Film Editing Techniques: A Study Guide

advertisement

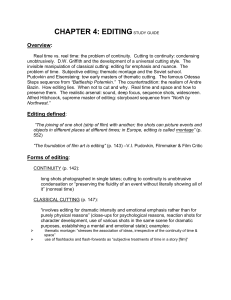

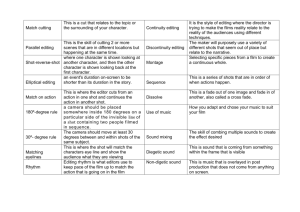

STUDY GUIDE CHAPTER 4: EDITING Overview: Real time vs. reel time: the problem of continuity. Cutting to continuity: condensing unobtrusively. D.W. Griffith and the development of a universal cutting style. The invisible manipulation of classical cutting: editing for emphasis and nuance. The problem of time. Subjective editing: thematic montage and the Soviet school. Pudovkin and Eisenstein: two early masters of thematic cutting. The famous Odessa Steps sequence from “Battleship Potemkin.” The counter tradition: the realism of Andre Bazin. How editing lies. When not to cut and why. Real time and space and how to preserve them. The realistic arsenal: sound, deep focus, sequence shots, widescreen. Alfred Hitchcock, supreme master of editing: storyboard sequence from “North by Northwest.” Editing defined: “The joining of one shot (strip of film) with another; the shots can picture events and objects in different places at different times; in Europe, editing is called montage” (p. 552) “The foundation of film art is editing” (p. 143) –V.I. Pudovkin, Filmmaker & Film Critic Forms of editing: CONTINUITY (p. 142): long shots photographed in single takes; cutting to continuity is unobtrusive condensation or “preserving the fluidity of an event without literally showing all of it” (nonreal time) CLASSICAL CUTTING (p. 147): “involves editing for dramatic intensity and emotional emphasis rather than for purely physical reasons” (close-ups for psychological reasons, reaction shots for character development, use of various shots in the same scene for dramatic purposes, establishing a mental and emotional state); examples: thematic montage: “stresses the association of ideas, irrespective of the continuity of time & space” use of flashbacks and flash-forwards as “subjective treatments of time in a story [film]” SOVIET MONTAGE AND THE FORMALIST TRADITION (p. 163): stressed “that the ideas in cinema are created by linking together fragmentary details to produce a unified action; through the juxtaposition of shots, new meanings can be created, and the meanings, then, are in the juxtapositions, not in one shot”; example, he linked together a shot of Moscow’s Red Square with a shot of the American White House, close-ups of two men climbing stairs with another close-up of two hands clapping. Projected as a continuous montage: “transitional sequences of rapidly edited images, used to suggest the lapse of time” REALISM and EDITING (p. 178): “believed that in the cinema there are many ways of portraying the real; the essence of reality lies in its ambiguity; filmmakers whose films reflect a sense of wonder before the mysteries of reality and that distortion of reality, thematic montage, violate the complexities of reality”; examples: use of deep-focus photography (a technique that allows all images to remain in focus, from close-ups to infinity) and lengthy takes use of panning, craning, tilting or tracking rather than editing to individual shots Conclusion: “Some questions we ought to ask ourselves about a movie’s editing style include: How much cutting is there and why? Are the shots highly fragmented or relatively lengthy? What is the point of the cutting in each scene? To clarify? To stimulate? To lyricize? To create suspense? To explore and idea or emotion in depth? Does the cutting seem manipulative or are we left to interpret the images on our own? What kind of rhythm does the editing establish with each scene? Is the personality of the filmmaker apparent in the cutting or is the presentation of shots relatively objective and functional? Is editing a major language system of the movie or does the film artist relegate cutting to a relatively minor function? Key Example from the Text: Hitchcock’s “North by Northwest” Storyboard Version” (p. 191) Essential Viewing: Melies’ “A Trip to the Moon” Scorsese’ “Raging Bull” Reed’s “The Third Man” Welles’ “The Lady from Shanghai” Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin” Hitchcock’s “North by Northwest” Lumet’s “Dog Day Afternoon” Scott’s “Blade Runner” Zinneman’s “High Noon” Keaton’s “The General”