Constitutional Protections Accorded Speech

advertisement

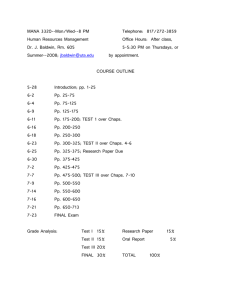

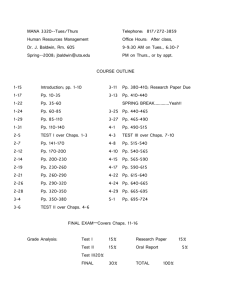

Page 1 53 of 100 DOCUMENTS Texas Torts and Remedies Copyright 2009, Matthew Bender & Company, Inc., a member of the LexisNexis Group. VI. INTENTIONAL TORTS CHAPTER 52 DEFAMATION 4-52 Texas Torts and Remedies § 52.07 AUTHOR: Sharon L. Michaels § 52.07 Constitutional Protections Accorded Speech [1] Public Officials [a] Actual Malice Required The First Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits a public official from recovering damages for defamation relating to official conduct unless the defamatory communication was made with "actual malice." This rule was first stated by the United States Supreme Court with regard to media defendants.n1 It was later extended by the Texas Supreme Court to apply to defamation suits by public officials against private defendants.n2 The rule applies only when the alleged defamation relates to the public official's official conduct or fitness for office.n3 Actual malice must be established independently for each defendant.n3.1 Actual malice must be established by clear and convincing evidence.n4 "Clear and convincing" evidence is defined as "that measure or degree of proof which will produce in the mind of the trier of fact a firm belief or conviction as to the truth of the allegations sought to be established."n5 However, this standard does not apply to evidence of actual malice at the summary judgment stage of a defamation proceeding.n6 [b] "Public Official" Defined All elected officials and employees of government agencies and candidates for elected office appear to be public officials for purposes of the actual malice requirement.n7 Individual states have generally made case-by-case determinations as to whether an unelected public official or employee has sufficient responsibility for or control of governmental affairs to be considered a public official.n8 At a minimum, "public officials" include "those among the hierarchy of government employees who have, or appear to the public to have, substantial responsibility for or control over the conduct of governmental affairs." In addition, if a position in government "has such apparent importance that the public has an independent interest in the qualifications and performance of the person who holds it, beyond the general public interest in the qualifications and performance of all government employees, the persons who hold the position may be considered public officials."n9 A person may be considered a public official even if the person does not hold government office and is not paid by the government if the person meets the other criteria.n10 People holding many different types of positions have been held to be public officials. Law enforcement personnel are "almost universally" held to be public officials.n11 In addition, the following have all been ruled to be public officials: a mayor,n12 a county surveyor,n13 a head football coach/athletic director/classroom teacher at a public high school,n14 a child protective services specialist,n15 an assistant U.S. attorney,n16 a county commissioner,n17 a state district judge,n17.1 a deputy sheriff,n18 an assistant superintendent for business services of a public school district,n19 and a Page 2 4-52 Texas Torts and Remedies § 52.07 court-appointed psychologist.n20 On the other hand, court reportersn21 and school teachersn22 have been held not to be public officials. [c] "Actual Malice" Defined "Actual malice" in a defamation case is a term of art. Unlike common-law malice, it does not include ill-will, spite, or evil motive. Rather, to establish actual malice, a plaintiff must prove that the defendant made the defamatory statement with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was true or not.n23 The standards for proving actual malice are heightened when the complained-of speech bears directly on a political candidate's fitness and qualifications for office.n24 In examining the state of mind of a defendant, the evidence must be viewed in its entirety.n24.1 Hence, the defendant in a defamation case involving a public official cannot "insure a favorable verdict" by testifying as to the sincerity of his belief; ultimately, the defendant's good faith is for the trier of fact to decide.n24.2 To satisfy the burden of proving actual malice by showing the defendant's reckless disregard concerning the truth or falsity of a statement, the evidence must permit the conclusion that, prior to publication, the defendant in fact entertained serious doubts as to the truth of the matter.n25 For example, evidence that a reporter may have fabricated facts or improperly extrapolated them from other facts to create the statistics used in a report raised an issue as to whether the reporter acted with reckless disregard.n26 The standard is a subjective one.n27 Reckless conduct is not measured by whether a reasonably prudent person would have published. Reckless disregard of the truth cannot be established by a mere failure to verify or investigate the accuracy of the statementn28 or the credibility of a source.n29 On the other hand, evidence that the defendant purposely avoided the truth would be some evidence that the defendant doubted the truth of the publication and acted with reckless disregard.n30 The focus of the actual malice inquiry is thus "the defendant's state of mind during the editorial process," and so events outside of that process are of limited value.n30.1 Malice may not be inferred from the falsity of the statement, negligence, or failure to act as a reasonable, prudent person.n31 The actual malice standard focuses on the defendant's attitude toward the truth of what it reported.n32 The trier of fact must determine the defendant's state of mind at the time of the publication; internal inconsistencies in the statements in question, standing alone, do not establish actual malice.n33 Nor may malice be inferred from the mere fact that a source in misquoted.n34 Ill will is not enough, by itself, to establish malice, but may be useful as evidence of the defendant's state of mind to show that the defendant published the information knowing of its falsity or with reckless disregard for its truth.n35 Malice may not be inferred from the mere frequency of a publisher's criticism of a public official's performance.n36 A decision to exclude certain information favorable to the plaintiff is a protected exercise of editorial control and judgment, not evidence of actual malice, although a broadcaster's omission of facts may be actionable if it so distorts the viewers' perception that they receive a substantially false impression of the event.n37 Similarly, although evidence of editorial pressure to produce a sensational story without regard for its truth would raise a fact question as to actual malice, mere evidence of editorial pressure to produce stories from a particular point of view, even when they are hard-hitting or sensationalistic, is not evidence of actual malice.n38 Finally, drawing an erroneous conclusion from the available facts does not necessarily indicate malice.n39 Satire and parody, while constitutionally protected speech, requires a modified application of the actual malice standard, since it often involves presentation of fiction as fact. In such a case, the reviewing court must consider whether a publisher of satire or parody either knew or had reckless disregard for whether the article could reasonably be interpreted as stating actual facts.n39.0.1 In applying this standard, the Texas Supreme Court found, for example, that a satirical article could not be understood as a depiction of actual facts when the article itself contained obvious clues, the article commented on a then-current controversy, the publication regularly published satire and the publication itself adopted a generally irreverent tone.n39.0.2 When coupled with affidavits from the publisher and authors of the piece detailing their states of mind and the steps taken to ensure that the article was understood to be fiction, the Court found that actual malice was negated as a matter of law.n39.0.3 Similarly, when a speaker's statements are summarized or edited by a news organization, the Supreme Court has focused on whether a reasonable reader would have been misled by the alteration. The Court found that, in order to constitute evidence of actual malice, a plaintiff must show that a reasonable reader would have believed the altered passage to be the speaker's actual words and the change to what was actually said must have been materi- Page 3 4-52 Texas Torts and Remedies § 52.07 al.n39.0.4 Thus when a newspaper attributed racially insensitive remarks to a candidate for sheriff, and the candidate denied that he made those remarks, the Court found that a reasonable reader would have realized that the newspaper was paraphrasing or interpreting the candidate's remarks. The alteration was therefore no evidence of actual malice.n39.0.5 The jury's verdict must withstand a further "independent review" by an appellate court to ensure that the verdict comports with the requirements of the First Amendment. This review is not as deferential as the normal appellate review; deference to the judgment of the finder of fact is more limited.n39.1 This "independent review" is accomplished by a three-step analysis. First, the reviewing court must determine what facts were rejected by the jury. Next, the court must determine what facts were established conclusively at trial. Finally, the court must determine whether the undisputed evidence, along with any other evidence the jury could have believed, provides clear and convincing proof of actual malice.n39.2 Evidence that a statement was made maliciously is not negated by an apology to the plaintiff.n40 On the other hand, a refusal to print a retraction can lend support to a claim of malice. However, such a refusal is not, by itself, clear and convincing evidence of actual malice.n41 The defendant may negate actual malice as a matter of law on the basis of a personal affidavit attesting to the absence of malicious intent in making the allegedly defamatory statements. Such an affidavit will support a summary judgment if it is uncontroverted, clear, credible, and free from inconsistencies.n42 Such an affidavit is not controlling, however, as actual malice must be determined from an examination of the totality of the evidence.n42.1 In contrast, expert testimony is not probative on the issue of actual malice. Such testimony is objective and relates to the defendant's reckless disregard for a standard of objectivity. It does not address the subjective truth of whether the defendant entertained serious doubts as to the accuracy of a statement.n43 [2] Public Figures The United States Supreme Court has held that the actual malice requirementn44 extends to suits against media defendants alleging defamation of public figures.n45 Subsequently, the Texas Supreme Court extended this requirement to defamation suits by public figures and public officials against nonmedia defendants.n46 Thus, a defamation plaintiff who is a public figure must offer clear and convincing proof of actual malice, i.e., that the defendant made the allegedly defamatory publication either with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard of the truth such that the publisher entertained serious doubts of the article's truth or acted with a high degree of awareness of the article's probable falsity.n47 In Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc.,n48 the United States Supreme Court clearly delineated the kind of public involvement that makes an individual a "public figure." The Court stated two alternative bases for finding that a person is a "public figure": (1) an individual achieves so much fame or notoriety that he or she becomes a public figure for all purposes and in all contexts; or, more commonly, (2) an individual voluntarily injects himself or herself, or is drawn, into a particular public controversy and becomes a public figure for a limited range of issues. Thus, whether the plaintiff is a "public figure" presents a two-fold question: is he or she a public figure for all purposes or, if not, is the plaintiff a public figure for the issues discussed in the allegedly defamatory communication?n49 Whether a person is a public figure is a question of constitutional law for the court to decide.n50 A "general purpose" public figure is a person who has achieved so much fame or notoriety that he or she is a public figure for all purposes and in all contexts.n51 These people have assumed so prominent a role in the affairs of society that they have become celebrities. Clear evidence of general fame or notoriety in the community and pervasive involvement in the affairs of society are required to establish that a person is a "general purpose" public figure.n52 A "limited purpose" public figure is a person who has voluntarily injected himself or herself, or has been drawn, into a particular public controversy. There is a three-part test for determining if a plaintiff is a limited purpose public figure:n53 Page 4 4-52 Texas Torts and Remedies § 52.07 (1) the controversy at issue must be public both in the sense that people are discussing it and people other than the immediate participants in the controversy are likely to feel the impact of its resolution; (2) the plaintiff must have more than a trivial or tangential role in the controversy; and (3) the alleged defamation must be germane to the plaintiff's participation in the controversy. Thus, the inquiry into limited-purpose public figure status focuses not only on the person allegedly defamed, but also on the subject matter of the defamation.n54 In one case, for example, the court reversed a summary judgment in favor of a media defendant because the plaintiff, an attorney who had received some attention in the media prior to the libelous publication, (1) did not have the high profile that attends a celebrity whose every statement and action is followed with great interest by the public, and (2) had not sought publicity concerning the issue that was the subject of the defamation suit.n55 In another case, a losing candidate for public office was held to be a limited-purpose public figure by virtue of his status as a candidate. By running for office, the plaintiff had thrust himself into the vortex of a public issue (the election). Even though the alleged libel took place after the election and did not directly concern his candidacy, the court held that anything that might touch on a candidate's fitness for office was a matter of public concern vital to the system of democratic elections.n56 In another case, a restaurateur was held to be a limited-purpose public figure when a newspaper wrote an article about his business dealings and prior divorce. The plaintiff had often appeared in advertising for his restaurants, featuring his family, and his business controversies had often appeared in news reports. The court found that because plaintiff sought to promote his "family-man image," and because the continuing media coverage showed substantial public interest in his family and business affairs, plaintiff would be treated as a limited-purpose public figure.n56.1 Emergency medical flight pilots have been held to be "limited-purpose" public figures with respect to the public controversy concerning the safety of emergency medical flight services because they inject themselves into the public controversy.n57 Journalists, reporters, and others who regularly comment on public affairs have often been considered public figures.n58 The Texas Supreme Court has not yet decided whether a plaintiff who was drawn into a controversy involuntarily can be categorized as a limited-purpose public figure.n59 However, the Court did indicate that in determining whether the plaintiff had more than a trivial or tangential role in the controversy, a court may consider whether the plaintiff (1) actually sought publicity surrounding the controversy, (2) had access to the media, and (3) voluntarily engaged in activities that necessarily involved the risk of increased exposure and injury to reputation. Thus, the Court concluded that a reporter who reported live from the grounds of the Branch Davidian compound during the failed Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms raid in 1993 and afterward spoke to the press about the attempted raid and his role in it was a limited-purpose public figure with respect to the raid.n60 On the other hand, relying on the United States Supreme Court's description of a limited purpose public figure as one who voluntarily injects himself or herself, or is drawn, into a particular controversy,n61 the San Antonio Court of Appeals has held that a doctor about whose practice 24 negative articles had been written was a limited purpose public figure because he was drawn into controversy, even if involuntarily.n62 [3] Private Figures In Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc.,n63 the United States Supreme Court held that a newspaper or other media defendant publishing defamatory statements about individuals who are neither "public officials" nor "public figures" could not claim a constitutional privilege against liability for their communications. The Court further held that as long as strict liability without fault was not imposed, each state was authorized to define for itself the appropriate degree of fault that would permit recovery by a private individual from a media defendant.n64 When the subject matter of a defamatory communication involves a matter of public concern, presumed or punitive damages still require proof of malice, i.e., knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth.n65 However, if the subject matter does not involve a matter of public concern, the plaintiff need not prove malice to recover presumed damages.n66 In the context of a defamation action, a matter of "public concern" is not simply a matter of interest to the public. Rather, the public controversy must be a real dispute, the outcome of which will affect the general public or some segment of it in an appreciable way. Private concerns do not become public controversies simply because they attract attention.n67 Page 5 4-52 Texas Torts and Remedies § 52.07 Texas has relied on Gertz to permit a "private figure" plaintiff to establish liability on the part of a media defendant by showing simple negligence.n68 A "private figure" plaintiff may establish that the defendant knew or should have known of the falsity of a communication by presenting testimony that the plaintiff never made the statements or admissions attributed in the defamatory publication.n69 Legal Topics: For related research and practice materials, see the following legal topics: Family LawFamily Protection & WelfareChildrenGeneral OverviewReal Property LawConstruction LawGeneral OverviewTortsIntentional TortsDefamationDefensesExaggerations & Imaginative Commentary FOOTNOTES: (n1)Footnote 1. See New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 279-280, 84 S. Ct. 710, 11 L. Ed. 2d 686 (1964) . (n2)Footnote 2. Casso v. Brand, 776 S.W.2d 551, 555-556 (Tex. 1989) (extending actual malice requirement to suits by public officials or public figures against private defendants. One court has found that a governmental unit may not maintain an action for defamation). Port Arthur Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Klein & Assocs. Political Rels., 70 S.W.3d 349, 353 (Tex. App.--Beaumont 2002, denied) . (n3)Footnote 3. Foster v. Laredo Newspapers, 541 S.W.2d 809, 814-815 (Tex. 1976) (actual malice not required because allegedly libelous statements referring to plaintiff's consulting work for county did not relate to his official conduct as county surveyor or his fitness for that office). (n4)Footnote 3.1. Bentley v. Bunton, 94 S.W.3d 561, 596, 45 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 1172 (Tex. 2002) . (n5)Footnote 4. Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 342, 94 S. Ct. 2997, 41 L. Ed. 2d 789 (1974) ; Carr v. Brasher, 776 S.W.2d 567, 571 (Tex. 1989) . (n6)Footnote 5. Huckabee v. Time Warner Entm't Co., 19 S.W.3d 413, 422 (Tex. 2000) (quoted definition described as "vague.") (n7)Footnote 6. Huckabee v. Time Warner Entm't Co., 19 S.W.3d 413, 420-423 (Tex. 2000) . (n8)Footnote 7. See Foster v. Laredo Newspapers, Inc., 541 S.W.2d 809, 814 (Tex. 1976) (candidates for public office and elected officials are all "public officials," including county surveyor who had minimal responsibilities, was paid no salary, and had no staff, although malice requirement did not apply in this case because alleged defamation did not clearly relate to his "official conduct" as county surveyor). (n9)Footnote 8. Rosenblatt v. Baer, 383 U.S. 75, 84, 86 S. Ct. 669, 15 L. Ed. 2d 597 (1966) . (n10)Footnote 9. Rosenblatt v. Baer, 383 U.S. 75, 85-86, 86 S. Ct. 669, 15 L. Ed. 2d 597 (1966) . (n11)Footnote 10. HBO v. Harrison, 983 S.W.2d 31-39 (Tex. App.--Houston [14th Dist.] 1998, no pet.) . (n12)Footnote 11. Hailey v. KTBS, Inc., 935 S.W.2d 857-861 (Tex. App.--Texarkana 1996, no writ) (deputy sheriff was public official). (n13)Footnote 12. Casso v. Brand, 776 S.W.2d 551, 554 (Tex. 1989) . (n14)Footnote 13. Foster v. Laredo Newspapers, Inc., 541 S.W.2d 809, 814 (Tex. 1976) . (n15)Footnote 14. Johnson v. Southwestern Newspapers Corp., 855 S.W.2d 182-187 (Tex. App.--Amarillo 1993, writ denied) . (n16)Footnote 15. Villarreal v. Harte-Hanks Communications, inc., 787 S.W.2d 131-135 (Tex. App.--Corpus Christi 1990, writ denied) (child welfare worker was public official because of her extensive control over lives of families in her caseload and her extensive dealings with public on behalf of state). (n17)Footnote 16. See El Paso Times, Inc. v. Kerr, 706 S.W.2d 797, 798 (Tex. App.--El Paso 1986, writ ref'd n.r.e.) . Page 6 4-52 Texas Torts and Remedies § 52.07 (n18)Footnote 17. Nobles v. Eastland, 678 S.W.2d 253, 255 (Tex. App.--Corpus Christi 1984, writ ref'd n.r.e.) . (n19)Footnote 17.1. Bentley v. Bunton, 94 S.W.3d 561, 581-582 (Tex. 2002) . (n20)Footnote 18. Hailey v. KTBS, Inc., 935 S.W.2d 857, 861 (Tex. App.--Texarkana 1996, no writ) . (n21)Footnote 19. Beck v. Lone Star Broad. Co., 970 S.W.2d 610, 615 (Tex. App.--Tyler 1998, pet. denied) . (n22)Footnote 20. HBO v. Harrison, 983 S.W.2d 31-39 (Tex. App.--Houston [14 Dist.] 1998, no pet.) (court-appointed psychologist who was given power to determine parent's right to visitation was court official). (n23)Footnote 21. Houston Chronicle Pub. Co. v. Stewart, 668 S.W.2d 727, 729 (Tex. App.--Houston [1st Dist.] 1983, dis.) . (n24)Footnote 22. Poe v. San Antonio Express-News Corp., 590 S.W.2d 537, 540 (Tex. Civ. App.--San Antonio 1979, writ ref'd n.r.e.) . (n25)Footnote 23. Huckabee v. Time Warner Entm't Co., 19 S.W.3d 413, 420 (Tex. 2000) ; Casso v. Brand, 776 S.W.2d 551, 558 (Tex. 1989) . (n26)Footnote 24. Dolcefino v. Turner, 987 S.W.2d 100, 110 (Tex. App.--Houston [14th Dist.] 1998) , aff'd on other grounds sub nom. Turner v. KTRK Television, 38 S.W.3d 103 (Tex. 2000) . (n27)Footnote 24.1. Bentley v. Bunton, 94 S.W.3d 561, 595 (Tex. 2002) . (n28)Footnote 24.2. Bentley v. Bunton, 94 S.W.3d 561, 595 (Tex. 2002) . (n29)Footnote 25. St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 U.S. 727, 731, 88 S. Ct. 1323, 20 L. Ed. 2d 262 (1968) ; see Foster v. Upchurch, 624 S.W.2d 564, 566 (Tex. 1981) (plaintiff who merely showed that allegedly defamatory article contained internal inconsistencies failed to prove actual malice, which requires more subjective evidence of defendant's state of mind and editorial process of writing and publication of article. The Court reaffirmed that the mere fact that the defendant made a mistake is insufficient). (n30)Footnote 26. Gaylord Broad. Co. v. Francis, 7 S.W.3d 279, 285 (Tex. App.--Dallas 1999, pet. denied) . (n31)Footnote 27. Morris v. Dallas Morning News, Inc., 934 S.W.2d 410, 420 (Tex. App.--Waco 1996, writ denied) . (n32)Footnote 28. Doubleday & Co., Inc. v. Rogers, 674 S.W.2d 751, 756 (Tex. 1984) . (n33)Footnote 29. Beck v. Lone Star Broad. Co., 970 S.W.2d 610, 617 (Tex. App.--Tyler 1998, pet. denied) ; HBO v. Harrison, 983 S.W.2d 31-39 (Tex. App.--Houston [14th Dist.] 1998, no pet.) (even assuming statements in film were false and defendants were negligent in failing to investigate matter, there was no evidence of malice in absence of evidence defendants disbelieved statements or statements were so improbable that including them amounted to recklessness). (n34)Footnote 30. Harte-Hanks Communications, Inc. v. Connaughton, 491 U.S. 657, 692, 109 S. Ct. 2678, 105 L. Ed. 2d 562 (1989) (newspaper's failure to consult two sources who could have objectively verified story that was based on testimony of single unreliable source was evidence newspaper purposefully avoided learning facts that would have shown story to be false, which suggested newspaper doubted story's accuracy and published it with actual malice); see Huckabee v. Time Warner Entm't Co., 19 S.W.3d 413, 428 (Tex. 2000) (extensive research conducted by producers of television documentary precluded finding of purposeful avoidance). (n35)Footnote 30.1. See Forbes Inc. v. Granada Biosciences, Inc., 124 S.W.3d 167 (Tex. 2003) (in business disparagement case, "date of publication" rule was held inapplicable to the "actual malice" inquiry. Plaintiff allegedly was promised an opportunity to review the article for errors); this promise was made before the publication date. However, the evidence showed that the allegedly defamatory article had been "locked up" and sent to printer prior to that date. The court found that the "actual malice" inquiry focuses on the state of mind during the editorial process; since the process was over when the promise was made, the promise and the date of publication were irrelevant and no evidence of actual malice). (n36)Footnote 31. Ross v. Labatt, 894 S.W.2d 393, 395 (Tex. App.--San Antonio 1994, writ dism'd w.o.j.) . (n37)Footnote 32. WFAA-TV, Inc. v. McLemore, 978 S.W.2d 568, 573 (Tex. 1998) . Page 7 4-52 Texas Torts and Remedies § 52.07 (n38)Footnote 33. Foster v. Upchurch, 624 S.W.2d 564, 566 (Tex. 1981) . (n39)Footnote 34. See San Antonio Exp. News v. Dracos, 922 S.W.2d 242, 256 (Tex. App.--San Antonio 1996, no writ) . (n40)Footnote 35. Town of South Padre Island v. Jacobs, 736 S.W.2d 134, 140 (Tex. App.--Corpus Christi 1986, writ denied) . (n41)Footnote 36. Freedom Communications v. Brand, 907 S.W.2d 614, 620 (Tex. App.--Corpus Christi 1995, no writ) . (n42)Footnote 37. Huckabee v. Time Warner Entm't Co., 19 S.W.3d 413, 425 (Tex. 2000) (editorial choices in television show about Texas family law courts were not evidence of actual malice). (n43)Footnote 38. Huckabee v. Time Warner Entm't Co., 19 S.W.3d 413, 425 (Tex. 2000) . (n44)Footnote 39. Morris v. Dallas Morning News, Inc., 934 S.W.2d 410, 420 (Tex. App.--Waco 1996, writ denied) ). (n45)Footnote 39.0.1. New Times v. Isaacks, 146 S.W.3d 144, 156-157 (Tex. 2004) , cert. denied, 125 S. Ct. 2557, 162 L. Ed. 2d 276, 2005 U.S. LEXIS 4538 (2005) . (n46)Footnote 39.0.2. New Times v. Isaacks, 146 S.W.3d 144, 161 (Tex. 2004) , cert. denied, 125 S. Ct. 2557, 162 L. Ed. 2d 276, 2005 U.S. LEXIS 4538 (2005) . (n47)Footnote 39.0.3. New Times v. Isaacks, 146 S.W.3d 144, 165 (Tex. 2004) , cert. denied, 125 S. Ct. 2557, 162 L. Ed. 2d 276, 2005 U.S. LEXIS 4538 (2005) . (n48)Footnote 39.0.4. Freedom Newspapers of Texas v. Cantu, 168 S.W.3d 847, 854-855 (Tex. 2005) . (n49)Footnote 39.0.5. Freedom Newspapers of Texas v. Cantu, 168 S.W.3d 847, 854-855 (Tex. 2005) . (n50)Footnote 39.1. Bentley v. Bunton, 94 S.W.3d 561 (Tex. 2002) . (n51)Footnote 39.2. Bentley v. Bunton, 94 S.W.3d 561 (Tex. 2002) . (n52)Footnote 40. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Odem, 929 S.W.2d 513-527 (Tex. App.--San Antonio 1996, writ denied) . (n53)Footnote 41. Gonzales v. Hearst Corp., 930 S.W.2d 275, 283 (Tex. App.--Houston [14th Dist.] 1996, no writ) . (n54)Footnote 42. Casso v. Brand, 776 S.W.2d 551, 558 (Tex. 1989) ; Carr v. Brasher, 776 S.W.2d 567, 571 (Tex. 1989) ; see Tex. R. Civ. P.166a(c). (n55)Footnote 42.1. Bentley v. Bunton, 94 S.W.3d 561 (Tex. 2002) . (n56)Footnote 43. Hearst Corp. v. Skeen,159 S.W.3d 633 (Tex.2005) ; Gonzales v. Hearst Corp., 930 S.W.2d 275, 284 (Tex. App.--Houston [14th Dist.] 1996, no writ) . (n57)Footnote 44. See [1], above. (n58)Footnote 45. Curtis Pub. Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130, 155, 87 S. Ct. 1975, 18 L. Ed. 2d 1094 (1967) . (n59)Footnote 46. Casso v. Brand, 776 S.W.2d 551, 555 (Tex. 1989) ; Carr v. Brasher, 776 S.W.2d 567, 570 (Tex. 1989) . (n60)Footnote 47. Casso v. Brand, 776 S.W.2d 551, 557-558 (Tex. 1989) ; Carr v. Brasher, 776 S.W.2d 567, 570-571 (Tex. 1989) . (n61)Footnote 48. Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 351, 94 S. Ct. 2997, 41 L. Ed. 2d 789 (1974) . (n62)Footnote 49. Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S.323, 351, 94 S. Ct. 2997, 41 L. Ed. 2d 789 (1974) . See Durham v. Cannan Communications, 645 S.W.2d 845, 849 (Tex. App.--Amarillo 1982,writ dism'd) . (n63)Footnote 50. WFAA-TV, Inc. v. McLemore, 978 S.W.2d 568, 571 (Tex. 1998) . (n64)Footnote 51. WFAA-TV, Inc. v. McLemore, 978 S.W.2d 568, 571 (Tex. 1998) . Page 8 4-52 Texas Torts and Remedies § 52.07 (n65)Footnote 52. TSM AM-FM TV v. Meca Homes, Inc., 969 S.W.2d 448, 453 (Tex. App.--El Paso 1998, pet. denied) (builders wrongly accused of having illegally built 40-foot wall that collapsed were not general purpose public figures). (n66)Footnote 53. WFAA-TV, Inc. v. McLemore, 978 S.W.2d 568, 571-573 (Tex. 1998) (reporter at Branch Davidian complex was limited purpose public figure). (n67)Footnote 54. TSM AM-FM TV v. Meca Homes, Inc., 969 S.W.2d 448, 453 (Tex. App.--El Paso 1998, pet. denied) (defendants not entitled to summary judgment on ground that builders who were wrongly accused of having illegally built 40-foot wall that collapsed partially into neighbors' property were limited purpose public figures because defendants failed to establish as matter of law that people other than immediate participants in controversy were likely to feel impact of its resolution). (n68)Footnote 55. Durham v. Cannan Communications, 645 S.W.2d 845, 849 (Tex. App.--Amarillo 1982, dis.) . (n69)Footnote 56. Briggs v. Channel 4, KGBT, 739 S.W.2d 377, 379 (Tex. App.--Corpus Christi 1987) , rev'd on other grounds, 759 S.W.2d 939 (Tex. 1988) . (n70)Footnote 56.1. New Times Inc. v. Wamstad, 106 S.W.3d 916, 924-925 (Tex. App.--Dallas 2003, pet. denied) . (n71)Footnote 57. Einhorn v. LaChance, 823 S.W.2d 405, 413 (Tex. App.--Houston [1st Dist.] 1991, writ dism'd w.o.j.) . (n72)Footnote 58. See San Antonio Exp. News v. Dracos, 922 S.W.2d 242, 255 (Tex. App.--San Antonio 1996, no writ) (TV reporter and news commentator is public figure). (n73)Footnote 59. See WFAA-TV, Inc. v. McLemore, 978 S.W.2d 568, 571-572 (Tex. 1998) . (n74)Footnote 60. WFAA-TV, Inc. v. McLemore, 978 S.W.2d 568, 572 (Tex. 1998) . (n75)Footnote 61. See Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 351, 94 S. Ct. 2997, 41 L. Ed. 2d 789 (1974) . (n76)Footnote 62. Swate v. Schiffers, 975 S.W.2d 70, 76 (Tex. App.--San Antonio 1998, pet. denied) . (n77)Footnote 63. Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 94 S. Ct. 2997, 41 L. Ed. 2d 789 (1974) . (n78)Footnote 64. Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 345-346, 94 S. Ct. 2997, 41 L. Ed. 2d 789 (1974) . (n79)Footnote 65. Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 349, 94 S. Ct. 2997, 41 L. Ed. 2d 789 (1974) . (n80)Footnote 66. Dun & Bradstreet v. Greenmoss Builders, 472 U.S. 749, 755, 105 S. Ct. 2939, 86 L. Ed. 2d 593 (1985) . (n81)Footnote 67. TSM AM-FM TV v. Meca Homes, Inc., 969 S.W.2d 448, 454 (Tex. App.--El Paso 1998, pet. denied) (defendants not entitled to summary judgment on ground allegedly defamatory statements were about matters of public concern and no evidence of malice was produced because defendants failed to establish as matter of law that ramifications of resolution of controversy as to whether builders had proper building permits to build allegedly illegal 40-foot wall would be felt by general public or some segment of it in appreciable way). (n82)Footnote 68. See Foster v. Laredo Newspapers, Inc., 541 S.W.2d 809, 818-819 (Tex. 1976) (actual injuries may be compensated on showing that publisher or broadcaster knew or should have known of communication's falsity); see also Houston Belt & Terminal Ry. Co. v. Wherry, 548 S.W.2d 743, 752 (Tex. Civ. App.--Houston [1st Dist.] 1976, writ ref'd n.r.e.) ; Doe v. Mobile Video Tapes, Inc., 43 S.W.3d 40, 51 (Tex. App.--Corpus Christi 2001, no pet.) (in private plaintiffs' suit against television station, trial court abused discretion by refusing to instruct jury on negligence standard of liability for defamation, but error was harmless). (n83)Footnote 69. Houston Chronicle Pub. Co. v. Stewart, 668 S.W.2d 727, 730 (Tex. App.Houston [1st Dist.] 1983, writ dism'd w.o.j.) (defendant knew or should have known that defamatory statement about private-figure court reporter was false in light of third party's testimony that reporter never made statement attributed to him).