cooper tire - New Jersey Courts

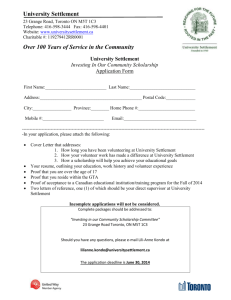

advertisement