Belief and Hope in Hospitals – The Work of Chaplains and Imams in

advertisement

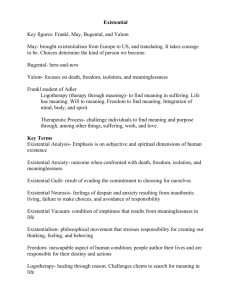

Belief and Hope in Hospitals – The Work of Chaplains and Imams in a Secular Context This presentation concerns the work of chaplains and imams in a secular setting like the hospital. It builds upon several interviews that I have conducted with both imams and chaplains. The interviews are part of my newly initiated PhD project, which focuses on cancer patients in palliative care with either a Muslim or a Christian background. A Qualitative Study Related to the PhD Project The Religious Resources of Muslim and Christian Cancer Patients in Palliative Care The overall aim of the PhD project called The Religious Resources of Muslim and Christian Cancer Patients in Palliative Care is to shed light on how severely ill cancer patients experience existential distress. Furthermore the objective is to gain knowledge about how severely ill cancer patients with either a Muslim or Christian background approach their concerns and distress by drawing on the language or the actions of their religious traditions. And finally the project strives to obtain evidence on how the need for support is being meet by the professional healthcare takers. My hypothesis underlying this research is that if the patients have been religious before being diagnosed with cancer, they might have access to other resources that could influence the ways in which they see their illness and help to cope with their life situation e.g. by framing it as the will of God. Mapping the way: -Interviews with patients, relatives & professionals -Observations of the cancer patients’ conversations with the chaplain or the imam -Test of religiosity with Q Sort-Faith -Comparison of religious coping strategies So mapping the way of the PhD project, these mentioned areas will be covered to shed light on my interest in finding out which problems and concerns are present when being severely ill and dying. First of all I will use a multi-perspective approach involving interviews with cancer patients, their relatives and professional caretakers, like the chaplains and the imams. So this is some of the data I am presenting to you today. This data will later be supplied with observations done at hospital settings and at home of the patients being interviewed, if possible. The observations of the conversation will be filmed, if both the chaplain/imam (and in some cases the doctors) and the patient allow it. The Q Sort-Faith test (evolved by Prof. David Wulff attending the conference) is being validated among cancer patients in rehabilitation. If relevant, the test is used to compare the patient’s and the chaplain’s worldview to evaluate, whether sharing the same values or belief support the feeling of being helped by talking to the chaplain or the imam. Due to the obtained knowledge it will be possible first to make a comparison of the different religious needs and resources among Christian and Muslim cancer patients in palliative care, and thereby providing evidence-based knowledge for supporting the existential and religious needs of cancer patients in palliative care. So these are the questions we will address during the presentation to gain a little insight into the work of chaplains and imams in a secular setting. The existential concerns and religious needs of cancer patients - What do we mean by ‘existential and religious needs’? - What do we know about the patients and their needs? - What needs are the chaplains working with? - How do they approach the patients’ belief and hope? So what are existential concerns? Irvin Yalom, an American psychiatrist, points to existential concerns as being related to certain conditions that we cannot change. We all must die In decisive times we are alone We have the freedom to choose our life We struggle to find meaning in life (Yalom, 1980) According to Prof. Bo Jacobsen the existential conditions express themselves in what he terms as the dilemmas of life. These dilemmas take form as opposites, contrasting each other as different modes of life that we are challenged to balance. The dilemmas are Happiness vs suffering how can I strive for happiness when I know there will be suffering? Love vs aloneness can I overcome the condition of being alone in a loving relationship? Good vs bad luck how can I grow instead of being stuck when confronted with bad times Fear of death vs engagement in life how can I engage fully in life when I know, I’ll die? Freedom of choice vs obligations how can I change the reality I’m born to a positive basis Life purpose vs meaninglessness how can I find meaning in life despite the chaotic conditions of the world? So what I mean by ‘existential concern’ in this context is -What is important to the existence (of the individual) in relation to hope, meaning, purpose, and values. Further on my definition of religious needs relies on the act where these existential concerns are related to a religious meaning system. If so the needs for support, guidance, consolation etc. will be rendered as a religious. What do we know about Danish cancer patients’ existential needs? Kræftpatientens verden. En undersøgelse af hvad danske kræftpatienter har brug for. Grønvold, M. et al. (2006). Bispebjerg: Forskningsenheden Pall. Med. Afd. The research project The world of the cancer patients undertaken by Mogens Grønvold et al. el in 2006 shows that 17% of the participating cancer patients feel that the illness has given rise to both religious and existential concerns. Moreover from within this group 32 % express that their existential and religious concerns are not sufficient meet by the health care professionals. So there are existential and religious needs that are not being taken care of. In the study Existential thoughts and religious life of Danish patients by Nadja Ausker, Peter la Cour, Christian Busch and more inUgeskrift for Læger, 2008 May 19; 170 (21): 1828-33, results are pointing to changes in the existential and religious needs of patients. This sociological research from 2008 is conducted in the Capital Region of Denmark (Rigshospitalet). The study shows that existential and religious thoughts are more widespread among the hospitalized patients than previously assumed. Due to the questionnaire there is a tendency to rethink one’s life and seek purpose and meaning and 62% of the patients answered that they pray, meditate or the like during their hospitalized. There is also a higher activity to practice “the established kind of religiosity” where 22% felt a greater need to pray, go to church or find consolation in religion. Palliative Needs in Danish Patients with Advanced Cancer. The research shed light on the symptoms and problems that are experienced as the most tiresome by palliative patients and what kind of needs are unmet. Here tiredness, problems related to physical activities and worries are rated the highest. As the category of worries is undifferentiated it might be where the existential concerns are present. Who supports existential and religious needs? Most patients would like to talk with their doctors about existential issues. But international studies show that the average time for a consultation at the doctor differs from Germans who have 7,8 min. to spend, where the English have about 9 min, going to the Swiss’ having up till 14 min. Other studies have shown that patients feel responsible for keeping time. So they can’t take up time consuming issues like fear of death or dying. So they may end up talking with the chaplain instead ! Talk with the chaplain: 23% No contact person: 20% Want talk with the doctor: 37% But there is no guarantee of getting to talk to the chaplain or the imam because of having existential concerns or religious needs. The rules for visiting patients are unclear and the chaplains might have to find the patients in need themselves, and this might be difficult because of the shortened lengths of the stay at hospitals. ’How did you decide which patients to visit this week?’ Fitchett, G. & Risk, J.L (2009) So what do people talk with the chaplains about? The sociologists Susan & Peter Strang conducted a nationwide questionnaire in Sweden among hospital chaplains in 2002. Among other things they asked the chaplains to list the 3 most frequently asked questions in relation to life-threatening disease. The main categories focused on by the patients were: meaning, death, illness, relationships, and religion. When talking to the chaplains the patients ask questions in relation to these subjects: Frequent question posed to chaplains and imams: Meaning/story of life - Why? Death and dying - What happens? Illness and pain - What help can I get? Relationship and separation - How will they manage? Religious issues - Why does God make me suffer? Other questions - How can I trust the doctors? Existential vs religious needs The patients do not contact the chaplains primarily to discuss spiritual or religious questions, but rather to discuss questions about their love for and care of their families and about the meaning of suffering. (Wright, 2001) Within a patient group of colorectal cancer, 93% of the questions dealt with the meaning of life and its value in general terms. (Klemm et al., 2000) Secularized values founded on the rationality of science, have to a large extent replaced religious beliefs in Sweden as well as in many other secularized countries. (Kallenberg, 2000) So evidence shows that many of the issues being addressed in the conversations with the chaplains (and maybe also with the imams?) are existentially orientated. So how do we distinguish between pastoral care and psychological therapy? Some differences between pastoral care and psychotherapy: Psychotherapy involve - kinds of treatment - professionally educated therapist - orientation towards problems or symptoms - criteria of success - choice of therapeutic approach Pastoral care involves - support of psychic and spiritual growth - religious worldview - practiced by religious professionals - religious institution behind - focus on the individual - no criteria of success Muslim pastoral care Islamic concepts: Ikhlaq/-iat: Having a good character Iyadah: The obligation to visit the ill Rifq: Showing exemplary care The most evident difference between Muslim/Christian pastoral care and psychotherapy is the context to which the experiences are ascribed. Which kind of narratives does the person tell their life story into. Is it secular or religious? And how do the chaplain and the imam approach the existential concerns when they themselves are religious and the patient is maybe not? To shed light on these issues I have interviewed six chaplains and two imams, one working regularly in hospital settings and the other not. I asked them to tell me about their experience of the existential concerns and religious needs of the patients, they normally deal with. Furthermore I asked them whether they characterize the patients as mainly religious or not. Finally I asked them to reflect upon the kind of religious elements they use in their work to help the patients, which can be termed as actions related to their own belief. The chaplains stated that only a few of the patients, they meet, are deeply religious. But if they are, it is often elderly people. One chaplain characterized the religious patients as those who had either found comfort in God and use the Bible and the hymns to cheer up and to praise God. Or those who are troubled by the change and the decay they experience and might suddenly not be able to find God. But most of the patients speaking to the chaplains are not characterized to be religious in this sort of way. Instead they bring existential concerns about meaning-making to the table and want to discuss their worries about their loved ones, their fear of death and dying and the meaning of being severely ill and leaving the world behind. In this regard my findings are very close to those found in the study of Sprang and Sprang. Even though the issues at hand are not termed to be religious, a younger chaplain makes it clear that he strives to be whatever kind of chaplain the patient is in need of! So they talk about that ’The coffee is terrible and those kind of things, but AAB (a football team) lost again, so... And the family that came to visit and their pain. And sometimes we end up with something that has like a religious content. And then you can say that I look at my role as a chaplain, as a way to be a chaplain in the way that people need it. So if Peter wants to talk about those things because it is easy, this is what we do!’ Whatever strategies are used, the purpose is to accompany the patient in his or her search of relief or meaning. In this process the chaplain often talks with the patient about faith and values, expressed through things related to everyday life. A chaplain expresses it this way: ’We don’t talk with people about their values. They don’t say ’Now my values are broken down!’ But they say ’I’m afraid to lose my children, I’m afraid to die and go away from my children, I’m afraid not to be able to manage my job, I’m afraid of...’ And that is to talk about values! Values are not something abstract, they can be understood as abstractations, but you don’t talk about it abstractly, you talk about it as something concrete.’ In this way whatever is relevant and meaningful to the person can be an issue for the conversation. I view this approach with an openess to the existential content of the conversation as part of the belief of the chaplain. Even though the belief of the chaplain might not be thematized it is actualized by the approach to the patient as an individual in need of a fellow human being. The role of the care taker can be different and the belief can be more emphasized. This is the case with one of the imams I spoke to. He said: It goes without saying that when people come to me, it’s not because they want me to give them some pills! I try rather to give them what I believe they are looking for, namely a way of entering that unseen dimension that surrounds faith, and faith’s way of addressing sickness and the self. My starting point is what people want from me, otherwise they won’t seek me out. And I have to take it from there. And, having come a long way, I have to say that my impression is that it is working pretty well. The approach to meaning-making as inspired by existential thought or by relying on ones belief seems to differ from some of the chaplains and the imam, where in the last case a belief in fate may be present. I once was sitting with my own daughter in fact, who was just diagnosed with cancer. And that day she was diagnosed, she went quiet for a few seconds, and then she said: “Alhamduallah! I thank Him who created me”. She was sixteen or seventeen at that time. And I was so happy that she said that! Because I knew then that she would be able to deal with it! When she handled things in that way and her immediate response was “Alhamduallah”, so she was ready. So he emphasize that importance of belief by saying: And that is one of the most vital things in a person’s struggle with sickness and with the healing process that they have inside of themselves, exactly what they need. If they don’t have it, then even a relatively minor disease can bring down a strong person. But if one has it, then even a major disease cannot bring down a smaller person. So to sum up both the chaplain and the imams will meet the need for consolidation by talking to the patient about values, beliefs or aspects related to everyday life that is of importance for the individual. The study show a great variation in the ways in which the chaplain and the imams engage with their own belief and use this to support the patients’ belief system and meaningmaking process. Apparently it makes a difference which belief the patient has and which belief the chaplain and the imam represent. Most chaplains emphasize the existential concerns that relate to theological themes that is experiences of meaninglessness, the doubts of the patients, and the present of God through important relations. Others like one of the imams orientate themselves more directly to faith and believe in God almighty and interpret the situation as God’s will. So the roles of the chaplain and imams can differ considerably related to their way of practising their belief. So they can conceive themselves as fellow believers, as religious therapists, as carriers of faith (helping to establish or enhance a relationship with God) or as supportive conversational partners helping people under stressful circumstances to cope with their challenges.