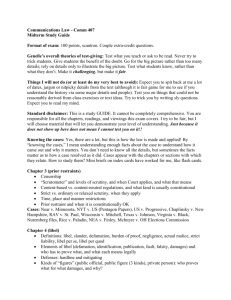

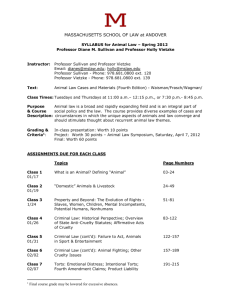

Centuries of Libel Law Erased by Times

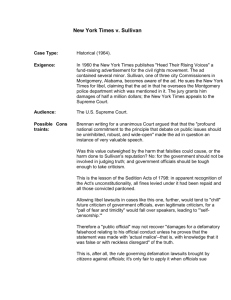

advertisement

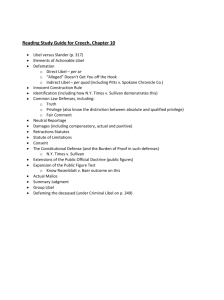

Centuries of Libel Law Erased by Times-Sullivan New York Law Journal January 30, 1984 Mr. Goodale, former vice chairman of The New York Times, is a member of the New York law firm of Debevoise & Plimpton. He was assisted in the preparation of this article by John S. Kiernan, an associate of that firm. Forget libel law for the last 100 years. The only case that counts is Sullivan v. New York Times Co.,1 and that was decided only 20 years ago. With one fell swoop of the pen, the Warren Court overturned centuries of common law and held that the First Amendment applied to the law of libel. Sullivan held narrowly that statements about public officials are constitutionally privileged, even if false, so long as they are published without “actual malice” – that is, knowledge of reckless disregard of their falsity. Its logic extended much further, suggesting that freewheeling public debate is so essential to the First Amendment that the participants in such debate are entitled to extra breathing room, even at the cost of some false statement that causes injury to appropriate targets of the debate. Dean Prosser, who was forced to add an entire chapter to his Torts treatise as a result of the decision, called the decision “unquestionably the greatest victory won by the defendants in the modern history of the law of torts.”2 More was to come. The common law before Sullivan did not give the press much leeway in what it wrote about public officials, or about anyone else. In Alabama, where Sullivan arose, a newspaper was absolutely liable for any false statement, even the result of innocent misstatement that “tend[ed] to injure a person . . . in his reputation: or to “bring him into contempt.”3 Strict liability was nearly the universal rule, endorsed by the Restatement of Torts and by most states.4 The few grumbling dissenters tended only to exonerate 1 376 U.S. 254 (1964). 2 W. Prosser, Torts, Ch. 21, and p. 819 (4th Ed. (1971). 3 376 U.S. at 254. 4 W. Prosser, Torts, Sec. 108 at 791-92 (Bd. Ed. 1964); Restatement, Torts Sec. 582 Comment g (1938); Rosenbloom v. Metromedia, 403 U.S. 29, 87 n. 13 (1971) (Marshall, J., dissenting); Developments in the Law – Defamation, 69 Harv.L.Rev. 875, 902-10 (1956). 50.doc defendants from the results of innocent mistake, not to allow misstatements when any degree of fault was present.5 Aside from the defense of truth, the principal privilege available to publishers of defamatory statements before 1964 was the qualified privilege of “fair comment.” In about three quarters of the states, this privilege was narrow. It meant only that newspapers were free to print defamatory opinions about matters of “public interest” and “public concern,” so long as those opinions did not make or imply any false assertions of fact.6 What constituted the public interest was of course a matter of great dispute, and even statements of opinion without any factual assertions at all were protected only if newsworthy. In a few states, though, the seeds of Sullivan were germinating. Renegate courts were holding, without any reference to the Constitution, that the right of fair comment was so important as to make an occasional false statement of fact excusable in the interest of keeping public debate open.7 Strict Liability Meanwhile, the Constitution lay dormant in defamation actions. In 1909 Oliver Wendell Holmes, writing for a unanimous Court, endorsed the common law rule of strict liability in libel action.8 Although the Supreme Court intimated that the First Amendment applied to the states as early as 1925,9 and firmly declared this in 1931,10 no one made the connection between the First Amendment and the law of libel. In the process of addressing prior restraints of scandalous publications, contempt judgments against critics of a court, “fighting words” statutes and obscenity laws, the Court 5 W. Prosser, Torts, Sec. 108 at 792 n.38 (3d Ed. 1964). 6 Id., Sec. 110, at 814. 7 See cases cited in Sullivan, 376 U.S. at 280 n.20. 8 Peck v. Tribune Co., 214 U.S. 185, 189 (1909). 9 Gitlow v. New York, 263 U.S. 662 (1925). 10 Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 357, 358 (1931). 2 50.doc repeatedly noted in dictum that the Constitution offered no protection to libel defendants.11 Then came Sullivan, a case presenting a perfect opportunity to make new law. Sullivan, a city Commissioner in Montgomery, Alabama, sued The New York Times over a political advertisement purchased by blacks participating in non-violent civil rights demonstrations in the South. The ad asserted among other things that police had ringed a Montgomery college campus where students were demonstrating, had padlocked the college dining hall in an effort to starve the students into submission, and had repeatedly arrested Rev. Martin Luther King. It was accurate in most respects, but contained some false statements. Although the plaintiff was not identified by name anywhere in the ad, an Alabama jury awarded him $500,000 without hearing any evidence of actual injury to his reputation. First Amendment Rights The Supreme Court held without difficulty that the judgment must be reversed because the evidence did not show that the article had defamed the plaintiff. But it did not stop there. After reviewing this country’s long history of opposition to laws restricting free commentary on affairs of government, it held in a broad stroke that the First Amendment prohibits the imposition of liability for defamatory statements involving public officials, even if these statements are negligently false. The Court’s language has been quoted so many times that it is by now familiar. Justice Brennan cited “a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government officials.”12 Absolute liability for false statements would result in self-censorship that was inimical to these goals, the Court reasoned.13 To protect the interests in debate, the press received the protections of a new qualified privilege – the “actual malice” requirement – a new 11 Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697, 715 (1931); Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U.S. 331, 348-49 (1946); Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568, 572 (1942); Times Film Corp. v. City of Chicago, 365 U.S. 43, 48 (1961). 12 376 U.S. at 370. 13 Id. at 270. 3 50.doc standard of proof – “convincing clarity” – and a new standard of judicial review – “independent examination of the who record.”14 Despite the breadth of the Court’s holding, Justices Black and Douglas wrote separately that the Court had not gone far enough, maintaining that all restrictions on the press’s freedom violate the First Amendment,15 and Justice Goldberg wrote that all restrictions on the right to print statements about public officials are unconstitutional.16 Libel law in the 20 years since Sullivan has focused on at least two separate but related issued – first, what Sullivan means and how far it extends; and second, what practical protections are appropriate to secure for the press the protections Sullivan and its progeny are meant to provide. The first area of development, while not settled, has at least stabilized into rules that are familiar to press lawyers. The second is far from such stability. Public Figures It didn’t take long for the Court to begin explaining what Sullivan meant, although the explanation proceeding by fits and starts. Only a few years after it was decided, the Court unsurprisingly announced that despite the opinion’s reliance on the historical legitimacy of criticism of government, its logic applied with equal force to cases involving non-governmental public figures as well.17 Soon after, it explained that to have published with “actual malice” a defendant must have “in fact entertained serious doubt as to the truth of his publication.”18 The Court also addressed the issue of how low a governmental official must be before he is no longer a “public official” within the meaning of Sullivan,19 and for a short time embraced a rule that, like the suddenly obsolete defense of fair comment, focused on the newsworthiness of the subject matter 14 Id. at 286. 15 Id. at 293-97 (Black, J. joined by Douglas, J. concurring. 16 Id. at 297-305 (Goldberg, J., joined by Douglas, J., concurring. 17 Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130 (1967). 18 St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 U.S. 727, 731 (1968). 19 Rosenblatt v. Baer, 383 U.S. 74, 84-86. 4 50.doc rather than the identity of the alleged victim in determining the scope of the constitutional privilege.20 In 1974, the Court attempted to complete the Constitutionalization of libel law that it had begun in Sullivan, in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc.21 Once again, it went far beyond the facts of the case to set down rules that would establish benchmarks for interpreting Sullivan and would extend some constitutional protections into the remaining areas of the common law untouched by the First Amendment. At the outset, the Court rejected the old fair comment approach of assessing a published item’s newsworthiness before deciding how much protection to accord it, expressing the conviction that courts should not find themselves in the business of determining what is or is not newsworthy. As an alternative, the Court returned to its previous scrutiny of the public nature of the alleged victim. It redefined what makes a person a public figure, stating that a person can be an all-purpose public figure or, by injecting himself into a particular controversy, can become a limited purpose or “vortex” public figure.22 Defamatory statement with respect to either type of public figure were deemed privileged. Qualified Fair Common Privilege Next, it laid to rest the last vestiges of the qualified fair comment privilege, with the blanket statement that “[u]nder the First Amendment there is not such thing as a false idea.”23 Opinion need no longer be newsworthy to be constitutionally protected; it is privileged in all cases.24 Finally, it explained how the First Amendment applies to private individuals, holding that the states need not require such individuals to prove “actual malice” but 20 Rosenbloom v. Metromedia, 403 U.S. 29 (1971). 21 418 U.S. 323 (1974). 22 Id at 345. 23 Id at 339. 24 Hotchner v. Castillo-Puche, 551 F.2d 910, 913 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 834 (1977); Rinaldi v.Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Inc., 42 N.Y.2d 369, 380, 397 N.Y.S. 2d 943, 950, cert. denied, 434 U.S. 969 (1977), Cf. Bose v. Consumers Union 692 F.2d 189 (1st Cir.1982), cert. granted, 51 U.S.L.W. 3774 (1983). 5 50.doc cannot impose liability without fault,25 and that punitive damages may not be imposed without a finding of “actual malice.”26 Although uncertainty remains over the limits of Sullivan’s protection, the method of analysis of a libel suit has now been in place without significant change for a full decade. Students of the First Amendment have become comfortable with the notion that the press has substantial protection against libel actions. This notion, however, doesn’t square with the facts. Paradoxically, press defendants are defending more libel actions and being assessed heavier damages than ever occurred before Sullivan. More press self-censorship goes on now, under the careful scrutiny of lawyers, than at any other time in my quarter-century of practice as a press lawyer. Although Sullivan and its progeny provide substantial theoretical protection to the press, and usually end up producing a judgment in the press’s favor at the end of a long litigation, the press rightly feels fully as vulnerable now than it did before Sullivan. There are several good reasons for this sense of vulnerability. The first is a gradual but perceptible shift in public sentiment. Juries in all forms of tort litigation are finding for individual plaintiffs with less attention to the arguments of corporate defendants and greater inclination to award staggering damages than ever before.27 Because the same press that was credited with unraveling the mysteries of Watergate is now widely viewed as arrogant and over-intrusive, jury sympathy has often ranged against it with special intensity. Second, the pure prospective cost of defending a libel suit is the greatest source of self-censorship.28 This cost can take many forms: hundred of thousands of dollars in legal fees; intrusive examination into areas of decisionmaking once thought to be within the realm of protected editorial privilege;29 attempts to compel identification of 25 418 U.S. at 347. See, e.g., Chapadeau v. Utica Observer-Dispatch, Inc., 38 N.Y.2d 196, 379 N.Y.S.2d 61(1975) (private figure may establish liability only by showing that “the publisher acted in a grossly irresponsible manner without due consideration for the standards of information gathering and dissemination ordinarily followed by responsible parties.”). 26 Id. at 350. 27 See Libel Defense Resource Center Bulletin, No. 6, at 2 (Winter 1982). 28 See Anderson, Libel and Press Self-Censorship, 53 Tex.L.Rev. 422 (1975). 29 See Herbert v. Lando, 441 U.S. 153 (1979). 6 50.doc confidential sources;30 and the pressure, frustration and demands on personal resources of defending a nagging litigation for half a decade or more before its resolution. Some courts have combatted these trends with increased sensitivity to the appropriateness of summary judgment in libel actions.31 Others have conducted intrusive reviews of trial records, leading to an increasing rate of judgments notwithstanding the verdict and reversals on appeal.32 Still others, together with press scholars, have attempted to cut back on the damages a jury can award, eliminate punitive damages altogether,33 and retain substantial protection for journalists’ promises of confidentiality to sources.34 This new level of practical protections is in its relative infancy. Without these protections, the robust debate envisioned by Sullivan is dangerously circumscribed. In spite of all that Sullivan and its progeny accomplished, in the current litigation environment, the spectre of monumental liability for a small slip-up looms more heavily over editors’ rooms today than it did 20 years ago, leading to unilateral deletion of many of the precise statements, opinions, paragraphs, and articles that Sullivan intended to foster. 30 See, e.g. Bruno & Stillman, Inc. v. Globe Newspaper Co., 633 F.2d 583 (1st Cir. 1980). 31 Compare Rinaldi v. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, supra, 42 N.Y.2d at 384 (favoring summary judgment) with Hutchinson v. Proxmire, 443 U.S. 111, 120 n.9 (1979) (disfavoring it). 32 See Libel Defense Resource Center Bulletin, No. 7, at 21 (Spring-Summer 1983). 33 See generally Goodale, The Burnett Case. The New York Times, at A23 (April 9, 1981). 34 See, e.g., Miller v. Transamerica Press, Inc., 628 F.2d 1932 (5th Cir. 1980); Bruno & Stillman, Inc. v. Globe Newspaper Co., 633 F.2d 583 (1st Cir. 1980); Cervantes v. Time, Inc., 464 F.2d 986 (8th Cir. 1972). 7 50.doc