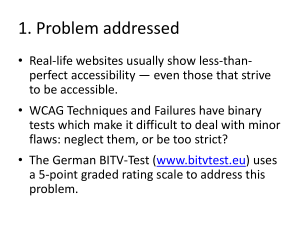

B.1 Relevance of Credit Rating Agencies

advertisement