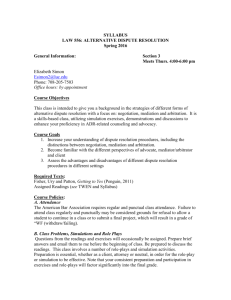

07.798 (A00) Negotiation and Alternative Dispute

advertisement

Faculty of Education Graduate Studies & Field Research 07.798 (A00) Negotiations and Alternative Dispute Resolution: Theory and Practice Summer / 2011 / Term B Dates: July 4 - 8, 2011 (on-campus) Time: 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Location: Education Building, room #203 Instructor Name: Professor Alan Levy Office #: Clark Hall, room #404 Telephone: (204) 727-9708 Email: levya@brandonu.ca Course Description: This course addresses Negotiations & Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) in the workplace, including theoretical models and applications relevant to managing conflict in employment settings. As well this course is designed to provide theoretical knowledge and practical skills essential to being effective negotiators in an educational workplace framework. Education theory and models will be closely examined concerning conflict resolution. Participants will learn successful strategies for negotiation, as well as have ample opportunity to practice their skills in simulation exercises. The program offers a systematic approach to mastering the fundamentals of making favorable agreements that minimize conflict and maximize results. Some specific benefits include: (1) learning how to maximize the potential of making an agreement on your terms; (2) learning how to avoid making an unfavorable agreement; (3) identifying strengths and weaknesses in personal negotiating style; (4) improving your ability to make good choices in negotiation strategy; and (5) understanding the role of relationships in making good agreements. Instructor presentations, readings, simulations, case studies and research projects will acquaint students with the advantages and disadvantages of ADR. Students will gain a firm understanding of how to resolve workplace conflict in both unionized and nonunionized environments. Negotiation is the science of securing agreements between two or more interdependent parties. The central issues of this course deal with understanding the behaviour of individuals, groups, and organizations in the context of competitive situations. The course is intended to help you: • To understand and think about the nature of negotiation and work-place conflict. This objective is paramount because many of the important phenomena in negotiation (such as interests, goals, and cooperation) are ambiguous and often do not have "right" answers - we cannot teach a set of formulae that will always maximize your profit (although they might help). • To gain a broad, intellectual understanding of the central concepts in negotiation and conflict resolution. These concepts will be the building blocks from which we can systematically understand and evaluate a negotiation and conflict resolution process. • To develop confidence in the dispute resolution process as an effective means for resolving conflict in organizations. • To improve analytical abilities in understanding the behaviour of individuals, groups, and organizations in competitive situations. • To provide experience in the dispute resolution process, including learning to evaluate the costs and benefits of alternative actions and how to manage the negotiating process in an educational setting. Course Format Most class meetings will be organized in a seminar style, to facilitate critical analysis of topics considered. Active discussion is encouraged at all times during the course. Therefore, it is the instructor’s responsibility to create an atmosphere that facilitates student participation in the learning experience. It is the student’s responsibility to take advantage of this opportunity to learn, by ensuring that all assigned readings are done. This course is taught in a case study approach, using the pedagogy of action learning thus the course requires self directed learning. In other words, students must manage their own learning development to obtain the highest level of learning satisfaction. There is a high degree of creative learning during the scheduled classes, through initiative methods of teaching. Learning Objectives This course is designed to launch you on a career-long path of critical thinking and reflection as a conflict intervener and practitioner. A list of life-long learning objectives in peace and conflict includes: • Articulating and questioning how your view of reality, human nature, the meaning of life, conflict, change, and human relationships guide and shape conflict behaviour and work; • Understanding how and why conflict occurs in education settings and through communication for ourselves and those with whom we engage; • Developing a critical understanding of major assumptions and premises of conflict models and theories; • Applying theoretical tools to specific conflict situations to reveal assumptions and beliefs about current intervention strategies of conflict; • Recognizing the external forces (e.g. ideological, institutional, structural, economic, and interpersonal) that shape our way of “doing” and “being” in conflict; and • Understanding the constructed and cultural meanings, the historical significance, rhetorical purposes, and systemic tensions expressed by conflict activities. Specific learning objectives for this course are to develop an ability to: 1) Articulate your own implicit theoretical positioning toward conflict; 2) Name and describe a number of dominant theorists and theories of conflict; 3) Demonstrate how theory is related to fact-finding, conflict analysis, and intervention strategies. CLASS SCHEDULE/READING DATE I would advise that all readings be done before the start of the course. Failure to do so will put you in a deleterious position in understanding the class course material. Required Texts & References: a) Laurie S. Coltri Alternative Dispute Resolution: A Conflict Diagnosis Approach (2nd Edition) [Paperback] b) Roger Fisher and William Ury, Getting to Yes, Penguin, 1991. c) John Dewey, Democracy and Education, The Free Press 1944 d) Journal articles to be placed on Moodle Course Assignments (APA version 6.0 required). Evaluation: a) In-class participation, including in-class simulations: 10% b) Research Proposal: 30%, First Day of Class: Details of assignment to be sent out 30days before the class starts. c) Oral presentation on research paper: 20% d) *Research paper: 40%, Two weeks from the last day of class TOTAL: 100% Presentations are on the last day of class. Please be prepared. *The research paper is expected to be 20-25 typed, double-spaced pages in length, and will be based on student research about ADR in the workplace. IMPORTANT: For any extensions to be approved, a medical note is required. Three (3) points a day (including weekends), shall be deducted for all unapproved extensions. Course Grade Evaluation: -Minimum grade requirement for graduate program: B -Grade Equivalencies: A+ 96-100 A 90-95 A85-89 B+ 80-84 B 75-79 BC+ C D F 70-74 65-69 60-64 50-59 Under 50% Academic dishonesty will cancel out all the calculations above and result in a final grade of F-AD (Fail-Academic Dishonesty) (refer to the Graduate Calendar, section 5.3.2) Instructor / Course Evaluation: The anonymous course evaluations will be completed online. All students are expected to complete the evaluation. Dates of the evaluation will be communicated by the instructor through the Graduate Studies Office. Proposed Class Schedule: Day 1 Read entire book Getting to Yes Laurie S. Coltri Alternative Dispute Resolution: A Conflict Diagnosis Approach (2nd Edition) [Paperback] Chapter 1. Defining Terms, 1 Definitions, 2 What Is Interpersonal Conflict?, 2 Participants in Conflicts, 5 A Typology of Dispute Resolution, 7 Exercises, Projects, and “Thought Experiments”, 11 Chapter 2. Understanding the Foundations of ADR, 12 Minimizing Perceptual Error and Judgmental Bias, 16 Individual Sources of Perceptual Distortion, 16 Distorted Perception Arising from Escalated Conflict, 19 How Conflict Escalation Leads to Perceptual Error, 20 Cultural Sources of Distorted Perception: The “Invisible Veil”, 23 Perceptual Distortion and Conflict Resolution: Conclusion, 25 Focusing on Interests, Rather Than on Positions, 26 Interests, Values, and Needs, 28 Interests, Values, and Needs of Constituents, Agents, Advocates, and Others, 32 Generalizing the Significance of Interests, Values, and Needs, 32 Tailoring the Process to the Conflict’s Causes, 33 Sources of Conflict, 33 Impediments to Constructive Resolution, 38 Promoting Psychological Ownership, 41 The Benefits of Promoting Cooperation, 43 Efficiency, 44 Resource Optimization, 44 Conflict Containment, 45 Relationship Preservation, 45 Cooperation and ADR, 46 Competition’s Role, 47 Using Power Effectively, 47 BATNA and WATNA as Elements of Expert Power, 50 Understanding the Foundations of ADR: Putting It Together, 51 Exercises, Projects, and “Thought Experiments”, 51 Recommended Readings, 54 Day 2 Chapter 3. Mediation: An Introduction, 57 Basic Definitions, 58 Mediation, 58 The Facilitative-Evaluative Distinction, 59 Facilitative Mediation, 60 Evaluative Mediation, 60 Processes Related to Mediation, 61 Settlement Conference, 62 Facilitation, 63 Conciliation, 63 Collaborative Law, 63 Uses of Mediation Today, 64 Approaches to Mediation, 67 Triage Mediation, 68 Bargaining-Based Mediation, 69 Pure Facilitative Mediation, 72 Transformative Mediation, 74 Narrative Mediation, 76 Participant Roles in Mediation, 77 Mediator(s), 77 Disputants and Their Lawyers, 78 Paralegals (Legal Assistants), 81 Constituents and Dependents, 82 Consultants and Experts, 83 Stages of Mediation, 83 Initial Client Contact, 84 Introductory Stage, 85 Issues Clarification and Communication, 86 Productive Stage, 88 Agreement Consummation, 90 Debriefing and Referral, 90 What Do Mediators Do?, 90 Facilitative Tactics in Mediation, 90 Educating, 91 Structuring the Negotiation, 92 Improving Communication, 92 Handling Emotions, 92 Maintaining Disputant Motivation, 96 Evaluative Tactics in Mediation, 96 Instilling Doubt, 96 Offering Opinions About the Case (Case Evaluation), 98 Caucusing, 99 Exercises, Projects, and “Thought Experiments”, 101 Recommended Readings, 103 Chapter 4. The Law and Ethics of Mediation, 106 Introduction: Why Regulate Mediation?, 107 Preserving the Essence of Mediation, 108 Ensuring the Effectiveness of Mediation, 112 Protecting Other Rights, 113 Legal Issues in Mediation, 114 Confidentiality, 114 Waiver of Confidentiality, 117 Consent of the Participants, 117 Mediator Malpractice or Malfeasance Claim or Defence, 118 Protection of the Mediation Process, 118 Matter to Be Revealed Not Confidential to Begin With, 119 Evidence of a Crime or Child Abuse/Neglect, 120 To Uphold the Administration of Justice, 120 Conflict with Another Explicit Law, 123 Implications of Regulation of Mediator Confidentiality, 123 Mandating Mediation, 125 Coercion in Private Mediation, 127 Coercion in Court-Connected Mediation, 129 Implications of Coercive Elements in Mediation Programs, 135 Provision of Legal Services by Mediators, 135 Behavior of Legal Advocates During Mediation, 136 The Duty to Advise Clients About Mediation and Other ADR Processes, 137 Mediation and the Duty of Vigorous Advocacy, 139 Mediator Behavior, 140 Impartiality and Neutrality of Mediators, 140 Regulation of Mediator Competency, 145 Regulation of Mediator Qualifications, 146 Marketability, 147 Enforceability of Mediated Agreements, 148 Exercises, Projects, and “Thought Experiments”, 150 Recommended Readings, 152 Day 3 Chapter 5. Arbitration, 154 From “People’s Court” to “Creeping Legalism”: The Dilemma of Modern Arbitration, 155 A Brief History of Arbitration in the United States, 156 Arbitration Between a Rock and a Hard Place, 159 Varieties of Arbitration, 159 Executory and Ad-Hoc Arbitration, 160 Administered and Nonadministered Arbitration, 160 Interest and Rights Arbitration, 161 Other Arbitration Varieties, 161 Arbitration’s Place in Fostering “Good Conflict Management”, 162 Process of Arbitration, 164 Creating the Arbitration Contract, 164 Demanding, Choosing, or Opting for Arbitration, 166 Selecting the Arbitrator or Arbitration Panel, 166 Selecting the Procedural Rules, 166 Preparing for Arbitration, 168 Participating in the Arbitration Hearing, 169 Issuing the Arbitration Award, 170 Enforcing the Award, 170 Law of Arbitration, 171 Before Arbitration, 172 When Should a Dispute Be Arbitrated? Enforceability and Arbitrability, 172 Enforceability, 172 Arbitrability, 174 Suspending Court Proceedings and Compelling Arbitration, 177 Special Problems in EEOC Cases, 178 During Arbitration, 179 Arbitrator Misconduct, 179 Privacy and Confidentiality, 179 After Arbitration, 181 Enforcement of Arbitration Awards, 181 Review of Arbitration Awards, 181 Vacatur, 182 Arbitration Agreements That Specify Reviewability, 186 Choice of Law, 186 Choice of Law During Arbitration, 187 Choice of Law in Matters of Enforceability, Arbitrability, and Reviewability, 187 Exercises, Projects, and “Thought Experiments”, 189 Recommended Readings, 192 Chapter 6. Nonbinding Evaluation, Mixed (Hybrid), and Multimodal Dispute Resolution Processes, 193 Nonbinding Evaluation, 194 Nonbinding Arbitration, 196 Minitrial, 196 Summary Jury Trial, 197 Neutral Evaluation, 198 Dispute Review Boards, 199 Day 4 Legal Issues in Nonbinding Evaluation, 200 Mixed and Hybrid ADR, 200 Varieties of Mixed, or Hybrid, Processes, 201 Med-Arb, 201 Arb-Med, 202 Mediation Windowing, 202 Incentive Arbitration, 202 Minitrial, 203 Multimodal ADR Programs and Processes, 203 Ombuds, 203 What Is an Ombuds?, 204 Basic Features of Ombuds: Neutrality and Confidentiality, 205 Critical Features of Competent Ombuds, 206 Dispute Resolution Systems, 208 Court-Connected ADR, 212 History of Court-Connected ADR, 212 Typical Features of Court-Connected ADR, 215 Issues in Court-Connected ADR, 217 Online ADR, 217 Varieties of ODR, 219 Special Considerations in ODR, 222 Advantages and Disadvantages of ODR, 222 Legal Issues in ODR, 227 Chapter 7. Putting It All Together: Selecting Optimal ADR Processes for Clients and Disputes, 233 Advantages and Disadvantages of ADR Processes, 234 Mediation, 234 Advantages of Mediation, 235 Efficiency Considerations, 235 Conflict Management and Prevention, 237 Relationship Preservation, 240 Comprehensiveness, 240 Dealing Effectively with Meta-Disputes, 243 Disputant Quality of Consent, 244 Settlement Durability, 245 Individual Transformation, 247 Minimization of Conflicts of Interest with Legal Counsel, 248 Advantages of Litigation Over Mediation, 249 Guaranteed Outcome, 249 Nature of Enforceability, 249 Legal Precedent, 250 Privacy Issues, 251 Mediation and Low-Power Disputants, 252 Mediation Isn’t the Option of Last Resort, 256 Advantages of Negotiation Over Mediation, 256 Summary: Advantages and Disadvantages of Mediation, 256 Arbitration, 256 Compared with Litigation, 258 Compared with Negotiation, 260 Compared with Mediation, 261 Nonbinding Evaluation, 262 Compared with Litigation, 262 Compared with Arbitration, 265 Compared with Mediation, 266 Summary: Advantages and Disadvantages of Nonbinding Evaluation, 267 Mixed and Hybrid ADR Processes, 268 Med-Arb, 268 Arb-Med, 270 Mediation Windowing, 271 Incentive Arbitration, 271 Minitrial, 272 Ombuds, 272 Dispute Resolution Systems, 273 Online Dispute Resolution, 273 Summary: Advantages and Disadvantages of ADR Processes, 273 Dispute Resolution Process Selection Methods, 273 Day 5 Presentations Instructor suggestions for getting the most out of the course: All readings must be done before the week of classes. This course is taught in an unstructured fashion it requires lots of independent learning. Attendance at Lectures and Practical Work: (refer to the Graduate Calendar, section 5.3.1) 1. All students are expected to be regular in their attendance at lectures and labs. While attendance per se will not be considered in assessing the final grade, it should be noted that in some courses participation in class activities may be required. 2. For limited enrolment courses, students who are registered but do not attend the first three classes or notify the instructor that they intend to attend, may have their registration cancelled in favour of someone else wishing to register for the course. 3. Students who are unable to attend a scheduled instruction period because of illness, disability, or domestic affliction should inform the instructor concerned as soon as possible. 4. Instructors may excuse absences for good and sufficient reasons.