of reform. Sceptical municipalities reached through advocacy programs organised by AULA. Since 1998 MDP made explicit strategy to support reform-minded municipal governments with a view to use their capacity to strengthen the capacity of those municipalities with expressed needs. Areas that have attracted a lot of interest include solid waste management, commercialisation of municipal services, establishing local integrity systems, participatory budgeting, strategic planning, and information management. Using modern technology to revolutionalise capacity building: The MDP Africa Local Government Action Forum (ALGAF) supported by the global distance learning technology of the World Bank and the digital radio have resulted into expanded outreach for capacity building in local government. The opportunity to access distance learning centres in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, 14 Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Zimbabwe has enabled MDP to reach over 1000 participants within a space of two years. Besides, the digital radio program that has been piloted in Malawi to take care of the small rural municipalities who do not have access to distance learning facilities has further extended the frontier for capacity building. Through the DL Centres MDP has been able to organize the following courses. In addition to ALGAF, other interventions undertaken in collaboration with the World Bank Institute include: Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations and Local Finance, Urban and City Management Municipal Anti Corruption, and Local Economic Development. Conclusion I will conclude by quoting what Col. Max Ngandwe said. For effective local government based on democratic decentralisation to succeed, there is need for capacity building in its broadest sense at all levels and in all sectors of Society. Municipal service delivery which is at the centre of Local Government is a complex science, art and business requiring tailor – designed institutions and suitably qualified and experienced personnel at both political and officer levels to run and manage them properly. There are no alternatives or short cuts to these basic operational requirements. Capacity building does not develop by accident. It is a product of well-planned and implemented process with adequate and appropriate investment. Paradoxically, many central governments, especially in developing countries, give lack of adequate capacity at lower levels of the governance structure as the reason for not decentralizing without making any effort to build such capacity. Yes, given the usually limited resources at the disposal of central governments against many competing demands, investing in governance capacity building may not seem to rank high on their priority list. But it is a question of what comes first between the chicken and the egg. 15 References Allen, J.B. Hubert, Cultivating the Grass roots: Why Local Government Matters, IULA Publication 1990 Balihuta, Arsene Poverty and Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2000 Cleaver, Frances, Paradoxes of Participation: Questioning Participatory Approaches to Development, in Journal of International Development 1999. Cloete, J.J.N., Accountable Government and Administration for the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Cooksey Brian, Langseth Petter and Simpkins Fiona, The National Integrity System in Tanzania; Parliametarians Workshop, Dodoma, Tanzania 10 August 1996 Economic Development Institute and the Africa Technical Department of the World Bank, Strengthening Local Governments in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1998 Langseth, Peter, Nogxina Sandile, Prinsloo, Sullivan Rogers, Civil Service Reform in Anglophone Africa, 1995. Mobogunje, Akin, Local Government Issues in Africa, 1991 UNDP, Public Sector Management, Governance, and Sustainable Human Development, UNDP Publication 1995. Olowu, Dele, Motivations and Dilemmas of Local Self-Governance in Africa, 1999. Onyach-Olaa, Martin and Porter, Doug, The Changing Responsibilities of Central Government. UNCDF – Uganda Working Brief Series, November 2000. Pope, Jeremy, Ethics, Transparency and Accountability: Putting Theory into Practice in Civil Service Reform in Anglophone Africa 1995, edited by: Langseth, Peter, Nogxina Sandile, Prinsloo, Sullivan Rogers. Ribot, Jesse C., Local Actors, Powers and Accountability in African Decentralisation: A Review of Issues, World Resource Institute, 2001 Richard, Stren and Kjellberg Bell, Urban Research in the Developing World: Perspectives on the City, 1995 Schwella, Erwin Training as a Vehicle for Change, Executive Seminars, Repositioning and Energising the Public Sector, 1990. Sudra, Thomasz, The UNCHS (HABITAT) Experience of Responding to the Global Challenge of Local Government Capacity Building, 1995 16 The Municipal Development Program, Program Document for the Eastern and Southern Africa Module 1991 The World Bank, Better Urban Services: Finding the Right Incentives, 1997 The World Bank, India: The Challenges of Development, A Country Assistance Evaluation, 2001 World Bank Institute, City Strategy and Governance, 2001 17