Lecture One - Yerevan State Linguistic University after V. Brusov

advertisement

Lecture One

THE WORLD'S LANGUAGE

MORE THAN 300 M I L L I O N P E O P L E in the world speak English and the rest, it

sometimes seems that English belongs to the world: 'Nobody owns English now'. The statements

identifies the reality of what has happened as English has spread around the globe and become the

world's first choice of lingua franca. Whereas once upon a time it would have been possible to say

that England 'owned' English, and later that the US 'owned' English, insofar as the notion of

ownership relates to matters of historical power and numbers of speakers, the present-day reality is

that the centre of gravity of the language has shifted from these localities. As you know, there is a

sentence in sociolinguistics which tries to relate languages and nationalities: 'If I speak X, then I

am Y'. if I speak Welsh, then I am Welsh', is probably true for virtually all Welsh speakers, if I

speak Finnish, then I am Finnish' must also be very largely true, if I speak Russian, then I am

Russian' is much less true, but still predominantly so. But if I speak English, then I am,.,' well, it

proves impossible to give the sentence a sensible conclusion. You could be from anywhere.

People have been predicting the emergence of English as a global language for at least two

centuries but in a genuine sense of 'global' the phenomenon is in fact relatively recent. A language

achieves a truly global status when it develops a special role that is recognized in every country

For better or worse, English has become the most global of languages, the lingua franca of

business, science, education, politics, and pop music. For the airlines of 157 nations (out of 168 in the

world), it is the agreed international language of discourse. In India, there are more than 3,000

newspapers in English. The six member nations of the European Free Trade Association conduct all

their business in English, even though not one of them is an English-speaking country. When

companies from four European countries—France, Italy, Germany, and Switzerland—formed a joint

truck-making venture called Iveco in 1977, they chose English as their working language because, as

one of the founders wryly observed, "It puts us all at an equal disadvantage." For the same reasons,

when the Swiss company Brown Boveri and the Swedish company ASEA merged in 1988, they

decided to make the official company language English, and when Volkswagen set up a factory in

Shanghai it found that there were too few Germans who spoke Chinese and too few Chinese who

spoke German, so now Volkswagen's German engineers and Chinese managers communicate in a

language that is alien to both of them, English.

For non-English speakers everywhere, English has becdme the common tongue. Even in

France, the most determinedly non-English-speaking nation in the world, the war against English encroachment has largely been lost. In early 1989, the Pasteur Institute announced that henceforth it

would publish its famed international medical review only in English because too few people were

reading it in French.

English is, in short, one of the world's great growth industries. "English is just as much big

business as the export of manufactured goods," Professor Randolph Quirk of Oxford University has

written. " Indeed, such is the demand to learn the language that there are now more students of English

in China than there are people in the United States.

To be fair, English is full of booby traps for the unwary foreigner. Imagine being a foreigner

and having to learn that in English one tells a lie but the truth, that a person who says "I could care

less" means the same thing as someone who says "I couldn't care less," that a sign in a store saying

ALL ITEMS NOT ON SALE doesn't mean literally what it says (that every item is not on sale) but rather

that only some of the items are on sale, that when a person says to you, "How do you do?" he will be

taken aback if you reply, with impeccable logic, "How do I do what?"

The complexities of the English language are such that even native speakers cannot always

communicate effectively, as almost every American learns on his first day in Britain. Indeed, Robert

Burchfield, editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, created a stir in linguistic circles on both sides of

the Atlantic when he announced his belief that American English and English English are drifting

apart so rapidly that within 200 years the two nations won't be able to understand each other at all.

However, it is often said that what most immediately sets English apart from other languages is

the richness of its vocabulary. Webster's Third New International Dictionary lists 450,000 words, and

the revised Oxford English Dictionary has 615,000, but that is only part of the total. Technical and

scientific terms would add millions more. Altogether, about 200,000 English words are in common

use, more than in German (184,000) and far more than in French (a mere 100,000). The richness of

the English vocabulary, and the wealth of available synonyms, means that English speakers can often

draw shades of distinction unavailable to non-English speakers. The French, for instance, cannot

distinguish between house and home, between mind and brain, between man and gentleman, between

"I wrote" and "I have written." The Spanish cannot differentiate a chairman from a president, etc.

English, as Charlton Laird has noted, is the only language that has, or needs, books of

synonyms like Roget's Thesaurus. "Most speakers of other languages are not aware that such books

exist."

On the other hand, other languages have facilities English lacks. Both French and German can

distinguish between knowledge that results from recognition (respectively connaitre and kennen) and

knowledge that results from understanding (savoir and wissen). Portuguese has words that

differentiate between an interior angle and an exterior one. All the Romance languages can

distinguish between something that leaks into and something that leaks out of.

Of course, every language has areas in which it needs, for practical purposes, to be more

expressive than others. The Eskimos, as is well known, have fifty words for types of snow—though

curiously no word for just plain snow. To them there is crunchy snow, soft snow, fresh snow, and old

snow, but no word that just means snow. The Italians, as we might expect, have over 500 names for

different types of macaroni. Some of these, when translated, begin to sound distinctly unappetizing,

like strozzapreti, which means "strangled priests", vermicelli means "little worms" and spaghetti

means "little strings." When you learn that muscatel in Italian means "wine with flies in it," you may

conclude that the Italians are gastronomically out to lunch, so to speak, but really their names for

foodstuffs are no more disgusting than English hot dogs.

A second commonly cited factor in setting English apart from other languages is its flexibility.

This is particularly true of word ordering, where English speakers can roam with considerable freedom between passive and active senses. Not only can we say "I kicked the dog," but also "The dog

was kicked by me"—a construction that would be impossible in many other languages. Similarly,

where the Germans can say just "ich singe" and the French must manage with "je chante," we can say

"I sing," "I do sing," or "I am singing." English also has a distinctive capacity to extract maximum

work from a word by making it do double duty as both noun and verb. The list of such versatile words

is practically endless: drink, fight, fire, sleep, run, fund, look, act, view, ape, silence, worship, copy,

blame, comfort, bend, cut, reach, like, dislike, and so on. Other languages sometimes show inspired

flashes of versatility, as with the German auf, which can mean "on," "in," "upon," "at," "toward,"

"for," "to," and "upward," but these are relative rarities.

At the same time, the endless versatility of English is what makes our rules of grammar so

perplexing. Few English-speaking natives, however well educated, can confidently elucidate the difference between, say, a complement and a predicate or distinguish a full infinitive from a bare one.

The reason for this is that the rules of English grammar were originally modeled on those of Latin,

which in the seventeenth century was considered the purest and most admirable of tongues. That it

may be. But it is also quite clearly another language altogether. Imposing Latin rules on English

structure is a little like trying to play baseball in ice skates. The two simply don't match.

A third supposed advantage of English is the relative simplicity of its spelling and

pronunciation. English is said to have fewer of the awkward consonant clusters and singsong tonal

variations that make other languages so difficult to master. In other languages it is the orthography, or

spelling, that leads to bewilderment. In Welsh, the word for beer is cwrw— an impossible

combination of letters for any English speaker.

In all languages pronunciation is of course largely a matter of familiarity mingled with

prejudice. The average English speaker confronted with agglomerations of letters like tchst, sthm, and

tchph would naturally conclude that they were pretty well unpronounceable. Yet we use them every

day in the words matchstick, asthma, and catchphrase. Here, as in almost every other area of

language, natural bias plays an inescapable part in any attempt at evaluation. No one has ever said,

"Yes, my language is backward and unexpressive." We tend to regard other people's languages as we

regard their cultures—with ill-hidden disdain. In Japanese, the word for foreigner means "stinking of

foreign hair." To the Czechs a Hungarian is "a pimple." Germans call cockroaches "Frenchmen,"

while the French call lice "Spaniards." We in the English-speaking world take French leave, but

Italians and Norwegians talk about departing like an Englishman, and Germans talk of running like a

Dutchman. Italians call syphilis "the French disease," while both French and Italians call con games

"American swindle." Belgian taxi drivers call a poor tipper "un Anglais." To be bored to death in

French is "etre de Birmingham," literally "to be from Birmingham". And in English we have "Dutch

courage," "French letters," "Spanish fly," "Mexican carwash'! (i.e., leaving your car out in the rain),

and many others. Late in the last century these epithets focused on the Irish, and often, it must be said,

they were as witty as they were wounding. An Irish buggy was a wheelbarrow. An Irish beauty was a

woman with two black eyes. Irish confetti was bricks. An Irish promotion was a demotion.

So objective evidence, even among the authorities, is not always easy to come by. Most books

on English imply in one way or another that English is superior to all others. In The English

Language, Robert Burchfield writes: "As a source of intellectual power and entertainment the whole

range of prose writing in English is probably unequalled anywhere else in the world." Yet, one can't

help wondering if Mr. Burchfield would have made the same generous assertion had he been born

Russian or German or Chinese. There is no reliable way of measuring the quality or efficiency of any

language. Yet there are one or two small ways in which English has a demonstrable edge over other

languages. For one thing its pronouns are largely, and mercifully, uninflected. In German, if you wish

to say you, you must choose between seven words: du, dich, dir, Sie, Ihnen, ihr, and euch. This can

cause immense social anxiety. In English we avoid these problems by relying on just one form: you.

In other languages, questions of familiarity can become even more agonizing. A Korean has to

choose between one of six verb suffixes to accord with the status of the person addressed. A speaker

of Japanese must equally wend his way through a series of linguistic levels appropriate to the social

position of the participants. When he says thank you he must choose between a range of meanings

running from the perfunctory arigato ("thanks") to the decidedly more humble makotoni go shinsetsu

de gozaimasu, which means "what you have done or proposed to do is a truly and genuinely kind and

generous deed." Above all, English is mercifully free of gender. Anyone who spent much of his or her

adolescence miserably trying to remember whether it is "la plume" or "le plume" will appreciate just

what a pointless burden masculine and feminine nouns are to any language. In this regard English is a

godsend to students everywhere.

English also has a commendable tendency toward conciseness, in contrast to many languages.

German is full of jaw-crunching words like Wirtschaftstreuhandgesellschaft (business trust company),

while in Holland companies commonly have names of forty letters or more, such as Douwe Egberts

Kon-mlijke Tabaksfabriek-Koffiebranderijen-Theehandal Naamloze Vennootschap (literally Douwe

Egberts Royal Tobacco Factory-Coffee Roasters-Tea Traders Incorporated; they must use fold-out

business cards). English, in happy contrast, favors crisp truncations: IBM, laser, NATO. Against this,

however, there is an occasional tendency in English, particularly in academic and political circles, to

resort to waffle and jargon. At a conference of sociologists in America in 1977, love was defined as

"the cognitive-affective state characterized by intrusive and obsessive fantasizing concerning

reciprocity of amorant feelings by the object of the amorance." That is jargon—the practice of never

calling a spade a spade when you might instead call it a manual earth-restructuring implement— and it

is one of the great curses of modern English.

Lecture Two

Languages in Contact

We cannot understand what a language is until we know its history. More than for most subjects,

history is the key to language, because the very fabric of a language - its vocabulary, its grammar, its

spelling, and so on - is a living record of its past.

So in the light of history, how can we begin to explain how English came to be what it is in the twentyfirst century? How did it come about that this language, once a tongue spoken by only a small number of

people in a rather small island, has become the most powerful international language in the world's

history? English is said to be a Germanic language, but why is it that more than half of its words are of

Latin or Romance origin? Why do we sometimes have a wide choice of words to express more or less the

same thing? And what is to blame for the chaotic English spelling? In the next few chapters we turn to

history to find the answer to these and other questions.

In a satire on eighteenth-century Englishmen's beliefs in national superiority, Daniel Defoe, probably

best known as the creator of Robinson Crusoe, described his mother tongue as 'Roman-Saxon-DanishNorman English'. To Defoe, English was but a mixture of the tongues spoken by different peoples who, in

the course of history, had invaded what is present-day England. Although he was being sarcastic, he did

have a point. Put simply, the making of English is a story of successive invasions.

Roman Britain

English was not always spoken in these islands. During the first millennium BCE, Celtic tribes

settled here, as they did virtually in all of western Europe, in successive ways of migration.

Although they were actually a mix of peoples speaking related languages, we will refer to them

collectively as Celts. It is important, though, that the Celts spoke a group of Celtic languages, and

were not a single national or ethnic group.

Some 2,500 years ago, Celtic languages were spoken widely across Europe. On the

European mainland, however, they were gradually replaced by other languages - for example, the

Romance family of languages, including French, Spanish and Italian. On a rough estimate, Celtic

languages are today spoken only by some one million people in the world. In the British Isles, th e

Celtic languages, which now survive as modern Welsh, Irish and Scottish Gaelic, have long been

fighting a rearguard action against English. The most viable of these survivors is Welsh with about

half a million speakers in Wales, where the vast majority of the population also know English. In

some western parts of the Republic of Ireland, efforts are made to sustain and revive Irish Gaelic and,

in the highlands of Scotland, Scottish Gaelic, but these efforts are having to fight hard to survive

against the insidious influence of English.

Over 2,000 years ago, the Roman general Julius Caesar led two expeditions to what he called

Britannia, the land of the Britons. Although Caesar’s most famous utterance was' Veni, vidi, vici' ('I

came, I saw, I conquered'), this certainly did not apply to his visits to Britannia: he soon went home

and never returned. The inhabitants of Britannia, collectively called Britanni by the Romans, kept

their political freedom and were not again troubled by Roman legions for almost 100 years. It was

later, in 43 CE, that Emperor Claudius ordered the invasion of Britain. Gradually the Roman legions

moved their frontiers further north and west, bringing almost all of what is now England under

Roman rule. During most of the period of occupation, the effective northern frontier was Hadrian's

Wall (named after the Roman Emperor Hadrian 76-138 CE), stretching between the present-day

northern English cities of Carlisle and Newcastle. Designated a World Heritage Site in 1987, the

remains of Hadrian's Wall, also known as the Roman Wall, proudly rank alongside the Taj Mahal

and other treasures among the great wonders of the world.

English

Frisian

West Germanic --------Flemish

Dutch

German

--Germanic

Norwegian

Icelandic

North Germanic(Norse)---

Indo-European

Danish

Swedish

East Germanic------------Gothic (extinct)

Gaelic---------------------Celtic------Britannic----------- -------

Scottish Gaelic

Irish Gaelic

Manx

Welsh

Cornish

Breton

-Romance---Latin--French/Italian/Spanish

In Roman Britain, towns grew up for a variety of reasons. The earliest settlements were built

by the army. In place-names like Lancaster, Leicester, Chester, Manchester and Winchester, the

element spelled caster, cester or chester is derived from the Roman word castra, meaning 'camp'. The

Romans brought a wide range of innovations to their British province, changing its landscape for

ever. Roman roads still criss-cross the landscape of England. The Latin word for a Roman road

was via strata ‘ paved road’ , which is the origin of English street German Strasse and Italian

strada. But, even though Britannia was under Roman rule for nearly 400 years, the Roman

occupation left hardly any lasting linguistic legacy. This is because the English language has its

roots in the next invasion, beginning in the fifth century, when Germanic tribes settled in the

country. Unlike the Romans they stayed for good and, in due course, they were to call their

language English.

The Anglo-Saxon Settlement

Like other parts of the Empire, Roman Britain had long been subject to attacks from external

enemies or 'barbarians' and, by the early fifth century, Roman legions were withdrawn and

Britannia was left to defend herself. According to later sources, in this desperate situation one of

the Celtic leaders enlisted the help of Germanic peoples who lived just across the North Sea on the

European mainland. It is reported that these semi-pirates expelled the enemies of the Britons, but

then turned their weapons against their hosts. Once settled, the newcomers supposedly invited

other continental tribesmen who arrived with swords at the ready.

This story rings true. Befriending one band of enemies to ward off another was an old

Roman tactic which the Britons no doubt adopted. But we shall probably never know exactly what

happened. It is clear, though, that from the middle of the fifth century and for

the next 100 years or so waves of migrating tribes from beyond the North Sea brought their

Germanic dialects to Britain. These tribes are traditionally identified as Angles, Saxons and Jutes.

Archaeology confirms that objects found in English graves are comparable to those from what is

now north Germany and the southern half of the Danish peninsula. To this list of tribes we should

add Frisians who, to this day, speak the continental language considered to be closest to English.

There was no sense of national identity among all these tribes, but they spoke neighbouring

Germanic dialects and were no doubt able to communicate with each other. For centuries there was no

collective name for the Germanic peoples who settled in Britain. The term Anglo-Saxon is sometimes

used to denote anything connected with English soil - language, people, culture - before the Norman

Conquest. But this is reconstruction, a convenient but vague label, used in contradistinction to Old

Saxons who remained on the continent. The Settlers called the native population wealas 'foreigners'

(from which the name Welsh is derived), while the Celts called the newcomers Saxons, regardless of

their tribe.

This term today appears in the modern Welsh words Saeson' the English ( people)' and Saesneg

' the English language.

Very few old Celtic words survived the invasions to leave their imprint on Modern English The

main survivors were the names of places and rivers. Place-names, such as Dover, Cardiff, Carlisle,

Glasgow, and London, and river names, such as the Avon, the Clyde, the Severn, the Thames , all

have some distant Celtic link. This scarce linguistic evidence has been used in support of the idea that

all Celts were driven out or killed. Most scholars however agree that the word ‘genocide’ is out of

place here, and that ‘ ethnic cleansing’ may have been more applicable. Many of the Celtic speaking

Britons retreated into the more remote and rugged regions that we now know as Cornwall, Wales,

Cumbria and the Scottish borders. Some of the Britons even emigrated across the Channel to

Armorica, as reflected in its present-day name Brittany, but the bulk of the British population

probably continued to live under Germanic rule and to speak their own language. Gradually the

Britons became absorbed into the Germanic population and eventually gave up their own language.

This process has continued to the present day. Cornish, the Celtic language of Cornwall, passed into

history in the late eighteenth century. The Celtic language of the Isle of Man, Manx, gradually gave

way to English in the nineteenth century, and the last Manx speaker is said to have died in the 1970s.

the tragic issue of ‘ language death’ is highly topical today, and these languages are now being

revived by enthusiastic antiquarians.

Old English was not very hospitable to foreign loans, which make up less than 5 per cent of

the recorded Old English words. But the traditionally held view that the Celtic languages made

virtually no impact on the language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons has recently been questioned. Some

linguists argue that, so far, Old English has been traced in a purely Germanic context and that the

social context in which English emerged has been overlooked. All Indo-European language families,

Celtic being one of them, share similarities, and where people intermingle it is realistic to consider

multiple origins of words or of other language features. Bilingualism is a recurrent theme in the

history of the English language. It existed not only at the time of the Germanic settlements but also

later at the time of the Scandinavian and Norman conquests. If these later invasions had not taken

place, the English language today might have sounded Frisian, the European language most

similar to English.

Christianity in the Isles

Roman Britain has been described as 'a religious kaleidoscope'. Christianity was introduced

into Britain in Roman times and, by the third century, British bishops were regularly attending

Church Councils. Constantine the Great, who was to convert the Roman Empire officially to

Christianity, was actually acclaimed emperor at York (then known as Eboracum) in 306. The Germanic

tribes, however, were pagans, worshipping their own gods, whose names, incidentally, survive in

Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. After the Germanic invasions, the Christian faith was

kept up only in Celtic areas such as present-day Cornwall and Wales. From Celtic Britain it was

introduced, in the fifth century, into Ireland where it developed in cultural and artistic isolation for

nearly 200 years. From this Celtic Church, Christianity was carried to the island of Iona on the

west coast of Scotland and, later, to the northern English kingdom of Northumbria.

In 596 Pope Gregory I sent a group of missionaries, headed by a monk named Augustine, to

the former Roman province of Britannia with instructions to convert the Anglo-Saxons to

Christianity. The kingdom of Kent, nearest to the continent, was swiftly converted and Augustine

became the first Archbishop of Canterbury. Since then Canterbury has remained the ecclesiastical

capital of England.

The missionaries promoted literacy and promoted translations from Latin into the native

tongue. A number of Christian ideas needed to be explained in simple terms to the new converts,

and Old English native words were applied to these new concepts: the Latin euangelium ( from

Greek evangelion) was rendered as gōdspell ‘good news’, later shortened to gospel; Dominus was

rendered as hlāfweard, literally ‘ guardian of the loaf’, from which we derive Lord ;the Latin

Infernum was rendered as Hell, an old Germanic word meaning ‘ hidden place’. In this way, the

language extended its own wordstock to meet new cultural needs.

But in other cases the translators found it easier to borrow words direct from Latin.

Altogether, there have been recorded some 400 Latin words in Old English introduced as a result of

the spread of Christianity. However, many of these loanwords, were not in general use and only a few

of them actually survive in modern English. The survivors are typically connected with religion or the

services of the church, such as these:

Latin

Old English

Modern English

abbas

abbod, abbud

abbot

apostolus

apostol

apostle

candela

candel

candle

cyriacum

cyrice

church

diabolus

dēofol

devil

discipulus

discipul

disciple

episcopus

biscop

bishop

martyr

martir

martyr

monachus

munic

monk

nonna

nunne

nun

papa

papa

pope

presbyter

prēost

priest

templum

temple

temple

While most of these words were originally Greek, they were adopted into English from

their Latin forms. Latin loanwords have been taken into English in virtually all periods of its

history. It is sometimes difficult to separate loanwords that were common Germanic from those that

came directly into English. For example, the Latin scōla was most likely borrowed into prehistoric

West Germanic on the European mainland, as it has since evolved into German Schule, Dutch

school, Swedish skola and Danish skole, as well as English school.

Most Latin words we find in Old English were introduced considerably later, in the tenth

century, through the great revitalizing of church life and learning known as the Benedictine

Revival.Many names of animals, plants and trees entered the language this way: for example, cypress,

ginger, lily, lobster, parsley, plant, purple and radish.

The Viking age

One summer day in the year 793 strange-looking ships were sighted out on the North

Sea. These strangers later would become all too well known and feared as the Vikings.

The origin of the word Viking remains a puzzle. In the Old Norse sagas, the word viking

(Old Norse víkingr) is generally restricted to brutal and unpleasant characters. It vas as late as the

nineteenth century that the word became the standard term for Scandinavian invaders. Contemporary

chroniclers called them by many names, including ‘heathens’ and 'pagans', but they were generally

referred to as either 'Northmen' or 'Danes'.

There were at least three phases of Viking activities, stretching over some 250 years: sporadic

raids, permanent colonization and political supremacy. In the first phase, from the late eighth century,

the attacks were basically hit-and-run affairs.

In the second phase, from 865 to 896, casual plundering gave way to permanent colonization. Until

the mid-tenth century there was no unified English monarchy but, in the mid-ninth century, there were still

four recognizable Anglo-Saxon kingdoms: East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria and Wessex. By the early

870s only the kingdom of Wessex (roughly corresponding to present-day England south of the Thames but

excluding Kent and Cornwall) remained intact. In Wessex the opposition was better organized than in the

other kingdoms. King Alfred of Wessex succeeded to the throne at the time of acute danger from Danish

invasion but, through a mixture of military success, tactful diplomacy and good luck, he managed to roll

back the Danish tide. Before Alfred's death in 899, he reached an agreement with the Viking leader

Guthrum to confine the Danes to the north and east of a diagonal line stretching roughly from London

to Chester, an area later known as the Danelaw, where Danish customs prevailed in contrast to the areas of

Anglo-Saxon law to the south and west. Guthrum agreed to leave Wessex alone and even accepted

Christian baptism, taking the English name of Athelstan.

However, this legacy of Alfred had a sad ending during the long inglorious reign of King Ethelred,

nicknamed 'the Unready'. In the years up to 1014, Viking activities entered the third and final phase of

political conquest, when King Sveinn of Denmark arrived with a Viking army, not for the extortion of

tribute, as was customary towards the end of the tenth century, but for the conquest of the kingdom. After

his death, the throne of England eventually passed to his son Cnut, the 'King Canute' who, according to

legend, sat on the shore and tried to stem the rising flow of the tides. Actually a wise and effective ruler,

Cnut was reconciled with the English, supported the Church and maintained peace in the country. After his

death in 1035, Denmark and England again became separate kingdoms, and in 1042 the old House of

Wessex was able to return to power. Politically, but not linguistically, this was the end of Scandinavian

influence in England.

The Vikings spoke dialects of Old Norse, the parent language of modern Danish, Swedish,

Norwegian and Icelandic. The Anglo-Saxons spoke dialects of Old English, which is the name we give

to the language from the middle of the fifth to the beginning of the twelfth century. Old English and Old

Norse were related Germanic languages, and many words were identical (folc/folk, hus 'house', sorg

'sorrow') or similar ( Old English fæder ‘father’, græs ‘grass’, wīf ‘woman’ corresponding to Old Norse

words fair, gras, víf).

About 1000 words in modern English can be traced back to Old Norse origins. The impact was

particularly great in English varieties spoken in northern England and in Scotland , where today we meet

dialect words such as these ( for comparison, modern Danish words are given in brackets): gate (gade)

‘street’, ‘road’ , ken (kende) ‘know’, lake (lege) ‘play’, neb (næb) ‘ beak, nose’. The borrowings from Old

Norse belong to the language of everyday life, reflecting close social contacts between the two peoples. As

the great Danish scholar , Otto Jespersen , once observed: ‘ An Englishman cannot thrive or be ill or die

without Scandinavian words; they are to the language what bread and eggs are to the daily fare’. In this

sentence, all four words in italics come from Old Norse.

In view of all the Scandinavian loanwords and place-names, it is likely that the Vikings and the AngloSaxons could understand each other - the two languages must have been to some extent mutually intelligible.

Wherever the Vikings settled and came into contact with another culture, they would ultimately be the ones

who lost most of their identity, being assimilated into the larger population around them. For the greater

part of the Viking age - roughly from 750 to 1050 -contacts, fierce or friendly, continued between

Scandinavians and Anglo-Saxons. Although the Scandinavian impact on English was considerable, Norse

did not survive much beyond the twelfth century In England. But interestingly, quite a few Norse

influences first appear in texts from the centuries after the Viking influence had ended. One very

common Norse loanword in English, the pronoun they , is an example of this time-lag.

Compared with the effects of the Norman Conquest, which was to follow, the Scandinavian

influence was less spectacular and revolutionary. But, as their name implies, the Normans themselves

were also 'men of the north', who had come originally from Scandinavia. This brings us to the next

important epoch in the history of English, when the language came under the dominant influence of French

- but French as spoken by the formerly Norse-speaking Normans.

THE NORMANS

The Viking adventurers who settled in Normandy in northern France during the early tenth

century were also baptised. They did not impose their oral vernacular, but were gradually assimilated

to the customs and language of the more centralised lands they colonised. In France, however, they

had to learn a language that was structurally very different from their own. That they did this, within

about four or five generations, is evidenced by the fact that it was a variety of French that they

imposed on England when, as Normans, they added this territory to their possessions by the military

Conquest of 1066. For the next three centuries or so, French was to be a living force in England, and

its influence continued to be felt, though less directly, for centuries after that.

The Norman invaders were few in number, but well-organised. They were interested in

territorial annexation and overcame the English by means of efficient military campaigns. The

superstructure of political and economic power -based on the ownership of land - was then almost

exclusively wrested from English hands and given to Norman friends of William the Conqueror. The

positions of power, in respect to both king and Church, were thus in the hands of French speakers, who

spent the next 150 years 'commuting' between their possessions on both sides of the Channel. It was

only when this ruling class lost its possessions in Normandy at the beginning of the thirteenth century

that it could begin to think of itself as English. Bу that time, French had become firmly established in

England as the High language of law, government, administration, and also, to some extent, literature

and religion. It was not until the fourteenth century that English was re-developed within these

domains. We need to distinguish, therefore, two phases of contact with French. The first involves the

Scandinavianised French of the Norman elite. Norman French was imposed by a ruling caste; but

since Latin continued in its spoken form in the Church, and as the written language of scholarship, the

linguistic situation after 1066 may be described as triglossic.

There has been some controversy about the extent to which this state of societal bilingualism

was realised at the individual level. Some have argued that French was very widely learned throughout

English society; others, that its use was very limited. One thing that we can be sure about is that

French did not displace English. Norman French did not offer linguistic unity or a prestigious, literate

language to linguistically diverse, uncentralised tribespeople. Neither did the Normans take much

trouble to encourage English people to learn their language. Norman French was exclusive, the

property of the major, and often absent, landowner.

While no wholesale language shift took place, it is probable that individual bilingualism came

to exist among certain social groups. The motivation for learning a second language, however, may

have been different in each case. Some groups would need to be bilingual, whereas for others

opportunities for contact with the other language would have been minimal.

We know that the

first language of the English monarchs was French until the end of the fourteenth century - long after

the Norman dynasty. It is also probable that the upper aristocracy were monolingual French-speakers

for a considerable time after the Conquest. It seems too that the upper aristocracy continued to use

French for a considerable time after 1066, although there is also evidence that some of them began to

learn English quite soon after that date. At the other end of the social scale, there is no reason to

believe that the ordinary people who worked the land spoke any language other than their local variety

of English. In a society overwhelmingly agrarian, this class would constitute the vast majority of the

population. During the period of French dominance, t hen, the regional variation of the Anglo-Saxon

era was intensified.

Not all the Normans were aristocrats, however. They brought with them people who could

administer their feudal estates; and these would have needed to be bilingual in their role as mediators

between overlord and land-labourers. There were also adventurers who became lesser landowners:

these were thinly spread in the countryside, and it is likely they would have adapted to local ways and

language, just as many of those who went on to settle in Ireland eventually learned Gaelic.

If at this time bilingualism was at all common, it was perhaps quite unremarkable, as it is in so

many parts of the world today. We do know that many Normans married English women, so it is likely

that children in the towns grew up as bilinguals.

French was also less strongly institutionalised in the domain of religion. Writings in English

emanated from the monasteries throughout the period of French dominance: the Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle was continued for nearly a century after the Conquest, and in following centuries didactic

religious texts circulated from mainly west midland sources. Sermons continued to be delivered in

English, although there is some evidence for French. It has been argued that most of the lesser clergy

were monoglot speakers of English, and that even in the monasteries newly founded by the Normans,

bilingualism, rather than French, was expected. As an institution of learning, then, the Church tended

to promote fluency in more than one language, as it had done in Anglo-Saxon times.

At the top of the social pyramid, however, Norman French was secure: a great deal of Norman

French literature was produced in England. About one hundred years after the Conquest, the first loanwords into English show how the language was associated with the instruments and offices of power:

prison and castle, cardinal and prior. But the full weight of loan-words comes later, during the second

phase of contact with French, this time with another variety of the language.

CULTURAL CONTACT WITH THE FRENCH OF PARIS

In 1204, the dukedom of Normandy was won by the king of France. While the kings of

England still retained possessions in more southerly parts of France, the descendants of the Norman

conquerors lost the sense of their ancestry. The ruling class of England became increasingly

Anglicised, but it maintained its contacts with the French of the kings of France, a monarchy which by

the end of the thirteenth century had become the strongest and most centralised in Europe.

From a sociolinguistic point of view, this second phase of contact with French is probably more

interesting than the first. We see language come to be regarded as a social symbol, as it is identified

with social groups of declared interests. The old Norman French is seen as provincial and

unfashionable, while the language of the French court is seen as the emblem of the most sophisticated

and prestigious culture in the contemporary world. To use this French, then, is to impress. In the eyes

of many, English had perhaps the aura of a peasant language. But among others, it became a marker of

what today we might call ethnicity.

Individual bilingualism would have been extensive during this phase. While the court retained

its devotion to French language and culture, the ruling class gradually acquired English. By the

fourteenth century, we begin to see the linguistic consequence of this process. English is saturated

with French loan-words, some of which have become such common currency that we tend to forget

their ancestry - words like pass, join, butcher, large. Some, like chase and guarantee, had even been

borrowed earlier, in the forms catch and warranty, from Norman French. The taste of the Francophile

court was reflected in much of the English poetry of this phase, which borrows French themes,

techniques, and language; and in so far as the English poet was brought up in this atmosphere, we can

best describe this period of contact as one of cultural bilingualism.

It is also the case that many English people learned French. The prestige of French as a marker

of high social status meant that some people learned it for its snob value. Since the Conquest, French

had been the medium of education, and schools were a means of acquiring the language. A

fourteenth-century writer, Higden, records that even people from the country busied themselves 'to

speke Freynsh', so they could sound like 'gentil men'. If there was a demand for the language, people

who could teach it had a vested interest in its continuance. Thus, we see in the same century edicts

enforcing French in the domains of education and religion. That a similar entrenchment existed in the

domain of law can be seen by the fact that 'Law French' was still in use, for some purposes, in the

seventeenth century. For a lawyer, the possession of a special language is a powerful weapon, as can

be seen in many multilingual societies today. The 'professionalisation' of law in the course of the

twelfth and thirteenth centuries meant that its practitioners could exploit the advantages of knowing a

special language: they could become parasitic on the people they were meant to serve.

If for some the French language meant social advancement, for others it aroused antagonisms.

Cultural contacts with France were an increasing source of tension in English life. The monarchy of

France came to be seen as a foreign power, whose interests often clashed with those of the people of

England. Moreover, while some kings of England waged long, costly, and fruitless wars against France,

others lavished the wealth of England on French favourites. Either was likely to upset baron, lesser

landowner, and merchant alike. Frenchmen, and the French language, were increasingly disparaged. From

its position as a tolerated language under the Normans, English became what socio-linguists might call a

promoted language, a mark of 'Englishness'.

The promotion of English was associated with gradual changes that had been taking place in

English society. The old feudal structure so successfully sustained by the Norman kings, the system of

obligations between king and aristocracy, was giving way to an economy based, not on land, but on

money. We see the emergence of new bases of power, new feelings of group loyalty. Alliances were made

between lesser landowners, who were making money out of raising sheep for wool, and the rising merchant

class in the towns, a pact institutionalised in the thirteenth century by the assembly that came to be

called Parliament. The founding of universities stimulated mobility, both geographical and social,

among certain sections of the population; and by the fourteenth century mobility had even spread to the

land-labourers, who could bargain for wages now that labour was scarce. By that time, the balance of

forces was beginning to favour an increasingly articulate, English-speaking merchant class. It was this

class, with London as its base, that spoke the basis of what came to be called standard English.

What's in a name?

This most remote province of the Roman Empire was called Britannia and its

people Britanni, from which come the modern forms Britain and British. Caledonia was

the Roman name for Scotland and, although outside the Empire, it was seen by the

Romans as a sphere of their influence. Hibernia, the Roman name for present-day

Ireland, was never part of the Roman Empire.

In 1707 the nation of Great Britain was formed by the Act of Union between England,

Scotland and Wales. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland was formed

in 1921 when the Irish Free State - later named the Republic of Ireland -became a separate

nation. The United Kingdom (or UK for short) includes the island of Great Britain,

comprising England, Scotland and Wales and, in addition. Northern Ireland, occupying

the north-east corner of the island of Ireland. Unofficially, the UK is often simply called

Britain, and its people are called British.

The British Isles is an unofficial but convenient geographical name. It refers to the

two large islands of Great Britain and Ireland, together with several islands and island

groups, such as the Isle of Man and the Orkney Islands. Many Irish people consider this

term British Isles a misnomer. For them, Ireland is not, nor should it be, in any sense

'British'.

The people of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland are British

citizens. Not everybody likes the modern label Briton or Britons, although this is the

correct way of referring to the ancient Celtic people of Britannia. Still, it is short and

practical to use in headlines:

BRITONS FLOCK TO THE SEASIDE

Brit is informal and can be derogatory. In older American slang the British are

called Limeys, a term originally applied to English sailors who were routinely supplied

with limes to prevent scurvy. In Australian and New Zealand slang Pom and Pommy are

common but can be offensive. It seems there is no neutral way of referring to the

inhabitants of the United Kingdom!

KING ALFRED THE GREAT

King Alfred is the only English monarch ever to be given the title 'Great', and justly so,

since he not only stemmed the Viking invasions, but laid the ground for a re-conquest, so that

his heirs eventually became kings of England. The West Saxon monarchs who succeeded him

gradually took over the Danelaw, paving the way for the unification of all England towards the

end of the tenth century. Under King Edgar, the country enjoyed two decades of peace up to

the 970s.

Alfred longed to improve the education of his people and set up what today might be

called 'a crash programme in education'. He started a court school and invited scholars from

abroad, arranged for the translation of Latin texts into English, and employed learned

churchmen to strengthen royal authority and establish a system of law. He and his team of

scholars were the founding fathers of English prose. If it had not been for Alfred, the history of

the English language might have taken quite a different turn - the standard language of Great

Britain might actually have been a Scandinavian tongue.

Lecture Three

GENERAL SURVEY OF THE

OLD ENGLISH VOCABULARY (5-15 centuries)

Examination of the origin of words is of great interest in establishing the interrelations

between languages and linguistic groups.

The OE vocabulary was almost purely Germanic; except for a small number of borrowings,

it consisted of native words inherited from PG or formed from native roots and affixes.

So from the point of view of its origin the Old English vocabulary can be divided into 2 groups:

I. native words or the so-called native element of the vocabulary.

II. borrowings (loan words) characterised also as the foreign element of the vocabulary. The

bulk of the Old English vocabulary consisted of native words, borrowings constituted but a

small part of the vocabulary.

Native words were not homogeneous in their origin. They are divided into the following 3

groups from the point of view of their reflection in other Indo-European Germanic and non-Germanic

languages:

1. Common Indo-European words:

Words belonging to the common IE layer constitute the oldest part of the OE vocabulary.

They go back to the days of the OE parent-language before its extension over the wide territories

of Europe and Asia and before the appearance of the Germanic group. They were inherited by PG

and passed into the Germanic languages of various subgroups, including English.

Among these words we find names of some natural phenomena, plants and animals,

agricultural terms, terms of kinship, etc.; verbs belonging to this layer denote the basic activities

of man; adjectives indicate the most essential qualities. This layer includes personal and

demonstrative pronouns and most numerals. OE examples of this layer are: eolh, mōna, trēōw,

næʒl, beard, brōðor, mōdor, sunu, dōn, bēōn, lång, ic, mīn, þæt, twā, etc. (MnE elk, moon,

tree, nail, beard, brother, mother, son, do, be, long, I, my, that, two).

2. Common Germanic words:

The common Germanic layer includes words which are shared by most Germanic languages,

but do not occur outside the group. Being specifically Germanic, these words constitute an

important distinctive mark of the Germanic languages at the lexical level. This layer is cer tainly

smaller than the layer of common IE words. Semantically these words are connected with nature,

with the sea and everyday life. Some of the words did not occur in all the OG languages. Their

areal of distribution reflects the contacts between the Germanic tribes at the beginning of their

migrations: West and North Germanic languages (represented here by OE, OHG and O Icel) had

many words in common.

Common Germanic Words in Old English

OE

OHG

Gt

O Icel

MnE

hand

hant

handus hond

hand

sand

sant

sandr

sand

eorþe

erda

airþa

jorð

earth

siggwan singva sing

sinʒan singan

findan

findan

finþan

finna

find

gruoni

græn

green

ʒrēne

steorfan sterban starve

scrēap

scâf

sheep

fox

fuhs

fox

macian mahhon make

3. Specifically OE words:

The third etymological layer of native words can be defined as specifically OE, that is words

which do not occur in other Germanic or non-Germanic languages. These words are few, if we

include here only the words whose roots have not been found outside English: OE clipian, brid,

boʒ, ʒyrl, hlāford, etc. (MnE call, bird, boy, girl, lord).

FOREIGN INFLUENCES ON OLD ENGLISH

The Contact of English with Other Languages. In the course of the first 700 years of its

existence in England it was brought into contact with at least three other languages, the languages of

the Celts, the Romans, and the Scandinavians. From each of these contacts it shows certain effects,

especially additions to its vocabulary. Nothing would seem more reasonable than to expect that the

conquest of the Celtic population of Britain by the Anglo-Saxons and the subsequent mixture of

their languages; that consequently we should find in the Old English vocabulary numerous

instances of words that that the Anglo-Saxons heard in the speech of the native population and

adopted.

Celtic Place-Names and Other Loanwords. When we come, however, to seek the evidence

for this contact in the English language, investigation yields very meager results. Such evidence

survives chiefly in place-names. The kingdom of Kent, for example, owes its name to the Celtic word

Canti or Cantion, the meaning of which is unknown, while the two ancient Northumbrian kingdoms of

Deira and Bernicia derive their designations from Celtic tribal names. Other districts, especially in the

west and southwest, preserve in their present-day names traces of their earlier Celtic designations.

Devonshire contains in the first element the tribal name Dumnonii, Cornwall means the 'Cornubian

Welsh', and the former county Cumberland (now part of Cumbria) is the 'land of the Cymry or

Britons'. Moreover, a number of important centers in the Roman period have names in which Celtic

elements are embodied. The name London itself, although the origin of the word is somewhat

uncertain, most likely goes back to a Celtic designation. The first syllable of Winchester, Salisbury,

Exeter, Gloucester, Worcester, Lichfield, and a score of other names of cities is traceable to a Celtic

source, and the earlier name of Canterbury (Durovernum) is originally Celtic. But it is in the names of

rivers and hills and places that the greatest number of Celtic names survive. Thus the Thames is a

Celtic river name, and various Celtic words for river or water are preserved in the names Avon, Exe,

Esk, Usk, Dover, and Wye. Celtic words meaning 'hill' are found in place-names like Barr (cf.

Welsh bar 'top', 'summit'), Bredon (cf. Welsh bre 'hill'), Bryn Mawr (cf. Welsh bryn 'hill' and mawr

'great') and others. Certain other Celtic elements occur more or less frequently such as cumb (a deep

valley) in names like Duncombe, Holcombe, Winchcombe; torr (high rock, peak) in Torr,

Torcross, Torhill; etc. Besides these purely Celtic elements a few Latin words such as castra,

fontana, fossa, portus, and vīcus were used in naming places during the Roman occupation of the

island and were passed on by the Celts to the English.

Outside of place-names, however, the influence of Celtic upon the English language is almost

negligible. The relation of the two peoples was not such as to bring about any considerable influence

on English life or on English speech. The surviving Celts were a submerged people. The AngloSaxon found little occasion to adopt Celtic modes of expression, and the Celtic influence remains the

least of the early influences that affected the English language.

Three Latin Influences on Old English. Unlike Celtic Latin was not the language of a

conquered people. It was the language of a highly regarded civilization, one from which the AngloSaxons wanted to learn. Contact with that civilization, at first commercial and military, later religious

and intellectual, extended over many centuries and was constantly renewed. It began long before the

Anglo-Saxons came to England and continued throughout the Old English period. For several hundred

years, while the Germanic tribes who later became the English were still occupying their continental

homes, they had various relations with the Romans through which they acquired a considerable

number of Latin words. Later when they came to England they saw the evidences of the long Roman

rule in the island and learned from the Celts additional Latin words that had been acquired by them.

And a century and a half later still, when Roman missionaries reintroduced Christianity into the island,

this new cultural influence resulted in a quite extensive adoption of Latin elements into the language.

There were thus three distinct occasions on which borrowing from Latin occurred before the end of the

Old English period, and it will be of interest to consider more in detail the character and extent of these

borrowings.

I. Continental Borrowing (Latin Influence of the Zero Period).

The first Latin words to find their way into the English language owe their adoption to the early

contact between the Romans and the Germanic tribes on the continent. Several hundred Latin words

found in the various Germanic dialects at an early date testify to the extensive intercourse between the

two peoples

The adopted words naturally indicate the new conceptions that the Germanic peoples acquired

from this contact with a higher civilization.

1) Next to agriculture the chief occupation of the Germanic tribes in the empire was war, and this

experience is reflected in words like camp (battle), segn (banner), pīl (pointed stick), weall (wall), pytt

(pit), stræt (road, street), mīl (mile), and miltestre (courtesan).

2)More numerous are the words connected with trade: cēap (bargain; cf. Eng., cheap, chapman)

and mangian (to trade) with its derivatives mangere (monger), mangung (trade, commerce), and

mangunghūs (shop), pund (pound), mydd (bushel), sēam (burden, loan), and mynet (coin). From

the last word Old English formed the words mynetian (to mint or coin) and mynetere (moneychanger).

3) One of the most important branches of Roman commerce with the Germanic peoples was the

wine trade: wīn (wine), must (new wine), eced (vinegar), and flasce (flask, bottle). To this period are

probably to be attributed the words cylle (L. culleus, leather bottle), cyrfette (L. curcurbita,

gourd), and sester (jar, pitcher).

4)A number of the new words relate to domestic life and designate household articles, clothing,

and the like: cytel (kettle; L. catillus, catinus), mēse (table), scamol (L. scamellum, bench, stool; cf.

modern shambles), teped (carpet, curtain; L. tapētum), pyle (L. pulvinus, pillow), pilece (L. pellicia,

robe of skin), and sigel (brooch, necklace; L. sigillum). Certain other words of a similar kind probably

belong here: cycene (kitchen; L. coquina), cuppe (L. cuppa, cup), disc (dish; L. discus), cucler (spoon;

L. cocleārium), mortere(L. mortārium, a mortar, a vessel of hard material), līnen (cognate with or

from L. līnum, flax), līne (rope, line; L. līnea), and gimm (L. gemma, gem).

5)The speakers of the Germanic dialects adopted Roman words for certain foods, such as

cīese (L. cāseus, cheese), spelt (wheat), pipor (pepper), senep (mustard; L. sināpi), cisten (chestnut

free; L. castanea), cires {bēam) (cherry tree- L. cerasus), while to this period are probably to be

assigned butere (butter; L. būtӯrum), ynne (lēac) (L. ūnio, onion), plūme (plum), pise (L.pisum, oea)

and minte (L. mentha, mint). Roman contributions to the building arts are evidenced by such words as

cealc (chalk), copor (copper), pic (pitch), and tigele (tile).

II. Latin through Celtic Transmission (Latin Influence of the First Period)

The Celts, indeed, had adopted a considerable number of Latin words - more than 600 have been

identified - but the relations between the Celts and the English were such, that these words were not

passed on. Among the few Latin words that the Anglo-Saxons seem likely to have acquired upon

settling in England, one of the most likely is ceaster. This word, which represents the Latin castra

(camp), is a common designation in Old English for a town or enclosed community. It forms a familiar

element in English place-names such as Chester, Colchester, Dorchester, Manchester, Winchester,

Lancaster, Doncaster, Gloucester, Worcester, and many others. Some of these refer to sites of

Roman camps, but it must not be thought that a Roman settlement underlies all the towns whose names

contain this common element. The English attached it freely to the designation of any enclosed place

intended for habitation, and many of the places so designated were known by quite different names in

Roman times. A few other words are thought for one reason or another to belong to this period: port

(harbor, gate, town) from L. portus and porta; munt (mountain) from L. mōns, montem; torr (tower,

rock) possibly from L. turris, possibly from Celtic; wīc (village) from L. vīcus. All of these words are

found also as elements in place-names. It is possible that some of the Latin words that the Germanic

speakers had acquired on the continent, such as street (L. strāta via), wall, wine, and others, were

reinforced by the presence of the same words in Celtic. At best, however, the Latin influence of the

First Period remains much the slightest of all the influences that Old English owed to contact with

Roman civilization.

III. Latin Influence of the Second Period: The Christianizing of Britain. The greatest influence

of Latin upon Old English was occasioned by the conversion of Britain to Roman Christianity

beginning in 597. The religion was far from new in the island, because Irish monks had been

preaching the gospel in the north since the founding of the monastery of Iona by Columba in 563.

However, 597 marks the beginning of a systematic attempt on the part of Rome to convert the

inhabitants and make England a Christian country. According to the well-known story reported by

Bede as a tradition current in his day, the mission of St. Augustine was inspired by an experience of

the man who later became Pope Gregory the Great. Walking one morning in the marketplace at Rome,

he came upon some fair-haired boys about to be sold as slaves and was told that they were from the

island of Britain and were pagans. “‘Alas! what pity,’ said he, ‘that the author of darkness is

possessed of men of such fair countenances, and that being remarkable for such a graceful exterior,

their minds should be void of inward grace?’ He therefore again asked, what was the name of that

nation and was answered, that they were called Angles. ‘Right,’ said he, ‘for they have an angelic face,

and it is fitting that such should be co-heirs with the angels in heaven. What is the name,’ proceeded

he ‘of the province from which they are brought?’ It was replied that the natives of that province were

called Deiri. ‘Truly are they de ira,’ said he, ‘plucked from wrath, and called to the mercy of Christ.

How is the king of that province called?’ They told him his name was Ælla; and he, alluding to the

name, said ‘Alleluia, the praise of God the Creator, must be sung in those parts.’” The same tradition

records that Gregory wished himself to undertake the mission to Britain but could not be spared. Some

years later, however, when he had become pope, he had not forgotten his former intention and looked

about for someone whom he could send at the head of a missionary band. Augustine, the person of his

choice, was a man well known to him. The two had lived together in the same monastery, and Gregory

knew him to be modest and devout and thought him well suited to the task assigned him. With a little

company of about forty monks Augustine set out for what seemed then like the end of the earth.

The third period of Latin influence on, the OE vocabulary began with the introduction of

Christianity in the late 6th c. and lasted to the end of OE.

Numerous Latin words which found their way into the English language during these five

hundred years clearly fall into two main groups:

(1) words pertaining to religion,

(2) words connected with learning.

The rest are miscellaneous words denoting various objects and concepts which the English

learned from Latin books and from closer acquaintance with Roman culture. The total number

of Latin loan-words in OE exceeds five hundred, this third layer accounting for over four

hundred words.

The new religion introduced a large number of new conceptions which required new names;

most of them were adopted from Latin, some of the words go back to Greek prototypes:

OE apostol

MnE apostle from L apostolus

from Gr apóstolos

antefn

anthem

antiphōna

antiphona

biscop

bishop

episcopus

episcopos

candel

candle

candēla

clerec

clerk

clēricus

klerikós

dēofol

devil

diabolus

diábolos

mæsse

mass

missa

mynster

minster

monastērium

munuc

monk

monachus

monachós

cyrice < Gr. kuriacon (ÏÇñ³ÏÇ) “of the Lord”

Mn.E. church

English “The house of the Lord”

Armenian “The day of the Lord”

To this list we may add many more modern English words from the same source: abbot,

alms, altar, angel, ark, creed, disciple, hymn, idol, martyr, noon, nun, organ, palm, pine

('torment'), pope, prophet, psalm, psalter, shrine, relic, rule, temple and others.

After the introduction of Christianity many monastic schools were set up in Britain. The

spread of education led to the wider use of Latin: teaching was conducted in Latin, or consisted

of learning Latin. The written forms of OE developed in translations of Latin texts. These conditions

are reflected in a large number of borrowings connected with education, and also words of a more

academic, "bookish" character. Unlike the earlier borrowings scholarly words were largely

adopted through books; they were first used in OE translations from Latin, e.g.:

OE scōl

NE school

L schola (Gr skole)

scōlere

scholar

scholāris

māʒister

master, ‘teacher’

magister

fers

verse

versus

dihtan

‘compose’

dictare

Other modern descendants of this group are: accent, grammar, meter, gloss, notary, decline.

A great variety of miscellaneous borrowings came from Latin probably because they indicated

new objects and new ideas, introduced into English life together with their Latin names by those

who had a fair command of Latin: monks, priests, school-masters. Some of these scholarly words

became part of everyday vocabulary. They belong to different semantic spheres: names of trees

and plants - elm, lily, plant, pine; names of illnesses and words pertaining to medical treatment cancer, fever, paralysis, plaster; names of animals - camel, elephant, tiger; names of clothes

and household articles - cap, mat, sack, sock; names of foods - beet, caul, oyster, radish;

miscellaneous words - crisp, fan, place, spend, turn.

From the beginning, the English did not hesitate to hybridize by combining Latin roots with

native prefixes or suffixes and by forming compounds consisting of one Latin and one English element.

Thus OE bemūtian 'to exchange for' has an English prefix on a Latin stem (L. mutare). OE

candeltrēow 'candelabrum' has a Latin first element and an English second element (trēow 'tree').

Latin influence on OE vocabulary is also occasionally reflected in calques, or loan translations, in

which the semantic elements of a foreign word are translated element by element into the borrowing

language. For example, Latin unicornis 'unicorn' was loan-translated as ānhorn 'one horn', and OE

tofealdan 'to come to land' is a calque of Latin applicare. Probably the best-known OE calque is

godspell 'gospel', literally "good news," from Latin evangelium.

Good examples of translation-loans are the Germanic names of days.

L. Lunnae dīes =

O.E. Mōndan dæʒ “ day of the moon”

L. Martis dīes =

O.E. Tiwes dæʒ

Tiw was a Germanic God identified with the Roman Mars

L. Mercuri dīes =

O.E. Wōdnes dæʒ

Woden was a Germanic God.

L. Iowis dīes =

O.E. þūnres dæʒ

L. Jupiter

=

O.E. þūnr

L. Veneris dīes =

O.E. Friʒe dæʒ

Friʒe was a Germanic goddess corresponding to Roman Venus

L. Sōlis dīes =

O.E. Sunnan dæʒ “ day of the sun”

The only exception was Saturday.

L. Saturni dīes =

O.E. Sætern dæʒ

The number of translation-loans was great in O.E. religious literature.

In English history the Middle English period is marked by 2 important historical events, which

influenced the further development of the English language. These were the Scandinavian invasions on

the one hand and the Norman Conquest on the other hand. Due to these conquests English came into

contact with 2 different languages: Scandinavian dialects (Danish, Swedish, Norwegian) and French,

and underwent the influence of the languages. Especially important was the influence of Scandinavian

dialects as the fusion of English with the Scandinavian dialects brought about considerable changes in

the grammatical structure, especially in English morphology. (The process of reduction of unstressed

syllables was strengthened and accelerated under the Scandinavian influence).

The Relation of the Two languages. The relation between the two languages in the district

settled by the Danes is a matter of inference rather than exact knowledge. Doubtless the situation was

similar to that observable in numerous parts of the world today where people speaking different

languages are found living side by side in the same region. Although in some places the Scandinavians

gave up their language early there were certainly communities in which Danish or Norse remained for

some time the usual language. Up until the time of the Norman Conquest the Scandinavian language in

England was constantly being renewed by the steady stream of trade and conquest. In some parts of

Scotland, Norse was still as late as the seventeenth century. In other districts in which the prevailing

speech was English there were doubtless many of the newcomers who continued to speak their own

language at least as late as 1100 and a considerable number who were to a greater or lesser degree

bilingual. The last-named circumstance is rendered more likely by the frequent intermarriage between

the two peoples and by the similarity between the two tongues. The Anglian dialect resembled the

language of the Northmen in as number of particulars in which West Saxon showed divergence. The

two may even have been mutually intelligible to a limited extent. Contemporary statements on the

subject are conflicting, and it is difficult to arrive at a conviction. But wherever the truth lies in this

debatable question, there can be no doubt that the basis existed for an extensive interaction of the two

languages upon each other, and this conclusion is amply borne out by the large number of

Scandinavian elements subsequently found in English.

SCANDINAVIAN BORROWINGS AND THEIR INFLUENCE ON

THE ENGLISH VOCABULARY

Scandinavian borrowings present great variety as to their semantics though words of everyday

life prevail over any other words. Chronologically, the first significant new source of loanwords in

ME was Scandinavian. (At this time, the differences among Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian were so

slight that it is unnecessary to try to distinguish them; hence we use the more general terms Norse or

Scandinavian.) Many of the Scandinavian words that first appear in writing during ME were actually

borrowed earlier, but, particularly in a society with a low literacy rate, there is a lag between use in

speech and first appearance in writing. When they were written down, it was usually first in the North

and the East Midlands, those regions with heaviest Norse settlements. Only later did they spread to other

areas of England.

The listing below is not exhaustive. The Scandinavian element in English amounts to over 650

words.

Nouns –

birth, booth, bull, crook, dirt, down, fellow, freckle, gap, guess, husband,

kid, leg, link, loan, root, skill, score, sky, tidings, trust, window.

Adjectives awkward, flat, ill, loose, low, meek, odd, rotten, scanty, sly, ugly, wrong.

Verbs –

to busk, to call, to cast, to crawl, to die, to drop, to gasp, to glitter, to lift, to

nag, to raise, to scatter, to screech, to take.

A quick perusal of these lists reveals that almost all these words are so common. English

today, so native in appearance, that it is hard to believe that they are loans from another language. Part

of their familiarity is explainable by the fact that they have been in the language for so long that they

have had plenty of time to become fully assimilated. Further, Scandinavian is so closely related to

English that these loans "feel" like English.

Some of the Norse loans (such as both, call, and take) express such basic concepts that we feel

that they must be native words, that Old English could not have done without them. Old English did

have its own terms for the concepts, but, unlike the majority of ME loans from French or Latin, Norse

loans often supplanted rather than supplemented native vocabulary. Thus Norse call replaced OE hātan,

both replaced OE bā, and take replaced OE niman and fōn. In other instances, the Norse loan took over

only part of the domain of the native English word, while the English word survived in a narrowed

usage. For example, ON sky replaced OE heofon as the general term for the upper atmosphere, but

heaven survives, especially in the sense of "dwelling-place of God." Occasionally, both the native

word and the Norse loan survive as almost complete synonyms; few people could specify any distinct

difference in meaning between Norse crawl and native English creep.

In addition to its contributions to the general vocabulary, Norse introduced a number of new

place-name elements into English, especially into the areas heavily settled by the Scandinavians.

Chief among these were –beck ‘brook’, -by ‘town’, -dale ‘valley’, -thorp ‘ village’, -thwaite

‘piece of land’, and –toft ‘piece of ground’: Griezebeck, Troutbeck, Thursby, Glassonby,

Knarsdale, Uldale, Braithwaite, and Seathwaite.

Finally, Norse influence was heavy at about the time the English began to us surnames, so

Norse was able to give English the common surname suffix -son. The suffix proved so popular that it

was attached not only to first names of Norse origin (Nelson, Anderson), but also to native English

names (Edwardson, Edmundson) and even to French names (Jackson, Henryson). English did not,

however, adopt the Scandinavian practice of using -datter 'daughter' as a surname suffix for females.

The Scandinavian words that made their way into English were not confined to nouns and

adjectives and verbs but extended to pronouns, prepositions, adverbs, and even a part of the verb to be.

Such parts of speech are not often transferred from one language to another. The pronouns they, their,

and them are Scandinavian. Old English used hīe, hiera, him. Possibly the Scandinavian words were

felt to be less subject to confusion with forms of the singular. Moreover, though these are the most

important, they are not the only Scandinavian pronouns to be found in English. A late Old English

inscription contains the Old Norse form hanum for him. Both and same, though not primarily

pronouns, have pronominal uses and are of Scandinavian origin. The preposition till was at one time

widely used in the sense of to, besides having its present meaning; and fro, as the equivalent of from,

survives in the phrase to and fro. Both words are from the Scandinavian. From the same source

comes the modern form of the conjunction though, the Old Norse equivalent of OE þēah. The

Scandinavian use of at as a sign of the infinitive is to be seen in the English ado (at-do) and was more

widely used in this construction in Middle English. The adverbs aloft, athwart, aye (ever), and seemly,

and the earlier heþen (hence) and hweþen (whence), are all derived from the Scandinavian. Finally the

present plural are of the verb to be is a most significant adoption. While we aron was the Old English

form in the north, the West Saxon plural was syndon (cf. German sind), and the form are in Modern

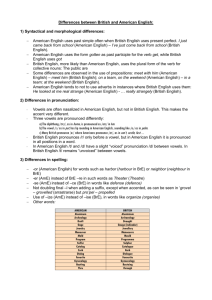

English undoubtedly owes its extension to the influence of the Danes. When we remember that in the