OUTLINE – Revised 10/4/06 - Teaching American History

advertisement

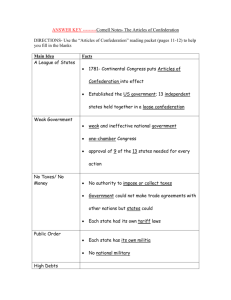

THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1787 LESSON #1: THE ROAD TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION Authors: Christopher Burkett and Patricia Dillon Introduction In February of 1787, Congress authorized a convention, to be held in Philadelphia in May of that year, for the purpose of recommending changes to the Articles of Confederation. In what has come to be known as the Constitutional Convention of 1787, all of the states – with the exception of Rhode Island – sent delegates to debate how to amend the Articles of Confederation in order to alleviate several problems experienced by the United States after the War for Independence. Although the Convention eventually decided to scrap the Articles altogether, and recommend instead the adoption of an entirely new plan of government, all of the delegates were initially united by one belief – that something must be done in order to correct the “errors” of the American political system in the 1780s. This lesson will focus on the various problems under the Articles of Confederation between 1783 and 1786 that led to the call for the 1787 Convention. By examining documents of Congress, of the state governments, and of prominent American founders – in both private and public writings – students will better understand why many Americans agreed that the Articles should be revised and amended. Students will also see why some prominent American founders, more than others, believed that the United States faced a serious crisis, and that drastic changes, rather than minor amendments, to the Articles were necessary. Guiding Question Was the Philadelphia Convention of 1787, called for by Congress to recommend amendments to the Articles of Confederation, necessary to fulfill the political principles of the American Revolution and preserve the Union? Learning Objectives After completing this lesson, students should be able to: Identify the steps taken by Americans to bring about the 1787 Convention by placing key events in historical order in a timeline. Discuss actions by several state governments that violated the Articles of Confederation, acts of Congress, their own state constitutions, and the political principles of the American Founding. Identify the powers of Congress under the Articles of Confederation, and explain why those powers were insufficient to ensure the prosperity and security of the United States. Articulate the views of several American founders about the problems of the American political system in the 1780s, and what each believed ought to be done to correct those problems. Background Information for the Teacher The 1780s promised to be a time of peace and prosperity for the United States. Having declared and won their independence from Great Britain, Americans enjoyed the freedom to establish for themselves state governments based on the principles of liberty, consent of the governed, and protection of natural rights. Most of the state constitutions included declarations of these principles, including the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776 and the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. The thirteen states had also entered “into a firm league of friendship with each other” under the Articles of Confederation, adopted in 1781, in order to promote “their common defense, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare.” The Articles of Confederation established a Congress charged with the “management of the general interests of the United States.” Americans, therefore, had established for themselves state governments to provide for the safety and happiness of their own citizens, and a national government to take care of the general interests of all the states. Such were the promising circumstances American citizens found themselves in during the early 1780s. By 1786 it had become apparent to many Americans that all was not well. There were generally three kinds of problems that contributed to the “melancholy situation” (as Alexander Hamilton called it in The Federalist No. 15) of the 1780s: first, problems within the states themselves; second, violations of the Articles of Confederation and of national treaties by the states; and third, the lack of powers on the part of Congress to get states to comply with the Articles and acts of national legislation. Within the states, the governments often acted in ways contrary to the ideal of good government as held forth in the state declarations of rights. The state governments also seemed incapable of dealing with the problem of majority factions. State governments flagrantly violated national treaties, ignored requisitions for funds passed by Congress, and continued to exercise powers prohibited by the Articles of Confederation. But arguably the most pressing problem was that the states frequently disregarded Congressional requisitions for funds to pay for national defense. Many Americans came to believe that the problems of the 1780s arose largely from defects with the Articles of Confederation, which had given Congress too little power and therefore made it incapable of dealing effectively with national problems, and of keeping the state governments in compliance. In August of 1786, some members of Congress made an attempt to remedy these problems by proposing amendments to the Articles of Confederation, but the attempt failed because of division among Congressional delegates. A discussion of these defects of the Articles took place among delegates from five states – Virginia, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York – at Annapolis, Maryland in September of 1786. The delegates to the Annapolis Convention issued a report to Congress, noting that “there are important defects in the system of the Federal Government,” and recommending that Congress authorize a convention in the following May for the purpose of addressing these defects. On February 21, 1787, Congress passed a resolution authorizing “a Convention of delegates who shall have been appointed by the several states be held at Philadelphia for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation and reporting to Congress and the several legislatures such alterations and provisions therein as shall…render the federal constitution adequate to the exigencies of Government & the preservation of the Union.” Even as the states began to commission delegates to the Philadelphia Convention, different opinions formed about what the delegates should try to accomplish there. All of the delegates agreed that the Articles of Confederation should be amended, but many disagreed over how drastic the changes should be. The differences between the two groups over the purpose of the Convention would eventually lead to deadlock during the first two months of the Convention. For more background information on the road to the 1787 Convention, see “Introduction to the Constitutional Convention” at the EDSITEment-reviewed site Teaching American History. This website also provides a very good overview of how the states selected their delegates, and detailed accounts of the views and personal background of each of the delegates. The National Archives’ “Charters of Freedom” website also offers an account of the events leading to the 1787 Convention, and includes a page of questions and answers pertaining to the Constitutional Convention. Digital History also provides a series of background pages on what is known as “The Critical Period” from 1783-1787, including Shay’s Rebellion, the Newburgh Conspiracy, and the difficulties with getting the states to comply with Congressional requisitions for funds. Preparing to Teach this Lesson Review the lesson plan. Locate and bookmark suggested materials and links from EDSITEment reviewed websites used in this lesson. Download and print out selected documents and duplicate copies as necessary for student viewing. Alternatively, excerpted versions of these documents are available as part of the Text Document. Download the Text Document for this lesson, available here as a PDF file. This file contains excerpted versions of the documents used in the first and second activities, as well as questions for students to answer. Print out and make an appropriate number of copies of the handouts you plan to use in class. Analyzing primary sources: If your students lack experience in dealing with primary sources, you might use one or more preliminary exercises to help them develop these skills. The Learning Page at the American Memory Project of the Library of Congress includes a set of such activities. Another useful resource is the Digital Classroom of the National Archives, which features a set of Document Analysis Worksheets. Finally, History Matters offers pages on "Making Sense of Maps" and "Making Sense of Oral History" which give helpful advice to teachers in getting their students to use such sources effectively. Suggested Activities 1. Problems within the states, 1783-1787 2. Problems with the Articles of Confederation 3. The Road to the 1787 Convention 1. Problems within the states, 1783-1787 Time required for activity: Homework reading assignment with questions and one 50 minute class period. Preparing for the activity: Print copies (or provide links) for students of the documents assigned as homework (listed below, included in the Text Document). Print the interest/role cards on pages 2-9 of the Text Document. Make sure that you have one card for every student in your class. Print and read the list of possible bills, available on page 1 of the Text Document. The purpose of the activity is to show how many state legislatures, after 1776, began to violate their own constitutions, which declared the rights of their citizens and established governments meant to secure those rights. As James Madison documented in his Vices of the Political System of the United States, written in April of 1787, several state legislatures passed unjust laws, and were often incapable of protecting their citizens against internal violence or rebellions. The unforeseen problem within the states was that in societies based on consent and majority rule, it is possible for the majority to pass laws that are harmful to the natural rights of the minority. In this activity, students should recognize how easy it is for dangerous factions to form in a state legislature and for laws to be passed that violate the rights of the minority. This activity will illustrate one major problem that led Americans in the 1780s to call for revisions to the Articles of Confederation by increasing the authority of Congress and limiting the powers of the individual states. On the day before the activity: For homework on the night before the activity, assign the following to your students, excerpts of which are available on pages 10-12 of the Text Document: 1. Read the following documents, available at the EDSITEment reviewed Avalon Project at Yale University [http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon] and Teaching American History [http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com]. A. Declaration of Independence, 1776 (first two paragraphs only) http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=1 B. Virginia Declaration of Rights, 1776 http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/virginia.htm C. Massachusetts Constitution, Preamble, 1780 http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=266 2. Write a one-paragraph answer to each of the following questions (these are also listed on the Analysis Sheet found on pages 13-14 of the Text Document) A. What is the purpose of each document? B. What are the main principles put forth in each document? C. What are the rights listed in each of the documents? D. Why is electing representatives necessary? E. What are some of the responsibilities of government? F. Why do people create governments? G. What are some things governments should not do? H. What might happen if government fails to keep rights secure? I. How do these documents promote the idea of self-government? On the day of the activity: The activity involves role playing, in which students will be delegates to a state legislature (either Virginia or Massachusetts, at the teacher’s discretion) representing different interests within their state. The immediate purpose of the activity is to have students try to pass a bill that agrees with their group’s interests; but the larger purpose is to show them how easy it is for factions to form in legislatures, and also how easy it is to pass a law that violates the rights of the minority. Randomly distribute one interest/role card to each student (the cards can be printed from pages 2-9 of the Text Document). These cards provide the student with background information on the interests he or she represents. As presiding officer in the state legislature, the teacher introduces one of the bills from the list on page 1 of the Text Document. The teacher should then open the floor for discussion of the proposed bill for a total of 10 minutes. Students should have no more than 30 seconds at a time to make comments on the proposed bill. When recognized to speak, each student should state his or her interest as it is listed on the role card. The goal is to get students to think about whether the bill seems to coincide with the interest they have been given on their role playing card. After 10 minutes of open discussion, the legislature should adjourn for 10 minutes. During this period, students should form into groups to discuss the pros and cons of the proposed bill. Based on comments during the open floor discussion, students will form into groups with like-minded representatives (that is, those in favor of the bill will form into a group, those against in another group – or perhaps several smaller groups will form). Each group should work together to compile a list of arguments as to why they are for or against the bill. They will select one of their members to present their arguments to the class. Upon resuming the legislative session, the presiding officer (teacher) should call for the representative of each group to make a short presentation (2 minute maximum each) of their arguments for or against the bill. The presiding officer (teacher) should call for a preliminary vote. Upon tallying the totals, the teacher should remind students of the principles included in their state’s constitution or declaration of rights (either Virginia or Massachusetts, as selected by the teacher) and raise the possibility that the bill might violate one of those principles. Afterwards, the teacher should reopen the floor for general discussion for 5-10 minutes. After 5-10 minutes of open discussion, a final vote should be taken. Students should then be separated into groups representing each interest, at which time they should declare whether they will abide by the law or not, and what course of action they will take (perhaps some will comply, others will protest, and others might take more drastic measures). The teacher should then explain how either a majority or minority (or both) faction has formed. Teachers have the option of extending the activity by assigning the following for homework: Write a one to two page essay on how factions develop and the dangers of majority factions in a representative democracy (Teachers: if you are going to move on to Activity #2 on the following day, be aware that you will need to assign the readings for the next exercise as well). 2. Problems with the Articles of Confederation Time required for the activity: Homework reading and writing assignments and two 50 minute class periods for presentations and role play. Preparing for the activity: Print copies (or provide links) for students of the documents assigned as homework (listed below, included on pages 27-31 of the Text Document). Print a copy of the List of Possible Resolutions for debate, located on pages 15-17 of the Text Document. Print the “State Delegate” cards provided on pages 23-26 of the Text Document (be sure to print enough to each student in your class). Print the State ID name placards from pages 18-23 of the Text Document. Optional: Print the Graphic Organizer (included on page 33 of the Text Document) and give a copy to each student (only if you will not complete part 2 of this activity). The purpose of this activity is to get students to understand the problems that resulted from the defects of the Articles of Confederation, and to show how incapable Congress was of fulfilling its responsibilities. Those responsibilities included: Raising funds from the states to defray the costs of defense and the war against Great Britain Managing foreign relations for all of the states, including making treaties and alliances with foreign nations Paying both domestic and foreign debts incurred by the United States Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress lacked sufficient authority to get states to comply with acts of Congress. Students should see that these problems resulted from two causes. First, the states had jealously surrendered very limited powers to the national government under the Articles, and as a result, Congress had no means of compelling states to comply with requests for funds or to refrain from violating the Articles of Confederation. Second, students should recognize the difficulties inherent in the structure of Congress under the Articles. Congress was comprised of one house, and each state had one vote on all matters. The legislatures of each state selected their delegates to Congress, and had the power to recall them at any time. Furthermore, nine of thirteen states had to agree to any Congressional request for funds from the states. In this activity students will see that because the state delegations were inclined to represent the interests of their own state, rather than what was necessary for the good of the whole Union, congressional debates frequently became deadlocked. If Congress was actually able to muster nine votes in favor of a requisition, they still had to rely on the good will of the states for compliance. This system of government, Madison lamented in his Vices of the Political System of the United States, was wholly unworkable, and must be revised for the future safety and happiness of American citizens. On the day before the first part of the activity: Divide the class into 7 groups, and assign each group one of the following documents for homework, available at the EDSITEment reviewed Teaching American History website [http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com]. The relevant excerpts are available on pages 27-33 of the Text Document. Group 1: Excerpt from James Madison, The Federalist No. 15 http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=759 Group 2: Robert Morris to the President of Congress, 17 Mar. 1783 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1588 Group 3: Gouverneur Morris to John Jay, 1 Jan. 1783 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1583 Group 4: George Washington to James Warren, 7 Oct. 1785 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=312 Group 5: Rufus King to Elbridge Gerry, 30 April 1786 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1589 Group 6: George Washington to John Jay, 15 August 1786 http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=370 Group 7: John Jay to Thomas Jefferson, 27 October 1786 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1586 Students should answer the assigned discussion questions for their reading (Discussion Questions can be found on page 34 of the Text Document). They should especially be able to identify the specific problem(s) under the Articles of Confederation discussed by the author. On the first day of the activity (Part 1 of Activity 2): Split students into their groups to compare and discuss their answers to the Document Analysis/Discussion Questions assignment. Using the answers on the Discussion Questions, each group will prepare a short class presentation on their assigned document. Group discussion should take no more than 15 minutes. Then each group should make their presentation (about 23 minutes each). Teachers: If you do not intend to use the second part of the activity, you can extend this activity by having students record information from the in-class presentations by filling out the Graphic Organizer (included on page 35 of the Text Document). Have them write an essay on “Problems with the Articles of Confederation,” using their notes from their Graphic Organizer and the inclass presentations. If you intend to continue with the second part of the activity, for homework that evening students should read the Articles of Confederation [http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/artconf.htm], available at the EDSITEment reviewed Avalon Project at Yale University [http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon]. Excerpts are available on pages 36-37 of the Text Document. Discussion questions may be found on pages 38-39 of the Text Document, and these should also be assigned for homework questions. On the second day of the activity (Part 2 of Activity 2): In this role playing activity, students will be delegates from the states to Congress. Divide students into at least 7 groups. It is not necessary to have the same number of students in each group – there should be at least 2 and no more than 7 in each group, however. Each group will represent a delegation from a particular state. Each student should be given a “State Delegate” card, which tells which state he or she represents, something about the state, and the particular interests the delegate represents. Also, give each state delegation their state ID name placard so that the other students know who they are representing. All of these are available on pages 18-26 of the Text Document. A presiding officer for the Congress should be selected through nomination and vote—each state group having only one vote. Then the presiding officer should announce the first resolution for debate (as selected by the teacher from the list found on pages 15-17 of the Text Document). Each state should meet for 5 minutes to discuss and prepare a short speech (1 minute) in support of or against the resolution. This speech should include reasons why other states ought to support or oppose the resolution. The presiding officer should oversee these deliberations. After this debate has concluded, the presiding officer will call for a vote. These basic concepts should be kept in mind: Each state delegation casts one vote, determined by the majority within each group. If delegates do not like a resolution, they can receive a letter from their state legislature recalling them back to their state. In this case they do not get to vote on the resolution. 5 of 7 states (or two-thirds, if more than 7 states are in play) must agree in order to pass a resolution to make a treaty, raise money, or borrow money. 4 of 7 states (or a simple majority, if more than 7 states are in play) must agree for all other resolutions. All requisitions for funds will be paid by the states in proportion to one of the following (depending on which resolution is introduced): o Land Value (as indicated on State Delegate Cards). o Population (as indicated on State Delegate Cards) o Annual State Wealth (as indicated on State Delegate Cards) For resolutions that tax or otherwise affect imported or exported goods, students should be aware of the Import/Export ratio listed on their state delegate card. The first number represents imports, the second number represents exports. Those states with a lower first number export many more goods than they import. For example, a state with an Import/Export ratio of 1:10 exports ten times as many goods than it imports. Those states with a higher first number rely more on imported goods than those with a lower first number. For example, a state with an Import/Export ratio of 10:10 imports the same amount of goods as it exports. Further resolutions can be introduced and debated at the teacher’s discretion, depending on time. After the final vote on each resolution, the teacher should read the consequences of the vote (included in the List of Possible Resolutions for Debate on pages 15-17 of the Text Document). For example, if the resolution was to raise money to pay the army, and the resolution passed, Rhode Island might refuse to pay; if it doesn’t pass, there might be a mutiny among the army. This activity could be extended with a written assignment in which students should analyze why the voting outcomes occurred as they did. What arguments were effective? Which states joined to support or to oppose? What could have been done or said to alter the outcome? Students might also write about how difficult it was to get a resolution passed by Congress under the Articles of Confederation. 3. The Road to the 1787 Convention Time required for the activity: If research is done for homework, one 50 minute class period for presentations. Preparing for the activity: Print copies (or provide links) for students of the documents assigned as homework (listed below, included on pages 40-52 of the Text Document). The teacher should create a basic timeline on a classroom wall spanning 1780 to 1787 (approximately 90” x 16”). Distribute one 5” x 7” piece of cardstock to each group of students (9 groups total). The purpose of this activity is to allow students to develop an understanding of the events that led to the 1787 Convention in Philadelphia. Students should gain an appreciation for the “melancholy situation,” as Alexander Hamilton would later call it in The Federalist No. 15, in which Americans found themselves under the Articles of Confederation. Students should also see how long it took – and why it took several years – to actually organize a convention to remedy the defects of the Articles of Confederation. On the day before the activity: Assign one of the following topics/documents to groups of 2-3 students (Teachers: these documents can be used to supplement information found in the textbook you are using for class). Each document represents a significant step leading up to the 1787 Convention. All of these documents are available at the EDSITEment reviewed resources Avalon Project at Yale University [http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon], Teaching American History [http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com], and American Memory [http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html], but relevant excerpts are included on pages 40-52 of the Text Document. Group 1: Spain closes navigation of the Mississippi River to American ships http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(dc004516)) Group 2: Unpaid Soldiers and the Newburgh Conspiracy http://memory.loc.gov/learn/features/timeline/amrev/peace/newburgh.html Group 3: Lack of U.S. Naval Strength to promote and protect commerce http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(dg022464)) Group 4: Congress is unable to raise revenue and repay Revolutionary War debts http://rs6.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc030149)) Group 5: Massachusetts farmers take up arms in Shays’ Rebellion http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1092 Group 6: Continental Congress proposes amendments to the Articles of Confederation, but cannot muster enough votes among the states to pass them http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1587 Group 7: Annapolis Convention in 1786 recommends revising the Articles of Confederation http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/amerdoc/annapoli.htm Group 8: Congress calls for a Convention in Philadelphia in May of 1787 to amend the Articles of Confederation http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/const/const04.htm Group 9: Philadelphia Convention begins in 1787 http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/convention/debates/0514.html On the day of the activity: Students should meet in groups (10-15 minutes) to discuss their assigned document, and prepare their timeline card. Then each group should make a short presentation (2-4 minutes each) on the main points of their research and assigned document. Prior to the presentations, the teacher will create a basic timeline on a classroom wall spanning 1780 to 1787. Each student group should list the important points of their presentation on a 5” x 7” piece of cardstock. These cards should also contain the topics and dates. As students complete the classroom presentation, one member places his or her group’s card on the timeline at the appropriate place. Alternate Activity: Teachers may give each student an individual timeline which spans 1780 to 1787. There should be enough space between the years for students to add topics and short descriptions as groups give the presentations. Assessment After completing this lesson, students should be able to write brief (1-2 paragraph) essays answering the following questions: What were the major problems or events that eventually led to the call for a 1787 Convention in Philadelphia to amend the Articles of Confederation? What were the views of some prominent American founders about the problems of the Union under the Articles of Confederation? What were the fundamental principles of American government contained in the Declaration of Independence and state constitutions between 1776 and 1780? What were the main problems within the states between 1776 and 1787 that caused them to act contrary to the principles of the American Revolution? What were the powers and responsibilities of Congress under the Articles of Confederation? How were delegates selected for Congress under the Articles of Confederation, and how were resolutions voted on and passed? Why was it so difficult to pass resolutions in Congress under the Articles of Confederation? What were the defects of the Articles of Confederation that prevented Congress from fulfilling its responsibilities? Why, for example, was it so difficult for Congress to raise funds? Students should also be able to debate the need for a new form of government to replace the Articles of Confederation, and write a longer (1-2 pages) essay answering the following question: Do you think there was any point between 1780 and 1789 that the outcome (that is, doing away with the Articles) could have been avoided? At what point might this have occurred, and what changes would have been needed to alter the outcome? An alternative method of assessment might be to divide the class into small groups, and have each one develop a thesis statement that encompasses all the various elements of this lesson. They should be given roughly 15 minutes to do this. Once they have done so, each group should write its thesis statement on the board, and as a class discuss which is the best, and why. The entire class could then be given a homework assignment to write an essay that defends the statement. Students should be able to identify and explain the significance of the following: The Virginia Declaration of Rights, 1776 Massachusetts Constitution, 1780 The Newburgh Conspiracy Spain and navigation on the Mississippi River Articles of Confederation Shays’ Rebellion Annapolis Convention, 1786 Philadelphia Convention, 1787 Congress’ inability to pay Revolutionary War debts Extending the Lesson PBS’ “Liberty!” website has suggested activities on “Creating a New Nation,” including the problems under the Articles of Confederation after the War for Independence. Teachers can also extend this lesson by engaging in the following supplemental activities: 1. Create a PowerPoint documenting the Road to the Constitutional Convention 2. Write a Persuasive Essay or Letter to the editor of a newspaper. Convince your reader that the Articles must be changed. Letter could be to a Rhode Island newspaper, for example. 3. Create and perform a one-act skit that highlights a discussion on a problem with a state legislature or the Articles of Confederation. Next Lesson Plan Return to the Curriculum Unit Overview — Related EDSITEment Lesson Plans Selected EDSITEment Websites The following links are only those that are directly referred to in this lesson plan. American Memory o The Newburgh Conspiracy http://memory.loc.gov/learn/features/timeline/amrev/peace/newburgh.html o John Jay to President of Congress on Spain closing navigation of the Mississippi http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(dc004516)) o Continental Congress on the Payment of Revolutionary War Debts http://rs6.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc030149)) o James McHenry to George Washington on the Payment of Revolutionary War Debts http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(dg022464)) The Avalon Project at Yale Law School o Articles of Confederation http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/artconf.htm o Virginia Declaration of Rights, 1776 http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/virginia.htm o Proceedings of Commissioners to Remedy Defects of the Federal Government, Annapolis Convention, 1786 http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/amerdoc/annapoli.htm o Report of Proceedings in Congress (calling for 1787 Convention) http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/const/const04.htm PBS’ Rediscovering George Washington o George Washington, Address to Officers at Newburgh, NY, 1783 http://www.pbs.org/georgewashington/multimedia/arnn/newburgh.html TeachingAmericanHistory.com o Declaration of Independence, 1776 http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=1 o Massachusetts Constitution, 1780 http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=266 o U.S. Constitution http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=2 o Bill of Rights (Amendments I – X of U.S. Constitution) http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=272 o The Federalist No. 15 http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=759 o James Madison, Vices of the Political System of the United States, 1787 http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=802 o Continental Congress, Report on Proposed Amendments, 1786 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1587 o Edmund Randolph to James Madison, 27 March 1787 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1581 o James Madison to Edmund Randolph, 8 April 1787 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1584 o Robert Morris to the President of Congress, 17 Mar. 1783 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1588 o Gouverneur Morris to John Jay, 1 Jan. 1783 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1583 o George Washington to James Warren, 7 Oct. 1785 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=312 o Rufus King to Elbridge Gerry, 30 April 1786 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1589 o George Washington to John Jay, 15 August 1786 http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=370 o John Jay to Thomas Jefferson, 27 October 1786 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1586 o John Jay to George Washington, 7 January 1787 http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1585 Additional Information: Grade Levels: 9-12 Subject Areas U.S History – Civics and U.S. Government Time required Four class periods Skills: Analyzing primary source documents Interpreting written information Making inferences and drawing conclusions Observing and describing Representing ideas and information orally, graphically and in writing. Utilizing the writing process Utilizing technology for research and study of primary source documents Vocabulary development Working Collaboratively Curriculum Unit: The Constitutional Convention of 1787 o The Road to the Constitutional Convention o The Question of Representation at the 1787 Convention o Debating the Powers of the Presidency at the 1787 Convention Additional Student/Teacher Resources “The Road to the Constitutional Convention” downloadable PDF file Author(s) Christopher Burkett Ashland University Ashland, Ohio Patricia Dillon Feedback Send us your thoughts about this lesson! Email this Lesson Send this lesson to friends or colleagues