File

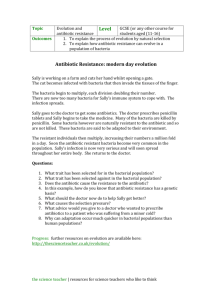

Development of Antibiotic Resistance

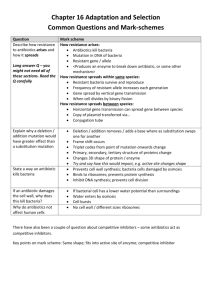

How do bacteria become resistant to antibiotics?

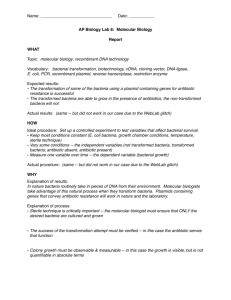

Some species may be resistant because they don't posses the antibiotic target. E.g. penicillin targets the cell wall and weakens it by inhibiting the enzymes which make peptidoglycan for the cell wall.

The bacteria which causes Chlamydia has a cell wall that does not contain with no peptidoglycan and hence penicillin will not act on it.

In general, resistance first develops due to a mutation . Bacteria reproduce asexually, so all the offspring should be the same, but sometimes, at random, mutations occur when DNA is replicated. These mutations may have any effect (and most will be fatal), but just occasionally a mutation occurs that makes that bacterium resistant to an antibiotic.

For example a mutation could slightly alter a protein so that an antibiotic can no longer bind, or a mutation could slightly alter an enzyme, changing its substrate specificity so that its active site will now bind penicillin. Such mutations are very rare, but bacteria reproduce so rapidly, and there are so many bacterial cells, that new resistance mutations do crop up at a significant rate (a few times per year somewhere on the planet). Remember that development of antibiotic resistance is a random event, and is not caused by the presence of the antibiotic. It is certainly not an adaptation that bacteria acquire.

As an example, imagine a community of different bacterial species living in your gut, and one particular cell has just mutated to become resistant to penicillin.

What happens next?

It will reproduce by binary fission and pass on its resistance gene to all its offspring, forming a new strain of bacteria in your gut. If there is no antibiotic present in your gut (most likely) this mutated strain may well die out due to competition with all the other bacteria, and the mutation will be lost again. However, if you are taking penicillin, then penicillin will be present in the bacteria's environment, and these mutated cells are now at a selective advantage: the antibiotic kills all the normal bacterial cells, leaving only the mutant cells alive. These cells can then reproduce rapidly without competition and will colonise

the whole environment. This a good example of natural selection at work.

Spread of Antibiotic Resistance

How do these resistant bacteria spread to other people?

In the example above the bacteria will contaminate faeces and may then infect other individuals through poor hygiene. In fact the resistant bacteria can spread by any of the normal methods of spreading an infection: through water, food, sneezing, infected instruments, etc. Some bacteria can form spores to aid their dispersal, and so a mutated strain can survive long journeys and long periods of time. In most new environments the mutated strain will die out through competition, but whenever it encounters penicillin it will thrive, out-competing all other bacteria.

This is how resistance of one bacterial strain to one antibiotic can spread, but unfortunately resistance can also spread between species.

Bacteria have a trick that no other organisms can do: they can transfer genes between each other; even between different species. In this way a resistance gene can spread from the bacterium in which it arose to other, perhaps more dangerous, species.