A Report on Research into the Integration of Safety

A REPORT ON RESEARCH INTO THE INTEGRATION OF SAFETY

PLANNING AND THE COMMUNICATION OF RISK INFORMATION

WITHIN EXISTING CONSTRUCTION PROJECT STRUCTURES

Cameron, Iain

Duff, Roy

Department of Building & Surveying, Glasgow Caledonian University, U.K.

Department of Building and Civil Engineering,University of Manchester

Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST), U.K.

Introduction – Health & Safety Management in Construction

The performance standards traditionally associated with the delivery of construction projects are time, cost and quality. However, in recent think-tanks such as The Construction Task Force

(www.construction.detr.gov.uk/cis/rethink/index.htm), The Construction Best Practice Programme

(www.cbpp.org.uk), The Key Performance Indicators Zone (www.kpizone.com), and The Movement for Innovation (www.m4i.org.uk) have set additional targets, challenging construction to plan more thoroughly and improve performance in many areas, including a greatly increased attention to health and safety.

Today’s thinking seriously challenges the old model of time/cost/quality trade-off, which suggested that an improvement in one must lead to deterioration in at least one of the others. It now extends the total quality management philosophy that ‘quality is free’ and embraces the premise that delivery in one area, safety, can actually lead to benefits in other areas, time and cost. The importance of effective construction planning and control in the communication and avoidance of health and safety risks cannot be overstated but the fundamental premise which underlies this research, is that this need not and should not be a separate exercise aimed solely at health and safety. Effective management will embrace all production objectives, as an integrated process, and deliver construction, which satisfies all these objectives, not one at the expense of the others.

Health and Safety Targets

The UK Government has recently set ambitious targets to reduce workplace accidents and ill health across all industries in

“Re-vitalising Health and Safety”.

However, construction’s safety performance is worse than most industries, currently deteriorating and a major component of society’s accident and ill health experience. Because of this the Health & Safety Commission and the Deputy

Prime Minister hosted a Construction Summit entitled “Turning Concern into Action” on 27 February

2001. The summit communicated key ‘Action Plans’ to improve performance and meet new ambitious targets, set by CONIAC (Construction Industry Advisory Committee in the UK), for the construction industry. The Deputy Prime Minister has made it clear that he wants decisive action. This proposed research will, inter alia, develop key performance indicators which will assist HSE and industry to

“Work Well Together” to realise some of these improvements. The targets currently being pursued can be summarised below.

“Re-vitalising Health and Safety” targets to be reached by the year 2010 for all industries include:

1- To reduce work days lost (per 100 000) by 30% due to accidents

2- To reduce the incidence rate of fatal and major injury accidents by 10%

3- To reduce cases of ill health by 20%

“Turning Concern into Action” targets to be achieved by 2005 and 2010 by construction industries are:

1-To reduce the incidence rate of fatalities and major injuries by 40% (2005) and 66% (2010)

2-To reduce the incidence rate of cases of work-related ill-health by 20% (2005) and 50% (2010)

3-To reduce the number of working days lost per 100,000 workers from work-related injury and illhealth by 20% (2005) and by 50% by (2010).

1

Communication and Information Flow

Effective health and safety planning to improve risk information, communication and control are fundamental parts of the UK’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE) current construction focus –

“Working Well Together” (wwt.uk.com). The flow of appropriate risk management information is also fundamental to much of UK health and safety legislation:

The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999

The Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 1994

The Construction (Health, Safety, Welfare) Regulations 1996

The Health and Safety (Consultation with Employees) Regulations 1996

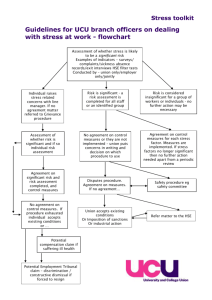

However, the Construction (Design and Management) ACoP Consultative Document acknowledges that CDM compliance documents, written specifically for the purpose, are sometimes cumbersome and add little value to management processes generally. Because of this, the ACoP document indicates that stakeholders should treat CDM information provisions as part of the construction planning process. The ethos is: "minimise bureaucracy and maximise performance".

To comply with all this legislation, and to establish effective health and safety planning and control, a large number of management procedures are required. The authors believe that health & safety is best managed within a contracting organisation’s existing production management structure and procedures, as any attempt to overlay a safety specific structure is likely to meet resistance and organisational constraints.

Industrial Problem to be Investigated by the Research

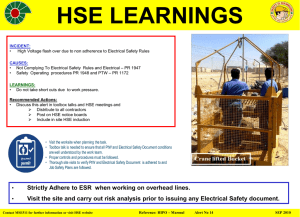

Effective planning for health and safety is essential if projects are to be delivered on time, without cost overrun, and without accidents or damaging the health of site personnel. These are not easy objectives as construction sites are busy places where time pressures are always present and the work environment constantly changing.

The construction industry tends to be under resourced and under planned in relation to other industries and this promotes a crisis management approach to all kinds of production risk, a feature of construction culture which can impact on health and safety management. However, the industry frequently demonstrates that it can plan proactively, to manage production risk, if it is required to do so. Consider highly planned works, such as those requiring a temporary rail possession, which almost invariably run smoothly. This type of work is managed in a highly focused way and planned in great detail. This contrasts with routine work where recent collaborative EPSRC(IMI) research by Dundee

University and UMIST (Dr Duff) has demonstrated that productivity increases of at least 20% are readily available from a combination of more rigorous short-term planning, clear communication of goals, performance measurement and a participative approach to obtaining commitment at all levels.

This approach is clearly cost-effective. There is no reason why health and safety performance should not benefit from the same approach and achieve at least as much improvement. Indeed, research for

HSE (Duff et al., 1993), adopting only the performance measurement and goal-setting principles, has shown that well over 20% reduction in unsafe operative behaviour is achievable (HSE Contract

Research Report, CRR 229/1999); and more recent work has demonstrated comparable improvements in site management behaviour related to its health and safety responsibilities (Cameron, 1999).

The problem investigated by the programme of research outlined in this paper is how best to promote the effective integration of health and safety management into project planning and control in all construction activity – complex and routine – and thus achieve similar improvements. This will involve the development of methods that will ensure that health & safety management truly permeates construction sites by 'building-in' safety planning and control as a core aspect of normal time and resource management, rather than attempting to run separate safety procedures as 'bolt-on' extras.

In order to achieve a holistic approach to the management of construction, it is important to view health and safety planning as an integral aspect of production planning from the beginning . This

2

should involve, for example, including safety risk assessment as part of the general management of construction risk; and including specific safety activities and milestones on the master construction programme. This allows safety activity to be monitored in the same way as production and embraces the ‘what gets measured, gets done’ philosophy of management. For example, the authors’ chose a

‘Linear Responsibility Chart’, detailing who does what, when and where (CIOB, 1991). This monitors health and safety responsibilities, along with other responsibilities, to avoid safety management being overlooked as a result of unclear priorities. Safety arrangements and effort then becomes controlled and visible as a central objective of production management.

This thinking demonstrates that strategic planning for Health and Safety begins at the very start of the project and a commitment to proactive safety planning can be evidenced by a review of the allocation of responsibilities for safety (Health and Safety Plan). This should be clear from a review of the project organisational structure chart which ought to detail who has responsibility for what (safety roles).

The following is an example of the extent of a comprehensive set of safety roles which form the foundation of the more advanced ‘Linear Safety Responsibility Chart’:

Site Manager

- Holds subcontractor pre start meetings

- Updates risk assessment control chart for all work activities

- Delivers safety induction talks

- Chairs safety committee

- Maintains records of statutory records

- Conducts safety audits with safety manager

Sub agent

Fire Inspection and fire marshal and first aid

Conducts Tool Box Talks

Conducts works risk assessments

Inspects and audits subcontractors and site for safety

Deputy for safety induction talks

Crane and lifting operations ‘appointed person’

Conducts works risk assessments

Inspects and audits subcontractors and site for safety

Project Engineer

Conducts excavation inspections

Conducts RA for temporary works

- Temporary works co-ordinator who oversees safe installation and removal

General Foreman

Conducts scaffold inspections

Communicates visible commitment to safety

Crane co-ordinator

Works Foreman

Inputs in to risk assessment

Procures safety plant and PPE and inspects same

Deputises for Site Manager and Sub Agent for safety acts

Builds safety consideration in to daily part of work instructions

Chargehands

- Inputs in to risk assessment

Procures safety plant and PPE

Inspects work equipment and PPE

Identifies extra safety training needs of his squad

Tradesmen and Labourers

Report unsafe acts and conditions

Maintain their own PPE

Co-operate with the main contractor

3

Research Objectives

1.

To produce a theoretical model of construction management, planning and control, and practices for the integrated management of health and safety risks.

2.

To improve the effectiveness and practicality of this model through consultation with experienced practitioners.

3.

To investigate current construction planning, control, and supervisory methods and tools, and evaluate contractors’ methods for the management of health & safety risk.

4.

To identify gaps between current health and safety management practice and the model, and revise the model to benefit from any improvements suggested by this investigation.

5.

To field test the revised model in order to further improve the validity of the safety planning model by taking account of these practical experiences.

6.

To produce a guide to best planning and control practice in integrated construction management of health and safety risk, including a set of ‘Key Integrated Safety Management Planning

Procedures’ and 'Key Safety Performance Indicators'.

Research Method Employed

Objective 1: The first objective will be achieved by investigating available literature on good practice in construction management, in general, and legislation and other literature on health and safety management, in particular. This will cover site investigation, site set-up and mobilisation, site layout planning, contractor design (including temporary works), method statements, risk assessment, programming and allocation of resources, short-term planning and control, construction site supervision, the management of design variations throughout construction, and commissioning and client handover. A draft, theoretical model of ‘best-practice’ procedures, information flows and planning tools will be produced, showing source, destination, content, timing and frequency of communications and the roles and responsibilities of typical participants in the construction management process. This will show the integration of health and safety management with the general planning and site management processes.

Objective 2: The draft model will be tested for completeness, perceived value, practicality and the potential for integration into real construction sites, by consultation with a range of experienced practitioners; and modified accordingly. This interaction will use a selection of interview, Delphi and focus group techniques, as appropriate and depending on opportunity and availability of participants.

Objective 3: The next objective is to investigate how far actual practice diverges from the modified model. This will involve the collection and mapping of data on a variety of live case-study construction sites by: interviews with key project actors; passive observation of site induction meetings, planning meetings, tool-box talks etc.; and, review of site management documentation, such as site investigations, risk assessments, construction programmes, method statements etc. A gap analysis of health and safety content and quality will then be carried out, against criteria derived from the model. Instances of deviation from the model, particularly instances of failure to comply with accepted good practice or legal requirements, or instances of dealing with health and safety as a peripheral issue, will be recorded and reasons sought. Instances of alternative or better ways of achieving the model objectives will be recorded for inclusion in the model.

Objective 4: This will involve developing strategies for the introduction of any previously untried health and safety management procedures in the model (effective ‘best-practice’ procedures discovered during observation of current practice may not require any further field testing). This will be done with the assistance of industrial collaborators, and recording practitioner feedback. Strategies will focus particularly on ways of integrating health and safety management, such as health and safety plans and risk assessments, into equivalent mainstream construction management procedures. The drivers for change will include improved overall communication flows, methods of reducing the duplication of safety effort and ways of promoting teamwork and consultation etc., to the benefit of the whole construction management process. The model mechanisms are clearly not yet determined but current thinking suggests that they will include: structured meeting agendas; safety management performance indicators; goal setting and 360o feedback; risk assessment workshops; integration of accident/ dangerous occurrence reporting with other feedback into short-term planning procedures;

4

collection and feedback of employee contributions into the whole short-term planning process, including health and safety; assessment of employee experience and competence across all factors of performance, including health and safety; re-engineering site management supervisory practices, such as induction and tool-box training, to integrate risk awareness with production related information.

Objective 5: This will involve the production of a set of documented Key Integrated Safety

Management Procedures which can be used by HSE and industry to support a strategy for integrating health & safety management within existing construction management systems. These aids will also be used as the basis for a set of Key Performance Indicators which can help monitor health & safety activity within construction planning and control.

Conclusion

This paper has presented a planned programme of study which is currently being negotiated with the

UK’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE). The initial findings of the study and early collaborator consultation has suggested that health and safety is not seen as an integral aspect of work planning.

Instead, risk information and avoidance strategies are conducted at a later date and risk assessments and control plans are viewed as separate activities - sometimes ‘the domain of the specialist’. For example, construction barcharts seldom make reference to key safety items (e.g. completion of risk assessment, approval of method statements, training events etc). This suggests that safety planning is being conducted too late in the process in order to truly permeate site planning and supervisory practices. This paper recommends that more research is required to find effective and efficient ways of

(easily) embedding safety planning and risk communication within the day-to-day planning tasks of the construction site management team.

References

Cameron I.

, 1999, A Goal Setting Approach to the Practice of Safety Management in the Construction

Industry: Three Case Studies.

PhD Thesis. University of Manchester Institute of Science and

Technology (UMIST). Department of Building Engineering.

Cameron, I. & Duff, A.R.,1999, “Constructing a construction safety culture: a human approach”

Construction Paper 105, Construction Information Quarterly, Vol 1, Issue 2 The Chartered

Institute of Building. P.22-27.

CIOB, 1991, Planning and programming in construction – a guide to good practice.

Chartered

Institute of Building Publications, Englemere, Ascot.

CIRIA, 1997, Experiences of CDM: Report No. 171.

Construction Industry Research and Information

Association. London SW1.

Duff, A.R., Robertson, I.T., Cooper, M.D. & Phillips, R.A. (1993) “ Improving safety on construction sites by changing personnel behaviour ” Contract Research Report 51/1993, Health & Safety

Executive, ISBN 011 882 1482.

Egan, J., 1998, Re thinking construction.

The report of the Construction Task Force on the scope for improving the quality of UK Construction, DETR London.

HSE, 1997, Evaluation of the CDM Regulations 94 . The Consultancy Company. HSE Contract

Research Report 158. HSE Books.

HSC, 2000, Re-vitalising Health & Safety: strategy statement . June 2000, HSE/DETR.

HSC, 2000, Proposals for revising the Approved Code of Practice on ‘Managing construction for

Health and Safety’ . CDM Consultative Document. Aug 2000, HSE.

5

HSC, 2000, Securing Health Together . MISC225. August 2000, HSC/DETR.

HSE, 2000, Health and Safety Benchmarking: improving together . HSE Books.

HSE, 2000, Re-vitalising Health and Safety in the Construction Industry: developing an agenda for action.

Working Well Together Conference. London, June 2000.

HSE, 2000, Tackling Health Risks in Construction: developing an agenda for action.

Working Well

Together Conference. London, October 2000.

Robertson, I.T., Duff, A.R., Marsh, T.W., Phillips, R.A. Weyman, A.K. & Cooper, M.D. (1999)

“

Improving safety on construction sites by changing personnel behaviour – Phase Two

”

Contract

Research Report 229/1999, Health & Safety Executive, ISBN 0 7176 2467 6.

Internet References

HSE’s ‘Working Well Together’ campaign. wwt.uk.com.

Egan’s Report.

www.construction.detr.gov.uk/cis/rethink/index.htm.

Key Performance Indicators Zone. www.kpizone.com.

Movement for Innovation (M4I). www.m4i.org.uk.

Construction Best Practice Group (KPI’s). www.cgpp.org.uk.

6