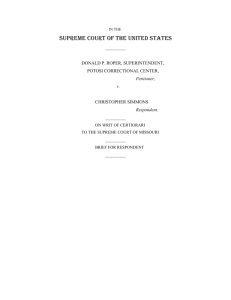

Roper, Donald, Supt

advertisement

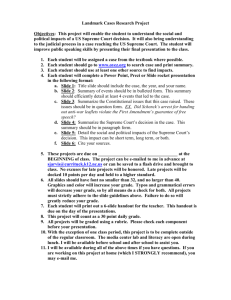

Roper, Donald, Supt., Potosi Correctional Center v. Simmons, Christopher Docket: 03-0633 Term: 04-05 Appealed From: Missouri Supreme Court (Aug. 26, 2003) Oral Argument: Oct. 13, 2004 Opinion Issued: Subject: Capital case, juvenile offenders, 8th Amendment , "evolving standards of decency" Questions presented: (1) Once the Supreme Court held in Stanford v. Kentucky, 492 U.S. 361 (1989) that capital punishment for those under 16 is not "cruel and unusual" and thus barred by the 8th and 14th Amendments, can a lower court reach a contrary decision based on its own analysis of evolving standards? (2) Is the imposition of the death penalty on a person who commits a murder at age 17 "cruel and unusual" and thus barred by the 8th and 14th Amendments? BY BETH SHAYNE, MEDILL NEWS SERVICE In Mineral Point, Missouri, at the Potosi Correctional Center, a young man named Christopher Simmons awaits a death sentence that was ordered for him in 1993, a year in which he was only 17 and a juvenile in the eyes of the law. In pleading for his pardon over the years, his attorneys have drawn a picture of Simmons as a model prisoner committed to God and his own recovery. It's a far cry from the person they say he was a decade ago, a confused child marred by a history of physical abuse, drug use, rejection and mental illness. On Sept. 9, 1993, Simmons broke into the suburban St. Louis home of Shirley Crook with the intention to rob and then kill her, presumably for the thrill of the crime. As soon as his unfortunate victim identified him in the midst of the break-in, Simmons and a friend tied her up with duct tape and drove her to a nearby state park. There, he wrapped her in electrical cable, leather straps and a towel before pushing her off a bridge into the Meramac River where she drowned. According to prosecutors at his trial months later, Simmons had talked about this plan with his friends on several occasions, assuring them they wouldnt be punished because they were juveniles in the eyes of the law. A doctor who evaluated him years after the incident added that Simmons had downed 12 beers and smoked marijuana on the evening of the murder. The boys were arrested the following day and Simmons confessed on videotape at the police station. At trial, a jury easily found him guilty. At his sentencing hearing, his defense attorneys asked for leniency based on his age, but the jury focused on the brutal and aggravated nature of the crime and sentenced Simmons to death by lethal injection. The sentence would make Simmons the second juvenile ever executed in Missouri, and the seventh youth in the nation to be put to death since the U.S. Supreme Courts last review of the issue in 1989. As Simmons waited on death row, federal and state courts rejected a number of pleas for postconviction relief, habeas corpus and appeal on his behalf. Just before he was scheduled to die in May of 2002, the Missouri Supreme Court stayed his execution while the U.S. Supreme Court heard another case on the death penalty with regards to mentally retarded offenders. In Atkins v. Virginia, the Supreme Court determined that executing the mentally ill was a "cruel and unusual punishment" in the eyes of a majority of Americans. The standards of review the majority used, in an opinion written by Justice John Paul Stevens, compelled the Missouri court to reconsider a review in Simmons case. The courts issue was never with the boys guilt, but with the general constitutionality and morality of the juvenile execution with respect to the ""cruel and unusual punishment"" clause of the 8th Amendment. The constitutional practice with the cruelty standard is to consider it against "evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society," as Chief Justice Earl Warren first put it in 1958 in Trop v. Dulles. In 1989, in Stanford v. Kentucky, the Supreme Court last examined those standards of decency regarding juvenile execution. Then, the Court, by a 5-4 vote, affirmed execution in the case of a 16-year-old Kentucky youth convicted of murder. The majority acknowledged age as a mitigating factor in death sentencing, but, in an opinion written by Justice Antonin Scalia, said the national climate didnt rule out the death penalty simply because of the age of the offender. On Aug. 23, 2003, the Missouri Supreme Court took it upon itself to reopen the debate. Using Simmons case, the states highest court found "a national consensus has developed against the execution of juvenile offenders." The 6-3 majority opinion, written by Judge Laura Denvir Stith, cited 12 state laws banning all executions, five laws creating a minimum age of 18 for the death penalty, and a number of statistics that speak to the rarity of such a sentence in this day and age. The opinion stressed the 4-prong standard of review used in Atkins v. Virginia, decided the year before regarding the mentally ill, as opposed to a more limited list the court applied in 1989 when it last considered juvenile execution. Stith wrote that the Supreme Court was remiss in discounting what it recognized as "the lesser culpability and developing nature of the adolescent mind" in 1989. In 2003, the Missouri court "stressed this difference." The 4-part standard the majority applied also added the weight of statements from national and international organizations against juvenile execution as part of evaluating "evolving standards of decency." It specifically cited the disapproval of scores of legal, medical, and faith-based organizations, among them the American Psychiatric Association, The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and The Coalition for Juvenile Justice. A concurring opinion from Judge Michael Wolff recommended to the U.S. Supreme Court that it review the case. He openly expressed a fear that the bench would refuse to use age as "a bright line in juvenile death penalty cases" as it did in 1989, and so encouraged that it should, at minimum, adopt a presumption "that persons below the age of 18 are presumed to lack sufficient maturity to be eligible for the death penalty." This presumption, he said, leaves the door open for exceptionally mature offenders to be sentenced in kind. With regard to the case before them, the Missouri Supreme Court re-sentenced Simmons to life in prison. The dissenters, in an opinion written by Judge William Ray Price, Jr., deferred to the higher courts 1989 ruling, saying, "The United States Supreme Court has not overruled Stanford, even in light of its decision in Atkins v. Virginia. This court is bound by the United States Supreme Courts decision in Stanford v. Kentucky and simply has no authority to overrule that decision." This was also the crux of the Missouri attorney generals argument when he sought review from the U.S. Supreme Court. "[I]f the Missouri path remains unblocked, there will be no logical barrier to courts holding that acts this court once held to be Ôcruel and unusual no longer fit that description," the petition for certiorari argues. "Again, that would sow inequity and wreak havoc throughout the justice system." Further, the petition for certiorari accuses the Missouri Supreme Court of deriving a "rationale" from Atkins and unfairly applying it as a "holding" to Simmons case. The petition calls on the Supreme Court to clean up the "analytical debris" left by the state court. On Jan. 26, 2003, the Court accepted Simmons case for review without costs in keeping with an urgency expressed by all parties to set a clear, new standard for "cruel and unusual punishment."