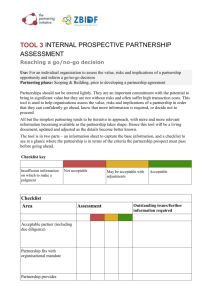

The Developing Of Capacity - Are you looking for one of those

advertisement