PF 13_Yale JLHuman - Teachers Discovering History As

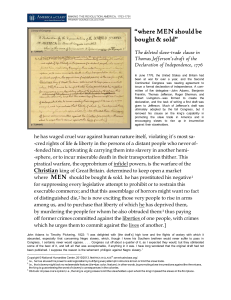

advertisement