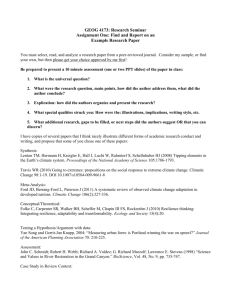

APUBEF_complete_2003

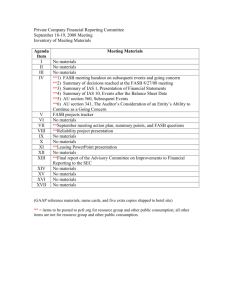

advertisement