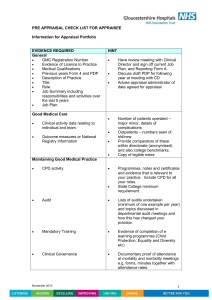

Building Records Appraisal Systems

advertisement