Memory

advertisement

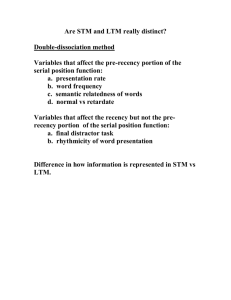

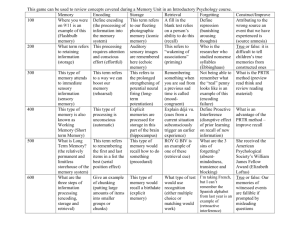

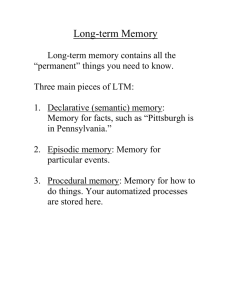

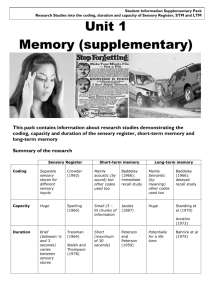

Memory Mind Map of this page. Introduction Human Memory is a complicated system for storing and retrieving vast amounts of various types of information. There is some disagreement as to the precise nature of the human memory system, however most experts accept a distinction between sensory memory, short term memory (STM) and long term memory (LTM) Sensory memory is a system for retaining a brief impression of a sensory stimulus after the stimulus has ceased. It is also characterised by being outside of conscious control (i.e. it happens automatically and unbidden). The duration of sensory memory varies for each of the senses, although it is generally said to be under a second. The purpose of sensory memory is to help people make initial subconscious assessment and judgement of sensory stimuli. Sensory memory is evident when we view a person moving on television; we perceive him or her moving quite normally. However the information that is presented to us is a series of frozen images (frames) separated by brief periods of darkness. In order to see the moving image, it is necessary for the brain to store visual information from one frame until the arrival of the next (Baddeley, 1999). Auditory sensory memory works in the same way. If a person hears the word “dyslexia” their sensory memory stores the “dys” and the “lex” sound until the end of the word after the “ia” sound is made in order for us to hear it as a single word. Short term memory (STM) is a store of limited size and duration. It is used for more advanced processing then sensory memory and is generally said be a conscious memory system. I.e. we are aware when we are using it and often have control over what we use it for. In 1974 Baddeley and Hitch developed the model of STM into a slightly more complicated model which they called working memory. Despite this more recent development the fundamental principles remain the same. It can hold about seven meaningful bits of data such as words or numbers. It only stores information for a limited amount of time (between several seconds and a minute) It is a gateway to the long term memory store. It can use information from LTM to help in completing and understanding tasks. STM is used for many simple tasks that encompass day to day life, and is required for us to work things out and understand them. For example if you read or hear a sentence, you need to remember the beginning until you get to the end in order to make any sense of it, or if someone asks you to divide 212 by 4 you need to remember the two sets of numbers, the order that they appear and that you have to divide them in order to complete the sum. Both of these procedures require information from long term memory such as how to read the words in the sentence, the meaning of the words in the sentence, the structure of numbers and how to divide them. Short term memory only holds data for a limited period of time. This is demonstrated in the following experiment. Read the following set of numbers a couple of times… 3489243 …and then turn away and write them down (without looking back at the set). It is likely that someone without any short term memory difficulties would not have too many problems and get most of the numbers correct. However, if you read the following set of numbers a couple of times… 4093217 …and read on for 10 minutes, and then try to write them down, it is not so likely that you would be able to remember them. (Try to remember the numbers after you have read this article) When a task is completed, the information is either lost from STM or it is retained and moved into long term memory system. Long term memory is a store of arguably limitless capacity and duration. Long term memory is like a library in which all our knowledge, our memories of past events and of how to do things are stored. Any information that can be remembered for after a period of about a minute would usually be classified as being stored in LTM. This is because memory that is stored for a minute or longer acts in very much the same way as memory that is stored for several days or weeks, and very differently to memory that is stored for several seconds (Baddeley, 1999). Some memory experts argue that LTM has an infinite duration and that forgetting is really an inability to find a particular memory in the store. Other experts say that some memories do actually decay from long term memory and disappear. There are however divisions within the long term memory system. These divisions are categorised by the type of memories that are stored. Episodic long-term memory is a store of particular incidents that happen to an individual, such as going to the supermarket yesterday or watching a film the day before. Semantic long-term memory is a store of knowledge such as knowing that Paris is the Capital city in France, or the number of strings on a classical guitar. How the stores interact. Information impinges upon the senses and sensory memory is at constant work in order for us to group sensory input into simple meaningful forms. If we decide to focus on any of these simple meaningful forms and want to process the information into more complicated meanings, our short term memory takes over. STM provides enough storage for us to focus upon simple tasks, such as listening to and understanding a sentence, or structuring a question to ask somebody. STM also relays information from LTM to further aid this task, such as the meaning of words and the sounds words make. Most information from STM is only required for a small time and is therefore forgotten, however sometimes it is necessary for the information to be held for a longer period. Information of this type is usually rehearsed, analysed or associated with other memories. This moves the information into LTM where it is stored for a longer duration. Information that is in LTM needs to be actively used and rehearsed or it becomes harder to retrieve and can be eventually forgotten. Some neurologically diverse (and neurotypical) students can experience difficulties with memory. When it comes to the collecting, understanding, ordering and remembering the information required by many undergraduate courses, difficulties with memory can affect their ability to carry out the tasks as effectively as they might like. It is however possible to improve our memory by using our understanding of how the memory system works. HOW TO IMPROVE YOUR MEMORY In order for information to get to Long Term Memory (LTM) it has to pass through Short Term Memory (STM). Difficulties with STM can limit the amount and quality of the information that gets into LTM. There are however several conscious strategies that can further enhance this process. Motivation It might seem an obvious point, but we are much more likely to remember if we want to remember. Animal studies have shown that animals learn things better if they are rewarded at the end of it. One of the BRAINHE interviewees who has Asperger Syndrome experienced this and said, ‘Choose a course that you are interested in and not one your parents want you to do.’ If the act of memorising or remembering is just a chore, it will be much more difficult. Most courses contain compulsory modules that you may not find as interesting as the others. Try to imagine how you would feel if you got a good mark in such a module, a good degree or a good job after getting your degree. Why not reward yourself for learning a piece of material with a chocolate bar or by going out for a drink. Rehearsal Rehearsal is required to get information into LTM, and to increase the chances of being able to recall that information. Take the following sentence: “Baddeley and Hitch proposed the model of working memory in the 1970’s” If you were to repeat this sentence continuously for five minutes and did not get confused, you would undoubtedly be able to recall it at the end of the five minute period. However you do not have to constantly rehearse information in order to recall it. There is a method called expanded rehearsal which has a similar effect, and you should be able to recall the information for several days, weeks or even permanently. Keep repeating information, with widening gaps between the repetitions. Every 30 seconds for several minutes, every minute for 10 – 15 minutes, every five minutes for an hour, every 15 minutes for 2 hours, every 30 minutes for 5 hours, every hour for the rest of the day, then once a day for a while and it be stored to its maximum potential. Chunking To some degree we do this automatically. It is literally a case of chunking several pieces of information into one meaningful chunk, which takes up less space in STM For example 0 1 2 1 3 3 1 5 6 2 3 is not very easy to remember and will probably be forgotten if you don’t write it down. However if you put the information into chunks as follows it becomes a bit easier: (0121) the Birmingham code (331) (56) (23) You don’t have to divide the information into the same chunks as above. You can split it up in any way you want. Phone numbers in France are usually broken up into pairs. You could therefore split the number up like this and use the French way (zero-one) (twenty-one) (thirty-three) (fifteen) (sixty-two) (three) Chanting the Rhythm To make the number or sentence even easier to recall you could rehearse it by chanting the numbers or the chunks to make a sort of rhythm. This can also be applied to words, sentences or whatever information you want to store. Names and Faces Names and faces can difficult to code. They are difficult to rehearse. Look out for unusual names, which maybe easier to remember. There are lots of special techniques for remembering names but they often involve hearing the name properly in the first place and then coding it. Try repeating somebody's name and say it a couple of times. Try to associate someone’s name with one of their features. For example Billy might have Blue eyes: Billy Blue eyes. Visualisation and Association Many neurologically diverse people, especially dyslexic people, have strong visual abilities. Visual images can be very powerful memory cues. If we visualise in detail where we were when we first learnt a piece of information, it can be easier to recall it. It is often a good idea to make a mental note of the environment that you are in whilst you learn something. Many people find that making a mental visualisation of numbers, words or other information whilst learning helps them to recall it more effectively. For Example You could see a telephone number or chunks of a telephone number in your mind. Imagine them as a set of decorative house numbers that appear on doors, or imagine them in a style of text that you like. You could even remember a phone number by associating each number or chunk with sections of a route or rooms in a house that you know well. This method is known as the Greek walk. It is a technique which involves remembering the various places in a route, house, room or an environment with which you are familiar and then placing what you want to remember within those locations. For instance, if I memorise the rooms in my parent’s house I can easily have 19 places in which to put objects I wish to remember. Tell a Story. Remember a sequence of items by telling a story. This involves a narrative, in which strange and bizarre things are linked together. These work best if there is much colour, action, humour, movement, sound, sex-- involve all the senses. For more complicated information such as a piece of text it is a good Idea to convert it into diagrammatic from such as a spider diagram or flow chart of the main points and try to remember that. The best way to do this is to go through the piece of text highlighting the main points. Summarise these main points and write them down. Put these points into a diagram, using the diagrammatical structure to show the relationship between the main points. This method takes some practise but it can really help aid recall. It is often helpful to associate new information with other memories that you have in long term memory. For example the phone number referred to previously 01213315623 could be associated with information already in LTM: (0121) – dialling code for Birmingham 33 – my age 15 – Andy Warhol quote "In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes." 6 – part of my date of birth 6th Feb 23 – Beckham’s Real Madrid number It is also important to take some time remembering the order of the associations. (Birmingham) (age) (Warhol) (birthday) (Beckham) The fact that you spent some time relating the information to other memories is also likely to help you remember it, as deeper levels of processing aid better recall. It seems that the more associations that are made between the information and what the person already knows, the more the person will be able to recall at a later date. Peg lists. In his book on memory, Speed memory, Tony Buzan was very keen on linking numbers with other visual memories as follows: The number rhyme system. one = bun two = shoe three = tree four = door five = hive six = sticks seven = heaven eight = gate nine = wine ten = hen If you memorise the rhyming words for each number, it becomes easier to remember numerical lists of up to ten items. If you needed to remember the following list 1 Bag 2 Tomatoes 3 Chair 4 Bed 5 Donkey You would then assign the list to the appropriate rhyming words and try to make a visual link: 1 = bun + Bag: A big bag of buns 2 = shoe + tomatoes: Someone squashing a tomato with their shoe 3 = tree + chair: A chair made out of wood from a tree. Another way of using this system is for remembering numbers. So if I wanted to remember that Malcolm lived number 49, I would imagine going up to Malcolm’s front door and then noticing a huge bottle of wine leaning against it! If I wanted to remember the first part of my son's phone number 325, I could remember the tree with a shoe on it, and precariously balanced on top of that shoes is a hive, just about to fall off, with who knows what scary consequences! Using your fingers The process of assigning a series of words or numbers to your fingers can help you to remember them. This is usually done by assigning one word or number to each finger The motions made by the fingers activate neural pathways in the brain. The brain associates these pathways with the words or numbers you are trying to remember. The process of repeating the motions again at a later time often helps recall the information. Remembering numbers, formulae, dates chunk them down into small units visualise numbers use specific rehearsal techniques for numbers e.g. Buzan write them down store them on a mobile phone Retrieving information from LTM Long term memory holds a colossal amount of information. Your whole life so far and everything you know are all stored in long term memory. All the words you know and all the abilities you have such as riding a bicycle are stored. Whilst individuals may not be able to recall a particular event at a particular moment, we are often able to recall the event at a different moment. We therefore have a lot more stored in our long term memory than we can recall at any particular instance. Long term memory has often been likened to a vast library. To access memories efficiently from LTM the information needs to be stored in a structured and accessible way. If the books in the library were catalogued by the colour of the cover, the library would be relatively useless if someone were looking for a book on Web technology. However if the books were catalogued by the subject index then the information would be easier to find. If someone wanted a book they had used before about web technology but could not remember its name, however they managed to remember that it was a blue book, then combining the subject index with the book colour would give them a greater chance of finding it than just using the subject index itself. This is why the more associations a memory has the easier it is to retrieve. The multisensory approach. One of the strongest ways of retrieving memories is by using a multisensory approach. Smells, tastes and movements are particularly powerful sources of recollection for many people. If you learnt a piece of information whilst sucking a strawberry sweet, why not suck another strawberry sweet whilst trying to remember it. You could have a whole range of different flavoured sweets for different pieces of information. This method could also work with smells and movements. Why not revise for an exam a spray some perfume in the room you are revising in. When it comes to the exam take in a handkerchief with the same perfume sprayed on it and sniff it when you need to recall the information. The tip of the tongue phenomenon Occasionally we are asked a question where we are sure we know the answer but we are unable to access it. This answer is often said to be on the tip of the tongue. Several experiments including Brown and McNeil (1966) have indicated that there are several methods we can use to help us when this happens: Guess the number of syllables in the word you are trying to find. It is often the case that when the tip of the tongue phenomenon arises people actually remember aspects of the word but not the word itself. People often guess the number of syllables correctly. Try working through the alphabet to connect with the word you have lost. Studies have shown that if a person is given the first letter of the answer, they are more likely to remember it. Look for the context of what you know about that word. Visualise that context as much as possible, making it colourful, full of movement and sound. If it's a person’s name, visualise them as accurately as you can. Think of them with other people and in numerous situations. If you still cannot remember the word, just relax and it will come before too long. Finding your way Try to obtain a map or a plan of where you are going. Study the map and plan the route you need to take. Try to remember key items from the map, such as street names or other land marks. Circle the place you want to get to on the map and keep the map with you. Write down the route step-by-step using street names, landmarks and navigational directions. If it is realistic, save up for a sat nav! Revising for Exams There are many techniques for enhancing memory for revision and exams. Please click here for the BRAINHE exams and revision section. Daily ways of improving memory A sharp mind and strong memory depend on the vitality of your brain's network of interconnecting neurons, and especially on junctions between these neurons called synapses. (http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=60455) Therefore keeping the brain healthy is likely to keep memory healthy. Reduce stress. Stress is a main cause of synaptic dysfunction. When stressed, we produce too much glutamate which can become a toxin at high levels, and interfere with learning and cause cell damage in the brain's memory regions. Make time for leisure activities. Learn relaxation techniques such as yoga or meditation. Cut down on unnecessary responsibilities and avoid over-scheduling. Become more organised and stick to a routine. Whilst routine is important in reducing stress, it is also important to enjoy new sensory experiences and to challenge your mind and body with new situations. This helps to keep the brain healthy by creating new neural connections. Exercise: A brisk walk or other cardiovascular workout oxygenates the brain and promotes brain growth factors. It is essential to get plenty of adequate sleep and rest. Adequate sleep reduces stress and new brain cells grow as we sleep. What you eat can improve your memory (http://www.helpguide.org/life/improving_memory.htm) Antioxidants and vitamin A are key brain boosters, because they improve the flow of oxygen through the body by fighting free radicals, strengthen blood circulation and combat fatigue. Good foods for memory boosting are blackcurrants, blueberries, watermelon, strawberries, cherries, asparagus, red cabbage and tomatoes. Constant daily training will improve memory:; for instance: Make a point of listening to people’s names and repeating them to yourself. Put essential items at home in the same place each day e.g. keys. This takes the burden off the memory system by trying to remember things that are unnecessary. Keep a diary or personal organiser and regularly fill it in. The process of writing things down can help you to remember by using deeper levels of processing. Keeping organised gives you a framework to relate to when trying to remember. If your memory is usually quite poor . . . Have a notebook and write things down Keep items in a special place e.g. keys, purse, wallet use a wall chart and diary Also keep a personal diary to write down daily events after they've happened Make plenty of lists. Consider using Web-based systems such as Tada, backpack etc Keep noting your ideas, either with a notebook or a tape recorder or MP3 player. If you take medication, use standardised medicine boxes Improve your memory through playing games, crosswords, mind games with yourself (for instance try counting down from a hundred in 2s, 3s, 4s, etc, as fast as you can) Bibliography Baddeley, A.D., (1999). Essentials of Human Memory., Psychology Press: East Sussex Baddeley, A.D., (1974). Working Memory. In G.A. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of Learning and Motivation (pp.47-89). Acedemic Press : New York Bartlett, D., & Moody, M., (2000) Dyslexia in the workplace., Whurr Publishers: London BBC Bite size. (2007). Mind maps revision techniques, Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/teachers/supportingstudentsrev4.s html [ Accessed 4 February 2007]. Buzan, T. (2006). Brilliant memory. BBC books. Goodwin, V. & Thomas, B. (2004) Making Dyslexia Work for You., David Fulton Publishers: London. Iddon, Jo and Williams, Huw. (2005). Memory Boosters. Hamlyn. ISBN 0 600 61324 0. Medical News Today, Want to improve Your Memory? , 11 Jan 2007 http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=60455 Myers, D.G. (1998). Psychology 5th ed, Worth Publishers: New York Stein, J. (2007 ). 30 ways to improve your memory/Independent newspaper. [ Double Your Brain Power Supplement . 30 ways to improve your memory, by Rita Carter and John Stein. A3 leaflet ]. Ta-da lists. (2007). Homepage .Available from: www.tadalist.com/ [Accessed 4 February 2007]. External links about memory and learning