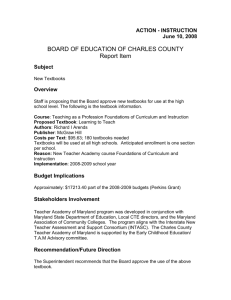

A strategy for implementing a new educational

advertisement