Infusing technology in Australian teaching and learning

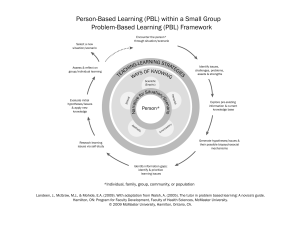

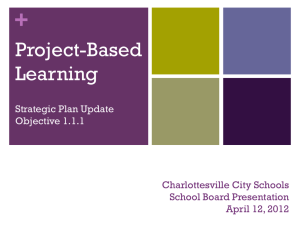

advertisement

Premier’s Harvey Norman Information and Communication Technologies Scholarship Infusing technology in Australian teaching and learning through the use of project-based learning Kathryn Burke Our Lady of the Rosary Catholic Primary School, Waitara Sponsored by Schooling is an 18th Century institution using 19th Century structures teaching 20th Century curriculum to 21st Century students. —Mark McCrindle, social trend researcher, 2005 A current challenge for many educators in Australia is to find ways to engage and educate our 21st century students and prepare them for the 21st century world. A key part of this involves finding ways to use technology appropriately, in meaningful situations and in ways that infuse technology into an already crowded curriculum. Australian educators have seen the rise of webquests, information or knowledge quests, online learning games and educational CD-ROMs, yet, as an educator, I found many of these resources lacked a real-world use of technology in which children were expected to apply skills and knowledge to genuine problems for genuine uses. In building upon and moving beyond these resources and strategies in my classroom, I have tried to find realistic uses of technology for students’ learning, where technology is infused into a ‘just in time’ learning environment similar to that of real life. Through postgraduate work and action research, I began to use project-based learning (PBL) as a way to meet the challenge. I have found that PBL allowed for the integrated technology outcomes of the NSW Board of Studies K–6 Syllabus to be addressed, while ensuring that the teaching and learning remained focused just as importantly on learning outcomes and 21st century skills. PBL is more than a webquest or Internet research task. When used effectively, research has shown that PBL helps teachers create a high-performing classroom in which teachers and students form a powerful learning community. The aim is for real-life context and technology to meet and achieve outcomes in the curriculum through an inquiry-based approach. A PBL approach is designed to encourage students to become independent workers, critical thinkers, and lifelong learners. Many teachers and researches involved in PBL believe it makes school more meaningful as it provides in-depth investigations of real-world topics and significant issues worthy of each individual student’s attention and investigation. Over the last few years I have seen evidence to various extents of this in my own classroom when I use project-based learning with my students. While PBL is not a new concept, I felt that awareness of the possibilities of project-based learning are only beginning to disseminate through the Australian teaching community. While a wealth of PBL resources, research and information can be found on the Internet, I have found that these are usually based in countries other than Australia (mainly the United States and the United Kingdom) and are geared towards different syllabuses. The United States has been exploring possibilities of PBL for at least the last decade and has invested in many school-based programs, as well as creating two world renowned institutes, the Buck Institute for Education and the Rutgers Center for Education. As a classroom teacher who has been implementing features of PBL in my own school setting, I have become aware of both the obvious strengths of PBL, and also areas in which I felt inadequately trained to implement it well. While digitally recording the PBL process in my classroom and communicating with lecturers from Australian Catholic University who use PBL in their online postgraduate education courses has been one way to combat this, I felt that I was still lacking in my depth of experience and knowledge of how to best implement PBL in a school setting. Without any concrete working school models in Australia to build upon, I decided to observe possibilities being trialled in the United States in order to gain the practical understandings that would then allow better implementation of PBL in my own classroom setting, as well as a more refined approach to help achieve technology syllabus outcomes, which could then be shared with the wider teaching community so more teachers could consider how best to infuse technology into Australian teaching and learning. Study focus Over the course of four weeks, I visited a variety of schools in the United States. These schools were in different geographical parts of the United States, and the students were of different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. Several of the schools included on the itinerary were in inner city environments, while some where in urban and even semirural areas. Some of the schools were newly established (within the last five years), while some have been part of their communities for decades. Schools visited included preschool, elementary, middle and high school levels of education. The thing that all of these schools had in common was that they purported themselves as schools of innovation that used PBL as a way to educate their 21st century students. I developed a set of key questions to aid in the gathering of data from each school. An aim of gathering this common information was to aid in the comparison between schools to better gain an understanding of what was working and if any commonalities were found in the successful use of PBL. These key questions were as follows: The big ideas behind the school—What philosophy has the school built its programs and innovation around? What led the school to this philosophy/program (the journey undertaken)? How long has this innovation been going on? Specific observations about teaching and learning—What specific strategies have been seen in use by teachers and students? How do the children react to this type of learning and how do they engage in their learning? Validity and assessment of results—What evidence is there that this philosophy and these strategies are adding value? What indicators of success does the school refer to? How does the school succeed with this innovation, while still meeting state requirements? Professional development of staff—How have the staff been professionally developed and supported? Community reaction and interactions—What interaction with wider community and other professionals have taken place as a part of or a result of this innovation? What are parent reactions and interactions to this innovation? By gathering data and anecdotal evidence through classroom observations and meetings that answered this set of questions, a snapshot of learning and teaching within the school was established and insights gained into how schools were trying to cater to these 21st century learners through the use of technology and PBL. The schools were very generous in the sharing of their documents and policies which further explained their work. Talking to students, teachers and administrators as well as members of the parent community formed a part of the study focus to try to evaluate how different stakeholders viewed the use of technology and PBL. A variety of different views and responses where gathered from different schools that presented some consolidating and some conflicting views. This presented an opportunity for more focused questioning about the role of technology and projects as a viable method. Significant learnings Many of the schools using PBL chose to do so because they recognised that there was a need to change the way students were taught, to heighten engagement in learning and so improve learning outcomes, as well as other outcomes such as pro-social behaviour, work ethics and responsibility PBL computer classroom at Mount Diablo High School, San Francisco, CA. Technology coordinator small group teaching at Harrison Middle School, Yarmouth, MA. for self. These schools had a philosophy that focused on infusing technology into learning, which has been a vitally important part of their success as it showed students they were recognised by their school, families and local community as 21st century learners who are part of the ‘digital age’. The most successful school innovations also tended to be placed within the broader context of their focus on the questions: ‘What is powerful learning?’, ‘What is powerful to learn in the 21st century?’ and ‘What are powerful ways to teach in the 21st century?’ As part of this, the most successful schools also made cooperative learning a part of their philosophy. Students in these effective PBL schools saw themselves as successful learners who were competent, cooperative and responsible. At Mount Diablo High School, the teachers in charge of coordinating the PBL program talked about how the rooms are opened early and stay open till late, and that students are always working on their projects in their own time, going the extra mile. They talked of students borrowing equipment so that they could do more work on weekends. Within this school the teachers themselves were great models of passionate and cooperative people for the students. The founding teacher actually returns to work in the classroom for free with the lead teacher even though he retired five years ago. Within this room students were helping each other to complete tasks by deadline, calling on students with different specialities. The use of cooperative learning and time for collaboration was an essential part of PBL as it allowed students and teachers to help disseminate knowledge and learning through the learning community. At Harrison Middle School, cooperative learning was also observed to be a powerful tool, not only between students but between teachers. The full-time technology coordinator explained how a lot of professional development work was conducted oneon-one, as well as a lot of modelling and teaching inside the classroom. Even though Yarmouth is part of the Maine 1 to 1 laptop program, students still regularly work together on different tasks and projects, sharing skills and ideas. The 1 to 1 laptop program in itself was a powerful thing to observe. Enabling students to simultaneously develop their projects with the data projector in every classroom made it very simple for the teacher to display different pieces of work for inspiration and constructive feedback by peers. In one social studies class, the laptops enabled students to have autonomy over their learning and contributions to a discussion on current events, as students accessed a multitude of news sites simultaneously, drawing on different sources and comparing them to discuss different issues. At Sir Francis Drake High School, students had a fair degree of autonomy about their learning; however, this was achieved through careful scaffolding by teachers. This autonomy begins with Collaboration rubric used by students at Sir Francis Drake High School, San Anselmo, CA. CAD-CAM design for a machinery project investigating the use of motors at Sir Francis Drake High School. the students and parents choosing what sort of schooling they would like to receive, as this school operates on a ‘schools within schools’ model, in which different academies focus on different skills and uses of technology. Of great interest was the Media Academy, where the students had to investigate, interview and create a researched and quality documentary of collaboration rubric used by students a local historical issue, which was eventually presented to the community at a film festival. It was also at this school that students discussed how grading works, with the possibility of students negotiating scores between team-mates until all members feel that individual effort has been fairly accounted for. In addition, a common philosophy across these successful schools was the belief in smaller class sizes, and the value of students feeling part of a group, not just another face in a crowd. This seemed integral to the successful running of projects where students are working as part of a team. It was at Sir Francis Drake that the importance and, in fact, the power of goal-setting, self-assessment, feedback and reflection to improve learning also made clear. Rubrics were the major strategy for making clear to teachers and students how work and learning was valued and assessed. Goal-setting important as it enabled individuals teams to keep to a time line and to achieve the completion of a quality project illustrating their learning within set time frames. It also facilitated better cooperative learning, as each team member was aware of what they were responsible for achieving. Assessment by each student and their peers was in some cases even more sought after and valuable than that given by the teacher. Reflection on how the project had gone, and what could be done differently was not only part of the learning process of the students, but that of the teachers, who then modified and improved projects for future use, or discarded them as not suitable for use again. Throughout the schools using PBL, different students were found using tools such as word processors, spreadsheets, databases and specialised software to perform tasks and create records of their learning. In many cases students were competently using industry standard software, such as Adobe Photoshop. At Sir Francis Drake High School, Year 9 students were using Computer Aided Design and Computer Assisted Manufacturing (CAD-CAM) to create and make their own motors. Special relationships with the wider business community, in this case the Autodesk Foundation, enabled the school to maintain and upgrade software as necessary, while Autodesk developed partnerships with future engineers. This is a great example of how technology and PBL is helping to bridge the gap between life learning and school learning. Students at many schools used applications to facilitate communication and collaboration with the world outside the classroom to help them gain further understanding and to elicit expert responses to their research, which are criteria for PBL. The Internet provided students with Teacher pedagogy is just as important as the presence of technology at West Bronx Academy for the Future: access to virtual simulations and excursions, libraries, and remote physical locations for research without which they would have been unable to gain a deeper understanding of their content. Technology also played a role in the assessment and evaluation of student work, as it was used to help share work with other stakeholders, and in some instances work was even published on the Internet for a real purpose and for review by real audiences. All of these skills are listed in various syllabus documents as those skills we want our students to develop to succeed in the 21st century. An invaluable focus observed in several schools was providing and maintaining varied opportunities for parents to access information, to provide feedback and to be involved in the educational experience. The power of technology in making their children’s learning visible through multimedia presentations created by the students, as well as the possibilities of connectivity enabling anytime anywhere learning has also increased communication between home and school. An example of this is at the West Bronx Academy in New York, where and parents use Moodle (an open source e-learning platform) to enable them to access grades, assignments and work from anywhere. In addition to the parent community, the best examples of PBL in action placed great importance on finding ways to involve the wider community in order to make the learning of these children as ‘real world’ as possible. Many businesses and advisors have taken part in these projects, giving advice and donating materials and to the student’s artefacts. Mount Diablo’s Annual Business Fair involved not only a judging panel of real local business people and entrepreneurs, but a night-time presentation where hundreds of local community members and businesses were welcomed to a trade fair to ‘invest’ in the different marketing companies established by the Year 11 and 12 students based upon their business plans, marketing and product quality. To give an indication of the standard of this project-based learning, several teams were advised by the judges to take out patents before presenting at the trade fair. Through the project process, students at this PBL School demonstrated team skills, and in particular better conflict resolution skills. Many students were observed by the teacher to be relying on a wider repertoire of strategies to solve problems before seeking teacher intervention. The ability to paraphrase and to ‘piggyback’ on each other’s ideas was a feature of classroom discussions. In some schools, students also independently used team strategies to structure their time and tasks. The students’ remarkable ability to articulate what they are learning and what they are thinking was a clear distinction in the schools that were effectively using PBL. The project presentations days seemed to be the perfect example of the students’ ability to articulate their thinking, learning and reflecting on the process. The presentation days appeared to be a definite highlight for the whole community, involving not only the students and teachers, but the parents and local community. Some schools who thought they were PBL schools in reality proved to be disappointing when compared to the criteria that establish authentic project-based learning. Mistaking the use of projects as a part of learning with PBL as a pedagogical approach seemed to be the major confusion these schools had. Projects versus project-based learning: ensuring rigour and relevance Projects Loose set of activities Supplements the curriculum Thematic Broad assessments No management structure Project-based learning Inquiry based, use driving question as a focus Part of the curriculum Focused Aligns specified outcomes with assessments Uses strategies and project management to structure learning Newsome Park Elementary used to be a lighthouse school for PBL. Unfortunately, the current political climate and the ‘No Child Left Behind’ policy, which introduced new assessing and reporting requirements, has resulted in the loss of authentic project-based learning at this school. With the threat of school closure if standards are not reached, teachers are too busy constantly assessing and preparing students for testing to be able to devote time needed to deeply explore concepts and to develop deep understandings. How to engage students in PBL while meeting state requirements is something this school is struggling with. The unfortunate result seems to be the slipping of powerful learning into mere projects and teacher-directed lessons. Technology as a true tool for learning is lost as there simply is no time to allow students self-directed inquiry. As explained by the principal, the state-wide and district testing does not test the skills and deeper understandings gained by students by completing project-based learning. The tests are heavily content orientated, and more concerned with breadth than depth of understanding. Teachers comment regularly on how much children learn, then forget, and how much time they spend reteaching content in this current environment, yet no solution is apparent. Luckily, in Australia, our current assessing and reporting allows for schools to use pedagogy like PBL to develop skills and deeper understandings. State-wide testing is more focused on skills like understanding, interpreting and problem-solving, which is a strong encouragement for using something like PBL in our classrooms. Another issue that was present in the less successful schools, and even in some instances the more successful, was that the driving question, which is so essential to the PBL process was constructed solely by teachers, with many constraints being placed upon the scope of the question. Regardless of who generates the question, it can’t be so constrained that outcomes are predetermined, as it was obvious in these schools that it left little scope for the students to develop their own investigative process and artefacts. Successful examples of PBL always included a powerful and driving question that engaged the hearts and minds of the students and teachers. The question was big enough to allow scope for all students and to reach across different key learning areas. The best questions encouraged students to generate even more questions. At Sir Francis Drake High School, one academy made the generation of these questions the basis for their whole teaching and learning program by selecting a moral question such as ‘What does it mean to live a good life?’ This umbrella question then helped in the generation of smaller PBL experiences across all the key learning areas. In the West Bronx, New York City, a new school has been established which prides itself on learning as action and the infusing of technology in learning. Following one cohort of students between classes provided an interesting insight into how the use of technology and its success is heavily dependent upon the pedagogy behind the use of technology. The high level of student engagement when learning experiences rich, real and relevant for them was very clear, but this didn’t occur in every class. Although the students had technology in both classes, the effect of teacher pedagogy was the more deciding factor. In one class the students were investigating a question based in the real world, using technology to support their thinking. Because of its real-world appeal, students were motivated to investigate, record, and report their findings. The teacher had established a good relationship with the students based on mutual respect, and insisted upon high standards of work and encouraged the use of goal-setting to help them work. Students were well behaved, attentive and constantly busy thinking and working. In comparison, this same group of students were unrecognisable in their next class. Although this teacher also used technology, the question and answer format of the class produced students who were disruptive, rude and not engaging in their learning at all. While the topic of the class itself was not boring, this class lacked the real-world appeal of the first as well as a lack of hands-on experience, resulting in a group of children with little motivation and engagement and displaying very disrespectful behaviour. This example makes clear the importance of quality professional development for teachers in all schools and especially those that are trying to implement PBL. An understanding of motivation, questioning, goal-setting, cooperative learning strategies and pedagogy when using technology are essential for implementing PBL with more ease and success. All of the schools visited in the United States had a large amount of time for professional development and planning available to teachers. In fact, the standard practice for many school districts in the United States is a short day which finishes by 1pm every fortnight. What differed was how the schools used this time. In less successful schools, teachers used the time to sit alone or in groups and do lessons plans. More innovative use of this time at other schools saw teachers forming teams from across different key learning areas, developing new questions and project focuses, and reflecting upon and evaluating how current projects are going. At West Bronx Academy for the Future, the school has a ‘developer’ who works with a teacher for 45 minutes a day, observing and then coaching the teacher in ways to infuse technology. This is part of a US program called Teaching Matters. Conclusion This trip gave some very interesting insights into how other teachers are using technology to enhance teaching and learning. This scholarship opportunity was indeed a valuable one that would be of great benefit for any teacher who would like to better their own teaching practises in a given area. Some major disappointments were also seen that could be indicative of the directions schools in NSW may head with new reporting requirements. Currently, I believe Australia is headed in the right direction by embracing new technology while encouraging its mindful use, supported by quality professional development for teachers. Including PBL or even some from of social inquiry in Australian classrooms is a way for us to cater to our 21st century learners even more. The real strength of technology and multimedia in PBL lies in its infusion with the subject curriculum and its genuine use in the production process. It would seem that PBL is not without its problems. Many teachers have tried to implement PBL only to feel frustrated and out of control. I believe that success with PBL greatly depends on the degree to which teachers are prepared to take time to think and plan in a different way and to what extent teachers feel comfortable to release control of knowledge and classroom learning time, taking on a new role as co-learner. Using PBL means teachers not having all the answers and often relying on students and others to have the answer instead. Not being able to know what exactly will happen in every class is something that many teachers have found hard to accept. Success of PBL also seems to depend not on the teacher’s view of a project, but whether the students regard the project as interesting and worthwhile. Other factors include making sure that students have the necessary skills to complete the project or the opportunity to develop the skills during the project. Teachers also need to embrace instructional strategies that are more conducive to PBL (hypothesis generation, prediction-making, problem-solving). PBL also seems to work better in a classroom environment when students are focused on learning as opposed to grades and competition, which considering the pressure to assess and report, can be difficult. Introducing and implementing PBL in more traditional school settings will be a challenge requiring a change in teachers’ approaches to teaching and students’ approaches to learning. These changes will require support and resources designed for Australian education settings that provide some of the theory, thinking and structures necessary to help with the successful implementation of PBL. Resources Blumenfeld, P., Soloway, E., Marx, R.A., et al. ‘Motivating Project Based Learning: Sustaining the Doing, Supporting the Learner,’ Educational Psychologist, vol. 26, 3–4, 369–398, 1991. Houghton Mifflin College, Project Based Learning Space, http://college.hmco.com/education/pbl/index.html The 2learn.ca Education Society, http://www.2learn.ca/projects/together/KWORDS/projecta.html Schools mentioned in report Harrison Middle School, Yarmouth, MA, http://hms.yarmouth.k12.me.us/Pages/index Mount Diablo High School, Concord, CA, http://www.mdusd.k12.ca.us/mountdiablohigh/ Newsome Park Elementary School, Newport News, VA, http://npes.nn.k12.va.us/ Sir Francis Drake High School, San Anselmo, CA, http://drake.marin.k12.ca.us/ West Bronx Academy for the Future, Bronx, NY, http://www.bronxacademy.org/west/cms/ Endnote If you wish to know more about the focus of this study or to ask a question, please contact Kathryn Burke by phone during school hours at (02) 9489 7000, or by email at kburke@olorwaitara.dbb.catholic.edu.au For more information about project-based learning and its implication for teaching and learning in 21st century Australian schools, visit www.pblaustralia.com where a collection of ideas, articles and links are being constructed as a result of this scholarship.