HST 777 MEDICINE FROM ANTIQUITY TO 1500 CE Fall 2012

advertisement

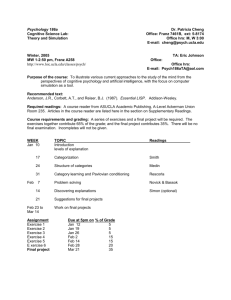

HST 777 MEDICINE FROM ANTIQUITY TO 1500 CE Fall 2012 Instructor: Jaipreet Virdi History Department, Ryerson University Jorgenson Hall Room 528 Email: jvirdi@ryerson.ca Office Hours: Tuesdays 10-12; Wednesdays 1-2 Lectures: Section 1: Mondays 11-1 (SHE 660) Section 2: Wednesdays 11-1 (SHE 560) Seminars Section 1: Tuesdays 9-10 (SHE 554) Section 2: Mondays 1-2 (SHE 662) The dread of disease, physical pain, and mental suffering has always loomed large in human experience. How did people in the past react to sickness? What kinds of diseases affected people’s lives, and what approaches were taken to hold diseases at bay? This course covers diseases and medical practice from antiquity to AD 1500. It is set in the context of the Near East, Greek and Roman society, the Islamic world, and Medieval Europe. An underlying theme is the complex interplay between disease, patient, and physician. 1 Course Description Throughout the course, we will analyze and evaluate the social, intellectual, and cultural processes of the medical heritage, covering a variety of themes, including: -The epistemology of diseases: what theoretical models were constructed to explain the onset of disease and illness and how widespread were these models? -Learned knowledge and intellectual exchange: how did texts, expertise, institutions, and authority define and construct the practice of medicine? -The cultural history of the body: in what ways did depictions of (gendered, defective, disabled) bodies shape an understanding of sex, childbirth, and the role of the physician? -The social history of illness: how was disease experienced and how did illness define the relationship between patient and practitioner? Course Objectives & Learning Outcomes This course is designed for you to gain knowledge of major developments in medical theory and practice. You will learn how to advance your skills in critical thinking and reading, becoming familiar with scholarship on the history of medicine. You will also learn how to read and analyze various primary source materials within their cultural contexts and think critically about their basic assumptions and conceptual frameworks. By the end of the course, you should be able to: -understand and outline the features of humoral medicine and why it was such a dominant theory -understand how different types of institutions contributed to the formation of medical knowledge -explain how religious, social, political, and intellectual factors shaped and governed the practice of medicine, particularly within the structure of the ‘medical marketplace’ -utilize primary sources critically for analyzing broader themes discussed in the course Organization This course is divided into 2-hour lectures and 1-hr seminars. Attendance is absolutely essential; there will be attendance sheets for you to sign. The course material is not entirely covered in the readings and will often go beyond them. In addition, I use a lot of slides and examples in lectures to illustrate the material in order to provide you with a deeper understanding of the week`s topic. If you have any obligations that prevent you from regular class attendance, then this course is not for you. In preparation for each class, you are expected to complete the assigned readings and take notes. If you miss any class(es), it is YOUR responsibility to get an update or notes from a fellow classmate, as well as any class announcements. Please do not email me asking for lecture notes for a class you missed. To enhance your learning experience, I will post handouts of the lecture slides on Blackboard every Sunday; these handouts will help you stay organized with your notes and the lecture material. I will NOT be posting all lecture slides, as some of them are quite image-heavy. The seminar questions listed in the schedule are a useful frame for discussion as well as to ensure you grasp the fundamental themes and issues of the week. Ryerson Student Email All students in full and part-time graduate and undergraduate degree programs and all continuing education students are required to activate and maintain their Ryerson online identity at www.ryerson.ca/accounts in order to regularly access Ryerson’s Email (Rmail). Email sent by any other provider will NOT BE OPENED. 2 Evaluation 1. Seminar Participation (20%) Seminars are an integral part of the course, and are thus mandatory. You are expected to demonstrate an ability to critique the information presented in class as well as in the readings by asking questions, answering questions, or commenting in an appropriate and informed way, during the discussion sessions. If you are a shy person, or did not get a chance to speak in class, you also have the opportunity to post questions or comments on the Blackboard discussion forum. You mark will be assessed on the quality of your contributions: coming to class having done the readings, thought about the seminar questions listed in the schedule, and prepared with your own questions or responses to the readings. Simply signing the attendance sheet will only guarantee you partial marks. 2. Midterm (10%) Monday October 22 A short midterm to assess your progress in the course. Midterm will take place in seminar sessions and will cover everything from Week 1-6. Format: 50minutes, short answers and one essay-style question. **Note: The Section 1 lecture for Monday October 22 will be split into the seminar; midterm will take place in the second half of the lecture. 3. Essay Proposal (5%) Monday September 24 This assignment is meant to help you formulate your essay and is designed to get you thinking about your essay early on and receive constructive feedback before you begin writing. In a one-page statement list: a proposed topic, a possible thesis statement and 2-3 sentences outlining an argument, and at least 3 secondary sources and 1 primary source you plan to consult. You may choose to write on any topic that falls within the themes and time periods of this course. Choose one that interests you: explore the “Further Readings” listed on the Course Readings below, Google some of the themes listed, or come talk to me if you’re unsure. 4. Essay Draft (10%) Due Monday November 12 The purpose of this assignment is to make sure you are progressing well from your proposal to the final essay. Your draft needs to be a minimum of 500 words and demonstrate that you have thought about how your argument will support your thesis, and what kinds of evidence you will use. Your introduction should be clearly written with an identifiable thesis, and you should have a solid outline of your supporting arguments as well as any quotations you plan to use. A bibliography list should also be supplied. If you are not well-acquainted with the process of writing history essays, come see me or send me an email before submitting this assignment. 5. Essay (30%) Due Monday December 3 Your final essay should be about 8-10 pages double-spaced and contain a minimum of 5 sources, at least one which must be a primary source. It should expand from your draft (and my comments), include a clear introduction and thesis, a main body of argument & evidence, and a conclusion. Use footnotes as citations, and when quoting directly from other works and/or paraphrasing material, you MUST reference it. See the “Academic Integrity” and “Plagiarism” sections below. 6. Final Exam (25%) TBA The material you will be tested on is cumulative, since the beginning of the term, as covered in lectures, readings, and discussion periods. Format will include: image identification, short answer questions, one or two lengthy essay-style question. We will do a review on Monday December 3. Readings Every class will require a moderate amount of reading; the readings are intended to provide you material for thought and discussion for the seminars, and to be used as a guide for the lectures. All readings will be posted on Blackboard or linked to appropriate websites. In addition, there will be links to websites for you to engage 3 with various primary sources (text, image, object, etc). It is your responsibility to access the readings from Blackboard and online. Missed Term Work or Examinations You are expected to complete all assignments and exams within the time frames and by the dates indicated in this outline. Extensions for the essay or make-ups for the final will only be permitted for a medical or a personal emergency or due to religious observance (request must be received within the first two weeks of the course). I must be notified by email prior to the due date or essay/exam, or as soon as possible after the date, and the appropriate documentation must be submitted. Late assignments will be penalized at 5% of the total grade per day and no assignment will be accepted more than a week after the deadline. For absence on medical or religious observance grounds, official forms may be downloaded from the Ryerson website at www.ryerson.ca/undergraduate/currentstudents/forms. Academic Integrity Ryerson University as a community of scholarship, teaching, and learning, takes academic integrity very seriously. Honesty and integrity are at the core of any educational endeavour. It is our responsibility as individuals, as faculty and students working together in this course, and as members of the Ryerson University community to commit ourselves to honest, ethical behaviour in our academic work and to encourage others to do likewise. You must read the Student Code of Academic Conduct so you are familiar with Ryerson’s policies and procedures: http://www.ryerson.ca/academicintegrity/ Plagiarism The Ryerson Student Code of Academic Conduct defines plagiarism and the sanctions against students who plagiarize: Plagiarism is not an issue for many people, but everyone should know the official policy: plagiarism is a serious academic offence and Ryerson treats it as such. Any degree of intellectual theft or ‘borrowing’ without acknowledgement will not be tolerated in this class. Plagiarism has serious consequences for your grades and careers so don ’t do it! Please familiarize yourself with Ryerson’s code of academic integrity: http://www.ryerson.ca/studentguide/AcademicMatters35.html Please do not, in any shape or form, commit the act of plagiarism. If you are having ANY difficulties with the course material, or with essay writing, or even with reading and understanding, please email me or make an appointment to see me. Course Repeats Senate GPA Policy prevents students from taking a course more than three times. For complete GPA Policy see policy No. 46 at www.ryerson.ca/senate/policies Ryerson Academic Policies For more information on Ryerson’s academic policies, visit the Senate website at www.ryerson.ca/senate Grading Breakdown The following is an explanation of the grading scheme adopted by the History Department. Example: A+ /A /AAn outstanding performance. A student must demonstrate a full knowledge and understanding of the subject matter, show a good ability to analyze and to criticize the analyses of others, organize material well and explain issues clearly, be able to discuss issues in their broader context, and demonstrate some originality. 4 Course Outline Lecture Topics Seminar Themes Week 1 History of Medicine: An Ancient Tradition -no seminar- Week 2 Roots of the Western Medical Tradition Hippocrates & Humoral theory Week 3 The Roman World Alexandrian Anatomy & Galen the Philosopher Week 4 Christianity and the Translation of Texts Religion and medicine Week 5 The Arab-Islamic World Smallpox & measles Week 6 Disease and Society The Decameron: responses to the plague Week 7 Hospitals, Universities & Learned Medicine **MIDTERM** Week 8 Surgeons and their Tools Hands-on knowledge & authority Week 9 Medicinal Magic Astrology as authoritative medicine Week 10 Women’s Bodies & Women’s Secrets The Trotula: a sourcebook of female knowledge Week 11 Promising a Cure Medically promicious patients Week 12 The Renaissance Theatre Vesalius the Galensit? Week 13 Review for final Review for final Week 1. History of Medicine: An Ancient Tradition · introduction · concepts of health and disease · social history of medicine · cultural history of the body · prehistory · Lecture: Section 1, Tuesday September 4 │ Section 2, Wednesday September 5 Further Readings W.F. Bynum and R. Porter, Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine (London & New York: 1993). L. Conard et al, The Western Medical Tradition; 800 BC to AD 1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. M. Lindemann, Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999). R. Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997). 5 C.E. Rosenberg and J. Golden (eds.), Framing Disease: Studies in Cultural History (Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992). Week 2. Roots of the Western Medical Tradition: Ancient Greece · Hippocrates (460-c.377 BC) · Aristotle (384-322 BC) · patient-oriented medicine · Four humours & Four elements · Lecture: Section 1, Monday September 10 │ Section 2, Wednesday September 12 Lecture Readings: Vivien Nutton, “Medicine in the Greek World, 800-50 BC,” in The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800. Eds. L. Conard et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp.11-38. Vivien Nutton, “Hippocrates, The Hippocratic Corpus and the Defining of Medicine,” in Ancient Medicine (New York & London: Routledge, 2004), pp.53-71. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday September 11│ Section 2, Monday September 10 Seminar Readings: Hippocrates, “The Oath” (400 BC) http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/hippooath.html Hippocrates, On Regimen in Acute Diseases (400 BC), Part 1-3 http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/acutedis.html Seminar Questions: 1. Why do you think the humoral theory had such a strong explanatory power? Why is balance such an important concept? 2. What exactly does “regimen” mean? Why do you think it’s important for the physician? 3. What are some prominent features of the Oath? Why do you think this is so? Further Readings D.W. Amuddsen, Medicine, Society and Faith in the Ancient and Medieval World (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1996). H. King, Hippocrates’ Woman: Reading the Female Body in Ancient Greece (London: Rougledge, 1998). S. Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine (New York: Zone Books, 1999). J. Longrigg, “Presocratic Philosophy and Hippocratic Medicine,” History of Science 27 (1989): 1-38. J. Longrigg, Greek Medicine: From the Heroic to the Hellinistic Age (London: Duckworth, 1998). J. Longrigg, Greek Rational Medicine: Philosophy and Medicine from Alcemeon to the Alexandrians (London: Routledge, 1993). V. Nutton, Ancient Medicine (London & New York: Routledge, 2004). V. Nutton, “Humoralism,” W.F. Bynum & R. Porter (eds.), Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine Vol.1 (New York & London, 1993), 281-291. 6 V. Nutton, “Healers in a Medical Market Place: Towards a Social History of Greco-Roman Medicine,” in A. Wear (ed.), Medicine in Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 15-58. W.D. Smith, The Hippocratic Tradition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979). O. Temkin, Hippocrates in a World of Pagans and Christians (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1991). Week 3. Medicine in the Roman World · Hellenistic medicine · Galen (129-216?) · anatomy · medical sects · Alexandrian autopsy and dissection · Lecture: Section 1, Monday September 17 │ Section 2, Wednesday September 19 Lecture Readings: Vivien Nuton, “Roman Medicine, 250 BC-200 AD,” in The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800. Eds. L. Conard et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp.39-70. Vivien Nutton, “Galenic Medicine,” in Ancient Medicine (New York & London: Routledge, 2004), pp.230-247. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday September 18│ Section 2, Monday September 17 Seminar Readings: Galen, “The Best Doctor is also a Philosopher,” in Galen, Selected Works, tr. P.N. Singer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), pp.30-34. Seminar Questions: 1. According to Galen, why is the best physician also a philosopher? 2. What similar or different features do you observe between Greek and Roman medicine? 3. Does Galen’s physiological system of the body fit with the ideals of humoral medicine? Why or why not? Further Readings: R. Flemming, Medicine and the Making of Roman Women: Gender, Nature, and Authority from Celsus to Galen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). R. Jackson, Doctors and Diseases in the Roman Empire (London: British Museum, 1988). H.King, Greek and Roman Medicine (Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 2001). J. Longrigg, “Anatomy in Alexandria in the Third Century BC,” British Journal for the History of Science 21 (1988): 455-488. V. Nutton, “From Galen to Alexander, aspects of medicine and medical practice in late antiquity,” in J. Scarborough, ed., Symposium on Byzantine Medicine (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1985), 1-14. V. Nutton, “Galen at the Bedside: The methods of a medical detective,” in W.F. Byum and Roy Porter (eds), Medicine and the Five Senses (Cambridge: Cambridge University Pres, 1993), 1-6. 7 V. Nutton, “Healers in the Medical Market Place: Towards a Social History of Graeco-Roman Medicine,” in A. Wear (ed.), Medicine in Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 15-58. P. Potter, “Herophilus of Chalcedon: An Assessment of his place in the History of Anatomy,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 50 (1976): 45-60. O. Temkin, Galenism: The Rise and Decline of a Medical Philosophy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1973). H. Von Staden, “Anatomy as Rhetoric: Galen on Dissection and Persuasion,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 50.1 (1995): 47-66. H. Von Staden, Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989). Week 4. Christianity and the Translation of Texts **Essay Proposal Due** · Hellenistic medicine · monastic scribes · Galenism · encyclopaedias · the Venerable Bede (c.672-735) · practical medicine · Lecture: Section 1, Monday September 24 │ Section 2, Wednesday September 26 Lecture Readings: Vivien Nutton, “Medicine in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages,” in The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800. Eds. L. Conard et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp.71-89. Gary B. Ferngren, “Early Christianity as a Religion of Healing,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 66 (1992): 1-15. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday September 25│ Section 2, Monday September 24 Seminar Readings: Medieval Manuscripts at Thomas Fisher Library (University of Toronto): http://link.library.utoronto.ca/vellum/ Browse through UCLA’s Index of Medieval Medical Images: http://digital.library.ucla.edu/immi/ Seminar Questions: 1. What exactly is the Christian practice of healing? 2. What strengths and/or weakness can you gather from the scriptorium practices? 3. What observations can you make from the medieval manuscripts? What do you think they signify? Further Readings D.W. Amuddsen, Medicine, Society and Faith in the Ancient and Medieval World (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1996). D.W. Amundsen, “Medicine and Faith in Early Christianity,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 56 (1982): 356-50. B. Bowers, The Medieval Hospital and Medical Practice (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007). M.L. Cameron, Anglo-Saxon Medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). W. Eamon, Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996). 8 F. Getz, Medicine in the English Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998). B. Harvey, Living and Dying in England, 1100-1540: The Monastic Experience (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995). A. Montford, Health, Sickness, Medicine and the Friars in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004). F.S. Paxton, “Curing Bodies, Curing Souls: Hrabanus Maurus, Medical Education, and the Clergy in Ninth-Century Francia,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 50 (1995): 230-252. C. Rawcliffe, Medicine & Society in Later Medieval England (Sutton, 1995). N. Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine (Chicago, 1990). O. Tempkin, Hippocrates in a World of Pagans and Christians (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1991). L.E. Voigts, “Anglo-Saxon Plant Remedies and the Anglo-Saxons,” Isis 70 (1979): 250-286. Week 5. The Arab-Islamic World **Oct 8-12 Fall Break** · assimilation of humoural medicine · Avicenna (1126-98) · Islamic medicine · Arabic medicine · al-Razi · patrons & patronage Lecture: Section 1, Monday October 1 │ Section 2, Wednesday October 3 Lecture Readings: Lawrence Conard, “The Arab-Islamic Tradition,” in The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800. Eds. L. Conard et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp.93-138. E. Savage-Smith, “Attitudes Towards Dissection in Medieval Islam,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 50:1 (1995): 67-110. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday October 2│ Section 2, Monday October 1 Seminar Readings Avicenna, Canon. Book 1, Fen 1. In E. Grant, ed. A Source Book in Medieval Science (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1974). Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya’ al-Razi (Latinized as Rhazes or Rhases), A Treatise on the Smallpox and Measles, ed. and trans. by W.A. Greenhill (London, the Sydenham Society, 1848), 27-31. Available on Google Books: http://books.google.ca/books?id=0XISAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage& q&f=false Seminar Questions: 1. Why is al-Razi referred as the “Galen of the Arabs?” What implications can such a title have? 2. Is religion and/or magic dominant in the Arab-Islamic tradition? How? Why? 3. What key features can you observe from al-Razi’s treatise? Further Readings: 9 C. Alvarez-Millán, “Graeco-Roman Case Histories and their Influence on Medieval Islamic Clinical Accounts,” Social History of Medicine 12 (1999): 19-33. L. Chipman, The World of Pharmacy and Pharmacists in Mamlūk Cairo (Leiden, 2009). M.D. Dols, “The Leper in Medieval Islamic Society,” Speculum 58 (1983): 891-916. M.D. Dols, “The Origins of the Islamic Hospital: Myth and Reality,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 61 (1987): 367-390. D. Jacquart, “The Influence of Arabic Medicine in the Medieval West,” in R. Rashed, Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science vol. 3 (London, 1996), 963-984. G. Leiser, “Medical Education in Islamic Lands from the Seventh to the Fourteenth Century,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 38 (1983): 48-75. M.S. Mossensohn, Ottoman Medicine: Health and Medical Institutions, 1500-1700 (New York, 2009). P.E. Pormann, “The Physician and the Other: Images of the Charlatan in Medieval Islam,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 79 (2005): 189-227. P.E. Pormann and E. Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2006). E. Savage-Smith, “Islamic Culture and the Medical Arts” at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/islamic_medical/islamic_00.html Week 6. Disease and Society · Black Death · community · legislation · mortality · God-sent punishment · public-health measures · social responses · Lecture: Section 1, Monday October 15 │ Section 2, Wednesday October 17 Lecture Readings: Katherine Park, “The Black Death,” in Kenneth F. Kiple (ed.), The Cambridge World History of Human Disease (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp.612-616. J. Arrizabalaga, “Facing the Black Death: Perceptions and Reactions of University Medical Practitioners,” in L. GarciaBalleser, R. French, and J. Arrizabalga (eds.), Practical Medicine from Salerno to the Black Death (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp.237-288. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday October 16│ Section 2, Monday October 15 Seminar Readings: “The Report of the Paris Medical Faculty, October 1348” in R. Horrox. The Black Death (Vancouver: Manchester University Press, 1994), pp.158-163. G. Boccaccio, “Introduction to the Decameron (c. 1350),” Boccaccio, The Decameron. trans. M. Rigg, (London: David Campbell, 1921), Vol. 1, 5-11. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/boccacio2.html) 10 “Petararch on the Death of his Friends,” in R. Horrox (ed.), The Black Death (Vancouver: Manchester University Press, 1994), pp.248-249. Seminar Questions: 1. In what ways does Boccaccio capture the experiences of plague-stricken cities? 2. What guidelines did the Paris Medical Faculty recommend for dealing with plague? What explanations for these guidelines did they offer? 3. How did Christians see the relationship between plague and sin? Why? Further Readings: D.W. Amudsen, Medicine, Society, and Faith in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1996). J. Arrizabalga, J. Henderson, and R. French, The Great Pox: The French Disease in Renaissance Europe (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1997). A.G. Carmichael, Plague and the Poor in Renaissance Florence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986). M. Dols, “The comparative Communal Responses to the Black Death in Muslim and Christian Societies,” Viator 5 (1975): 269-287. F.M. Getz, “Black Death and the Silver Lining: Meaning, Continuity, and Revolutionary Changes in Histories of Medieval Plague,” Journal of the History of Biology 24 (1991): 265-289. C. Jones, “Plague and its Metaphors in Early Modern France,” Representations 53 (1996): 97-127. R. Palmer, “The Church, Leprosy and Plague in Medieval and Early Modern Europe,” Studies in Church History 19 (1982): 79-99. K. Siena (ed.), Sins of the Flesh: Responding to Sexual Disease in Early Modern Europe (Toronto: Center of Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2005). Week 7. Hospitals, Universities, and Learned Medicine *Midterm* Monday lecture: 1hr lecture, 1hour midterm Wednesday lecture: 1hr lecture, 1hour seminar · teaching methods · institutional history · print and books · Canon as textbook · medical curriculum · leper hospitals Lecture: Section 1, Monday October 22│ Section 2, Wednesday October 24 Lecture Readings: Nancy G. Siraisi, “Medical Education,” in Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), pp.48-65. Martha Karlin, “Medieval English Hospitals,” in Lindsay Granshaw & Roy Porter (eds.), The Hospital in History (London: Routledge, 1988), pp.21-40. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday October 23│ Section 2, Monday October 22 11 Seminar Readings: N/A Seminar Questions: 1. Did the hospital emphasize the Christian duty of charity? How did it, if at all, conflict with the role of the physician? 2. How did the Articella mark a turning point in the revival of medicine in the West and what role did it play in university curriculum? 3. What observations can you make in the University of Bologna’s Regulations for Conducting a Dissection? Further Readings: K. Park and J. Henderson, “The First Hospital Among Christians: The Ospedale di Santa Maria Nuova in Early Sixteenth Century Florence,” Medical History 35:2 (1991): 164-188. B. Bowers, The Medieval Hospital and Medical Practice (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007). S. Cavallo, Charity and Power in Early Modern Italy: Benefactors and their Motives in Turin, 1541-1789 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995). B. Harvey, Living and Dying in England, 1100-1540: The Monastic Experience (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995). J. Henderson, The Renaissance Hospital: Healing the Body and Healing the Soul (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006). N. Siraisi, Avicenna in Renaissance Italy: The Canon and Medical Teaching in Italian Universities after 1500 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981). K. Park, “Healing the Poor: Hospitals and Medical Assistance in Renaissance Florence,” in J. Barry and C. Jones (eds.), Medicine and Charity Before the Welfare State (London: Routledge, 1991), 26-45. M. Rubin, “Imagining Medieval Hospitals: Considerations on the Cultural Meaning of Institutional Change,” in J. Barry and C. Jones (eds.), Medicine and Charity Before the Welfare State (London: Routledge, 1991), 14-25. L. Granshaw and R. Porter (eds.), The Hospital in History (London: Routledge, 1988). O’Boyle, The Art of Medicine: Medical Teaching at the University of Paris, 1250-1400 (Leiden; Brill Publications, 1998). Week 8. Surgeons and their Tools · barber-surgeons · instrumentation · history of objects · guilds · wounds debate · Henri Mondeville · Guy de Chauliac Lecture: Section 1, Monday October 29│ Section 2, Wednesday October 31 Lecture Readings: Nancy G. Siraisi, “Surgeons and Surgery,” in Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), pp.153-186. 12 Margaret Pelling, “Appearance and Reality: Barber-Surgeons, the Body, and Disease,” in A.L. Beier and R. Finaly (eds.), London 1500-1700: The Making of the Metropolis (New York: Longman, 1986), 82-112. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday October 30│ Section 2, Monday October 29 Seminar Readings: Guy de Chauliac, “History of Surgery,” in E. Grant, ed. A Source Book in Medieval Science (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1974), 791-795. Henry of Mondeville, “The Treatment of Wounds,” in E. Grant, ed. A Source Book in Medieval Science (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1974), 803-806. Guy de Chauliac, “The Treatment of Wounds,” in E. Grant, ed. A Source Book in Medieval Science (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1974), 806-807. Seminar Questions: 1. Why did Guy de Chauliac reject Henri de Mondeville’s method of wound treatment? 2. How important were surgical instruments for asserting the surgeon’s hands-on knowledge and authority? 3. What assessments can you make about the patients that encountered these procedures at the barbershop? Further Readings: Tony Hunt, The Medieval Surgery (Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 1992). G. Lawrence, “Surgery Traditional,” in W.F. Bynum and R. Porter (eds.), Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine vol.2 (London & New York: Routledge, 1993), 961-983. G. Manjo, The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1975). M.C. Pouchelle, The Body and Surgery in the Middle Ages, trans. Rosemary Morris (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990). M.S. Spink and G.L. Lewis, Albucasis on Surgery and Instruments (London: The Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine, 1973). L. Toledo-Pereyra, “Galen’s contribution to surgery” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 28 (1973): 357-75. O.H. Wangensteen & S.D. Wangensteen, The Rise of Surgery: From Empiric Craft to Scientific Discipline (Minneapolis/Folkstone, 1978). M. McVaugh, “Surgical Education in the Middle Ages,” Dynamis 20 (2000): 283-304. M. McVaugh, “Royal Surgeons and the Value of Medical Learning: the Crown of Aragon, 1300-1350,” in L. GraciaBallester, R. French, et al (eds.), Practical Medicine from Salerno to the Black Death (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994). Week 9. Medicinal Magic · occult medicine · astrology · religious healers · miracles · the sickbed · alchemy 13 Lecture: Section 1, Monday November 5│ Section 2, Wednesday November 7 Lecture Readings: Katherine Park, “Magic and Medicine: The Healing Arts,” in Judith C. Brown and Robert C. Davis (eds.), Gender and Society in Renaissance Italy, London: Addison Wesley Longman, 1998. Roger French, “Astrology in Medical Practice,” in L. Garcia-Ballester, R. French, and J. Arrizabalaga (eds.), Practical Medicine from Salerno to the Black Death (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 30-59. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday November 6│ Section 2, Monday November 5 Seminar Readings: Anniina Jokien, “Zodiac Man; Man as Microcosm,” Luminarium 1 Oct 2011 [Accessed August 2012] http://www.luminarium.org/encyclopedia/zodiacman.htm Seminar Questions: 1. Why was an understanding of astrology fundamentally important to a physician’s practice? 2. Can you derive any connections from the Zodiac Man and the humoural theory? 3. Discuss why herbal-based remedies were popular as (self-) treatments. Further Readings: D.W. Amuddsen, Medicine, Society and Faith in the Ancient and Medieval World (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1996). A.G. Debus, The French Paracelsians: The Chemical Challenge to Medical and Scientific Tradition in Early Modern France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991). A. Grafton and N. Siraisi, “Between the Election and my Hopes: Girolamo Cardano and Medical Astrology,” in W. Newman and A. Grafton (eds.), Secrets of Nature: Astrology and Alchemy in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 2001), 69-131. John Harley, “Historians as Demonologists: The Myth of the Midwife-Witch,” Social History of Medicine 3 (1990): 1-26. L. Kassell, Medicine and Magic in Elizabethan. Simon Forman: Astrologer, Alchemist, and Physician (Oxford: Claredon Press, 2005). S. Page, Astrology in Medieval Manuscripts (Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2002). R. Palmer, “Medical Botany in Northern Italy in the Renaissance,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 78 (1985): 149-157. N. Siraisi, “The Medicine of Dreams,” in The Clock and the Mirror: Girolamo Cardano and Renaissance Medicine (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 174-191. N.G. Siraisi, “The Hidden and the Marvelous,” in The Clock and the Mirror: Girolamo Cardano and Renaissance Medicine (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 149-173. 14 Week 10. Women’s Bodies & Women’s Secrets **Drop Deadline Nov. 16** **Essay Draft Due** · gender · sex · childbirth · anatomy illustrations · midwifery · physician’s role· religious doctrine · household practice · Lecture: Section 1, Monday November 12│ Section 2, Wednesday November 14 Lecture Readings: M. Cabré, “Women or Healers? Household Practices and the Categories of Health Care in Late Medieval Iberia,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 82.1 (2008), pp.18-51. Katherine Park, “Secrets of Women,” in Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and Origins of Human Dissection (New York: Zone Books, 2006), pp.77-120. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday November 13│ Section 2, Monday November 12 Seminar Readings: M. H. Green (ed.), The Trotula: a Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), pp. 92-115 and selected pages from the Introduction. Public record of the labour of Isabel de la Cavalleria, January 10, 1490, Zaragoza, trans. Montserrat Cabré. http://www.the-orb.net/birthrecord.html Seminar Questions: 1. Who is Trotula? What do the texts attributed to Trotula reveal about women’s health and women’s bodies? 2. How do the woodcuts of Jacobo Berengario reveal the transformation of the dissected female body from an authoritative possessor of secrets to self-display for direct anatomical study? 3. Why is the household important for maintaining health? Further Readings: J. Cadden, The Meanings of Sex Differences in the Middle Ages: Medicine, Natural Philosophy, and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995). M. Fissell, “Gender and Generation: Representing Reproduction in Early Modern England,” Gender and History 7:3 (1995): 433-456. R. Flemming, Medicine and the Making of Roman Women: Gender, Nature, and Authority from Celsus to Galen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). M.H. Green, “Women’s Medical Practice and Health Care in Medieval Europe,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture 14 (1989): 434-473. M.H. Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynecology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). H. King, Hippocrates’ Woman: Reading the Female Body in Ancient Greece (London: Rougledge, 1998). D. Jacquart and C. Thomasset, Sexuality and Medicine in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985). 15 H. Marland (ed.), The Art of Midwifery: Early Modern Midwives in Europe (London; Routledge, 1993). Riddle, Jones M. and Estes, J. Worth, “Oral Contraceptives in Ancient and Medieval Times,” American Scientist 80 (1992):226-33. Week 11. Promising a Cure · medical pluralism · quackery · medical marketplace · patient’s choices · contracts for cures · surgeons & apothecaries · Lecture: Section 1, Monday November 19│ Section 2, Wednesday November 21 Lecture Readings: David Gentlicore, “Medical Pluralism in the Kingdom of Naples,” in Healers and Healing in Early Modern Italy (Oxford: Manchester University Press, 1998), pp.1-28. David Gentilcore, “Charlatans, Mountebanks, and other Similar People: The Regulation and Role of itinerant Practitioners in Early Modern Italy,” Social History 20 (1995): 291-231. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday November 20│ Section 2, Monday November 19 Seminar Readings: Go to Wellcome Images http://images.wellcome.ac.uk/ and search images of “quacks” or “charlatans” (be sure you select “Historical images” under the search setting) Seminar Questions: 1. What is meant by a patient being “medically promiscuous?” 2. What observations can you make from the images of the quack or charlatan? 3. Do you think Gentlicore’s model of medical pluralism is effective in capturing the diversity of practitioners and practices? Why or why not? Further Readings: W. Eamon, Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996). D. Gentilcore, Healers and Healing in Early Modern Italy (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998). D. Gentilcore, From Bishop to Witch: The System of the Sacred in Early Modern Terra d’Otarnto (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992). D. Gentilcore, Medical Charlatanism in Early Modern Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006). L. Roper, Oedipus and the Devil: Witchcraft, Sexuality and Religion in Early Modern Europe (London: Routledge, 1994). K. Park, Doctors and Mediine in Early Renaissance Florence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985). M. Pelling and C. Webster, “Medical Practitioners,” in C. Webster (ed.), Health, Medicine, and Mortality in the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1985), 165-236. 16 G. Pomata, Contracting a Cure: Patients and Healers, and the Law in Early Modern Bologna (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1998). P.E. Pormann, “The Physician and the Other: Images of the Charlatan in Medieval Islam,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 79 (2005): 189-227. Robert Ralley, “Medical Economies in Fifteenth Century England,” in Mark Jenner and Patrick Wallis (eds.), Medicine and the Market in England and its Colonies, c.1450-1850 (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2007), pp.2446. V. Nutton, “Healers in a Medical Market Place: Towards a Social History of Greco-Roman Medicine,” in A. Wear (ed.), Medicine in Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 15-58. Week 12. The Renaissance Theatre · dissection· Renaissance humanism · practical medicine · Vesalius · folios · illustrations and woodcuts · Lecture: Section 1, Monday November 26│ Section 2, Wednesday November 28 Lecture Readings: Andrea Carlino, “Representing the Body: The Visual Culture of Renaissance Anatomy” in Paper Bodies: A Catalogue of Anatomical Fugitive Sheets (London: Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 1999), pp.1-45. Nancy G. Siraisi, “Vesalius and the reading of Galen's teleology,” Renaissance Quarterly, 1997, vol. 50, pp. 1-37. Seminar: Section 1, Tuesday November 27│ Section 2, Monday November 26 Seminar Readings: Andreas Vesalius, “To the Divine Charles V,” “Preface,” and “Instructions to the Printer,” and various woodcuts in de Humani corporis fabrica (1543). http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/vesalius_home.html Seminar Questions: 1. Do you consider Vesalius to be a “true Galenist?” Why or why not? 2. What features do you notice in Vesalius’ instructions to his printer? Why do you think these instructions were important? 3. How have representations of the body transformed in Renaissance medicine? How do the representations differ from medieval accounts of the body? Further Readings: A. Carlino, Books of the Body: Anatomical Ritual and Renaissance Learning (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). A. Cunningham, The Anatomical Renaissance: The Resurrection of the Anatomical Projects of the Ancients (Aldershot: Scholar Press, 1997). G. Ferrari, “Public Anatomy Lessons and the Carnival: The Anatomy Theatre of Bologna,” Past and Present 117 (1987): 50-106. R. French, Dissection and Vivisection in the European Renaissance (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999). 17 M. Kemp, “The Mark of Truth; Looking and Learning in Some Anatomical Illustrations from the Renaissance and the Eighteenth Century,’ in W. Bynum and R. Porter (eds.), Medicine and the Five Senses (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 85-121. K. Park, “The Life of the Corpse: Division and Dissection in Late Medieval Europe,” Journal of the History of Medicine 50 (1995): 111-132. K. Park, “The Criminal and the Saintly Body: Autopsy and Dissection in Renaissance Italy,” Renaissance Quarterly 47 (1994): 1-33. K.M. Reeds, “Renaissance Humanism and Botany,” Annals of Science 33:6 (1976): 519-542. N. Siraisi, Avicenna in Renaissance Italy: The Canon and Medical Teaching in Italian Universities after 1500 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981). N. G. Siraisi, “The Uses of Anatomy,” in The Clock and the Mirror: Girolamo Cardano and Renaissance Medicine (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 93-118. 18