Paolo Jasa's Essay "Of Robots and River Spirits: Environmentalism

advertisement

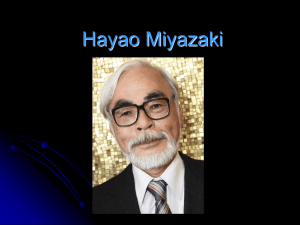

Of Robots and River Spirits: Environmentalism in Western and Eastern Animation Paolo Jasa ENGL 367: Adv. Expository Writing Professor Peterson 28 March 2012 Jasa 2 Of Robots and River Spirits: Environmentalism in Western and Eastern Animation The movie opens with several shots of deep space as the song “Put On Your Sunday Clothes” from the stage musical Hello, Dolly! The camera then pans over a computer-generated version of Earth. At this angle, it’s obvious that it’s the very same world we know and love…but it’s tinged in a sickly green. Suddenly, the camera zooms in rapidly, past an atmosphere littered with decaying, abandoned satellites and other space debris and through clouds tinged with the similar green from earlier. The camera slows, flying through what looks like an eerie mountainous landscape. Mountains not made of rock, but of garbage. Garbage piled higher than the desolate buildings around it, outnumbering and dwarfing the skyscrapers that stand alongside them. It is here that the audience is introduced to the almost silent, eponymous protagonist of the film, whose sole purpose is to continually process garbage into small cubes and stack them into the ever-growing monoliths of waste seen in the beginning of the film. The protagonist is a Waste Allocation Load Lifter - Earth class, colloquially known in the movie’s universe as WALL-E. To some, the subtle yet undeniable environmental message against consumerism and excess in the movie feels a little forced. However, the message is nothing new to the medium; countless other films, animated or otherwise, have handled similar environmental themes with varying degrees of success. Take for example, the opening of the film Kaze no Tani no Naushika, or, as localized in the West, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: after the opening credits that show her world’s violent history, the young, female protagonist Princess Nausicaä touches down on the sands next to the Toxic Jungle to collect specimens of various flora and fauna. She happens upon a spent carapace of one of the largest creatures to roam the jungle, a race of gigantic armoured caterpillar-like creatures known as the Ohmu. It’s quickly introduced Jasa 3 that the Ohmu’s tough shells are used as raw material by the people living in this postapocalyptic wasteland as Nausicaä harvests one of the shell’s clear eyes for later use. However, poisonous spores soon fill the sky, rendering her unable to leave the forest until they clear, stopping her progress. As soon as the noxious hail ends, she hears the cry of an enraged Ohmu and quickly finds a traveller being chased down by one of the enormous bugs. By using a wind whistle and speaking to the giant creature, Nausiaä calms the beast and sends it away. The environmental message of living in harmony with nature here is subtle, but isn’t readily apparent until much later in the film and until more of the world’s history and the world’s current state is explained. Having said that, it is also radically different from WALL-E’s message. The two animated films carry similar thematic messages, use similar thematic elements and cater to a similar audience, yet the exact message they carry are different. In fact, the environmental messages that the films made by Disney are markedly different from those made by Studio Ghibli; it seems that there are distinct ideological mores at play here that are exemplified by either company, but may extend to several others in the medium. I believe that the inherent difference in the portrayal of environmental messages is based on the cultural biases of either company’s home countries, as seen in the animated works of Disney, and its subsidiary Pixar, versus Studio Ghibli, specifically those of its star auteur Hayao Miyazaki. American media conglomerate Disney is no stranger to any of the messages of environmentalism; in fact, they were some of the first studios to popularize the nature film and have a long history of making them, no small thanks to their founder. Margaret J. King acknowledges Disney’s influence over the company’s view on environmentalism in her paper on the company’s True-Life Adventure series: “Walt Disney did not invent popular interest in nature. But he was the first to film nature drama for commercial release according to a set of Jasa 4 formulas that capture and cultivate later-twentieth- century attitudes….Disney productions' empathetic identification with animals laid the groundwork for the American eco-political climate from the 1960s onward” (2). Around the same time period, Disney created one of their most celebrated and, according to “child psychologists of the era,” most traumatic animated features that changed an entire generation’s view on nature, Bambi, beginning a trend towards the “odd identification with animals and against Man the Hunter” (King 4). Fast forward through Disney’s animated film canon and it’s easy to see that Bambi’s thematic influence has continued in such works like The Jungle Book in 1967, The Rescuers in 1977, and The Rescuers Down Under in 1990, where humans usually take a back seat to the talking animals. Pixar Animation Studios continued this trend in their line of incredibly successful feature films through WALL-E in 2008, which deals with similar environmental themes in unique way: by placing it in the background. The story of WALL-E revolves around an Earth that has long since been abandoned by its inhabitants, who have grow in extreme lethargy and size while in space, to allow robots like WALL-E to retake the world from the piles of garbage that humans have produced. WALL-E is the last of his kind left on Earth and enjoys his solitary life, until EVE, or Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator, arrives on Earth, with the intent of finding vegetation, a sign that the Earth is ready to be inhabited again. Smitten with the new arrival, WALL-E tries his best to ‘woo’ her, and the two eventually become friends. However, when WALL-E shows EVE signs of vegetation, EVE is taken back to the main spaceship, with WALL-E close behind. Soon, a plot is uncovered to keep the humans in space, and EVE, WALL-E and an entire cast of other robots and humans eventually find themselves back on Earth to get WALL-E fixed after trying to rescue EVE and to get humans back on Earth again. According to Jennifer A. English’s paper Jasa 5 WALL-E’s Rhetoric: An Ecological Sermon from a Strange Preacher, the way the movie portrays the relationship between the two protagonists against the backdrop of a world that’s already become an ecological dystopia is nothing short of the nuanced storytelling that boosted the popularity of Pixar’s films. WALL-E handles the responsibility of its “unavoidable” message well, “and gently confronts the movie going audience with the environmental challenges faced today” without being overly heavy-handed or preachy (English 3). In fact, the ecological and environmental rhetoric within the film itself is not the direct focus of the story: “WALL-E did not explicitly purport an environmental message using facts or statistics, but tried to subtly enter it into its audience’s mind while focusing on the robots’ love story” (10). In essence, English believes that “WALL-E tries to persuade its audience of the importance of taking care of our environment…the film’s vivid simplicity works to promote a return to valuing Mother Earth” (23). She even quotes director Andrew Stanton’s apprehension towards the film’s use of said messages: Stanton defends himself by saying “the environment talk started to freak me out. I don’t have much of a political bent, and the last thing I want to do is preach” (qtd. in English 23). However, English has no doubts of the film’s status as an ecological “jeremiad,” or “work that accounts for the misfortunes of an era as a just penalty for great social and moral evils, but holds out hope for changes that will bring a happier future” (English 3, “Forms of Puritan Rhetoric: The Jeremiad and the Conversion Narrative”). In her work, she delves into how WALL-E, in light of similarly environmentally-oriented films of the early 2000’s, like Al Gore’s acclaimed documentary An Inconvenient Truth and The Day After Tomorrow, seemed to have taken the message down a very specific path that may, ironically, hinder the progress of “the mainstream green movement” all these films are trying to speak through (3). Jasa 6 The problem with WALL-E, according to English, can be summed up in a single word: anthropocentrism. English quotes Katherine Kortenkamp from the author’s work on the subject: “anthropocentrism considers humans to be the most important life form, and other forms of life to be important only to the extent that they affect humans or can be useful to humans” (qtd. in English 18). English takes it to the next logical step by realizing the “anthropocentric worldview causes humans to protect nature so far as it protects themselves, which can often lead to shortterm actions based upon immediate human needs, but does not lead to a change in valuing nature for itself” (19). In short, nature is only as valuable as its utilitarian value to human beings. WALL-E is guilty of this when one of its major plot points involve going back to Earth in order to repopulate it with the progeny of its original inhabitants who abandoned it! However, there’s an even deeper problem within the movie itself that rings through other movies of this type as well. English argues the movie “projects human characteristics onto its non-human characters in order to help the audience relate to the story, leading the audience to value non-human characters since they are human-like,” thus allowing humans to become emotionally involved with the characters, even though what is perceived as speech and emotion is literally just the inhuman clicks and whirrs of machinery (19). This characterization was one of the reasons why Walt Disney’s True-Life Adventure series became so popular, and why so many of Disney’s animated features involve anthropomorphized animals that sing and dance; when humans see animals acting human, they immediately regard them with an more empathic response. Coupled with the idea of anthropocentrism, and people are likely to create “the perception of nature as a neutral or hapless system that cannot care for itself, needing human stewardship to survive,” an implication that would create more harm that good as humanity begins to think of itself as the savior of nature, constantly requiring human intercession in order to function (King 12). Jasa 7 And this is a problem throughout the Disney animated canon, whether or not the work has environmental themes within it, and throughout several other similarly themed works. One such work that is especially guilty of such behavior is Ted Turner’s Captain Planet and the Planeteers. Donna Lee King examines the inherent anthropocentrism within the work, and finds that the concept has taken another step towards a direction that negates any good that it creates as a work promoting environmentalism: the show’s close ties to commercialism. King realizes that there’s a “paradox in environmentalizing kids” through a television show that aims to sell its merchandise to its viewers, as “at the same time that they are admonished to conserve, recycle, reuse and respect the limits of the earth, children are aggressively canvassed and cajoled to buy products and consume goods” (108). To turn it back to the case-study of WALL-E, English recognizes that “while WALL-E’s message may encourage protecting the environment — even if only to save humans — its very creation serves to produce more waste in the forms of toys and videogames sold by Disney” (23). The self-centered ideals that stem from the culture of the West, or at least the United States, choke and constrain the very ideas that it tries to preach, rendering their messages ineffective, no matter how nuanced its story. Pixar’s success in such storytelling, however, did not spring from a vacuum. Within the halls of that animation studio are some of the biggest fans of an equally successful animation studio, located on the other side of the world. Appropriately enough, the majority of this studio’s animated works is about a world away from their counterparts in Disney, and is just about as famous on their turf as Disney is on theirs. I speak, of course, about Studio Ghibli. Long considered to be one of the most creative and successful animation studios in Japan, Studio Ghibli is famous for all of its films, one of which remains to be the only animated feature outside Jasa 8 the United States to win the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, many of which were directed by Studio Ghibli founder and legendary animated film auteur Hayao Miyazaki. Like Pixar, Miyazaki is famous for his work in the medium, and more so the messages that he brings to all of his works. In The ecological and consumption themes of the films of Hayao Miyazaki, the authors Kozo Mayumi, Barry D. Solomon, and Jason Chang are “struck by the clarity of his message on ecological and societal problems, even when those problems are rather complex (which is often the case)” (2). A viewing of one, or all of his films brings true a message that he’s tried to convey in his work on environmental issues; Miyazaki says that: We need courtesy toward water, mountains, and air in addition to living things. We should not ask courtesy from these things, but we ourselves should give courtesy toward them instead. I do believe the existence of the period when the ‘power’ of forests was much stronger than our power. There is something missing within our attitude toward nature. (qtd. in Mayumi, Solomon & Chang 3) Much unlike the Western ideals of human intercession and intervention, Miyazaki instead supports the idea of ecological pacifism and stewardship. According to Roslyn McDonald’s work Studio Ghibli Feature Films and Japanese Artistic Tradition, such a concept is inspired by his cultural and artistic surroundings in Japan, such as “the animism, anthropomorphism and metamorphosis inherent in Shinto” and the “concept of the one-ness of all things” from Buddhism, amongst other influences from Eastern religions and practices (2). This inherently Japanese mix of acknowledging the universal unity of all things and the spiritual essences in all of the aforementioned things is a cultural more that is reflected in almost all of Miyazaki’s works, from Porco Rosso to Ponyo. Like many auteurs, a specific theme on the topic of environmentalism runs throughout Miyazaki’s body of work, a theme that drives him to make Jasa 9 more of such movies to further champion his cause. However, a case study can bring a better understanding of the thematic elements Miyazaki’s films, especially when viewed through the lens of the environmentalist. While there’s a gamut of films to pick from the man’s sizable filmography, I believe the best feature to study would be Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, as its opening has already been compared with WALL-E’s in the beginning of this paper. Appropriately enough, Nausicaä shares several common traits with WALL-E: both Nausicaä’s and WALL-E’s worlds have been ravaged by pollution, both have the key to the survival of humanity through ecological solutions, and both are protagonists radically different from the norm (one is a young, female princess, and the other is a robot). Except, in the Ghibli film, this world is set “a thousand years after ‘The Seven Days of Fire’-the holocaust that rapacious industrialization spawned - the earth is a wasteland of sterile deserts and toxic jungles that threaten the survival of the few remaining human beings” (DeWeese-Boyd 1). The entire gist of the movie revolves around the Princess of the Valley of the Wind, the eponymous Nausicaä, and how she’s essentially a ecological Christ figure, even to the point of dying and rising again, according to Ian DeWeese-Boyd’s paper Shojo Savior: Princess Nausicaä, Ecological Pacifism, and The Green Gospel: “As Nausicaä struggles to lead her world into a sustainable future, she functions as a savior in this post-apocalyptic dystopia, forging a nonviolent path of love aimed at the restoration of harmony between warring human beings and the natural world” (1-2). Next to WALL-E, Nausicaä’s world suffers from a more explicit version of human excess, as rapid industrialization has basically forced the planet’s citizen to compete for the world’s resources in an ever-increasing war. DeWeese-Boyd notes that the beginning of the film basically outline the ecological disaster that was brought on by humanity: Jasa 10 The tapestry shows the violent destruction of the world in haunting images of giant bioengineered humanoid weapons marching over the glowing ruins of the great cities this civilization had built. The attitudes that fueled the violation of the earth, we are led to believe, also fueled the construction and use of these exquisitely powerful weapons-the objectification of nature and human enemies go hand and hand…we see that the exploitive practices of industrialization created the toxic jungle and the giant insects that now imperil humanity. Nature itself has shown the limits of human hubris and avarice both. (7) The complexity of the situation that faces Nausicaä is also indicative of how Miyazaki understands the similar complexity of solving such ecological problems: there are no bad guys to blame for the state the world is in, nor does it do any good to wantonly meddle with the affairs of nature, as it was that self-same meddling that caused the problem in the first place. The message is relatively clear, and is completely in line with the environmentalist thinking that Miyazki believes and champions. From this point forward, it is clear that there are distinct differences between the way the West and the East deals with nature, a distinction that Viktor Eikman makes known in his paper Meadow and Apocalypse: Constructions of Nature in the Early Works of Miyazaki Hayao. He states that, unlike the Western ideal of indiscriminate meddling, one of the main lessons that Miyazaki tries to teach in his films, ecologically speaking, is that “a fundamental philosophical reorientation is necessary for any real change to occur” (Eikman 48). It’s a symbiosis with nature that is required of humans to survive in Nausicaä’s world, as Eikman points out that by “cutting out the eye of an Ohmu and being resurrected on wheat, Nausicaä symbolically communicates a sense that major human impositions can be legitimate, and perhaps sacred” (48). Alongside other Jasa 11 Miyazaki films like Princess Mononoke, Nausicaä’s ideological successor, Pom Poko, and Spirited Away, the idea of humanity keeping their distance from the natural, or at least existing in harmony alongside it, is not only relevant, but central to the films’ main environmental message: balance and harmony. However, cultures do tend to bleed into one another, and a final irony in the popularity of Miyazaki’s work is not lost on Eikman: “even Miyazaki's work, much of it distributed by Disney, is fed into environmentally destructive consumerism” (24). From both the East and the West, the message of protecting the environment rings clear, but the ways and methods by which each studio does so is different. Cultural, social and political biases, as seen in the way Pixar, by way of Disney, and Miyazaki, by way of Studio Ghibli, dictate the lessons imparted by either studio’s films. Like WALL-E, the West believes that only by giving a helping hand can one save the environment. However, like Nausicaä, sociocultural norms in the East believe that a sense of harmony and balance with nature must be achieved and maintained in order to preserve it. If the world were to follow the teachings of either or both of these films, mankind would have no need for a robot to dig through the magnificent piles of garbage we’ve accumulated, nor would we have to rely on a princess to communicate with the mutated beasts that have grown even wilder in the aftermath of a manmade apocalypse. Jasa 12 Works Citied DeWeese-Boyd, Ian. “Shojo Savior: Princess Nausicaä, Ecological Pacifism, And The Green Gospel.” Journal Of Religion & Popular Culture 21.2 (2009): 6. Humanities International Complete. Web. 23 Mar. 2012. Eikman, Viktor. “Meadow and Apocalypse: Constructions of Nature in the Early Works of Miyazaki Hayao.” Nausicaa.net, June 2007. Web. 23 March 2012. English, Jennifer A. “WALL-E’s Rhetoric: An Ecological Sermon from a Strange Preacher.” Digital Commons @ CalPoly, 2010. Web. 23 March 2012. King, Margaret J. “The Audience In The Wilderness.” Journal Of Popular Film & Television 24.2 (1996): 60. Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web. 23 Mar. 2012. Mayumi, Kozo, Barry D. Solomon, Jason Chang. “The ecological and consumption themes of the films of Hayao Miyazaki.” Science Direct, 2005. Web. 23 March 2012. McDonald, Roslyn. “Studio Ghibli Feature Films and Japanese Artistic Tradition.” Nausicaa.net, June 2004. Web. 28 March 2012. Dir. Hayao Miyazaki. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Perf. Sumi Shimamoto (voice), Mahito Tsujimura (voice) and Hisako Kyôda (voice). Studio Ghibli, 1984. Film. Dir. Andrew Stanton. WALL-E. Perf. Ben Burtt (voice), Elissa Knight (voice), Jeff Garlin (voice), Fred Willard, John Ratzenberger (voice) and Sigourney Weaver (voice). Pixar Animation Studios, 2008. Film.