Handout #7 - Department of Agricultural Economics

advertisement

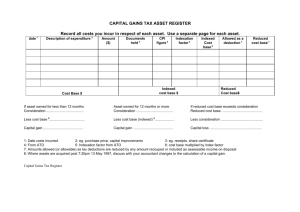

Handout #7 Agricultural Economics 489/689 Topic #7 Spring Semester 2008 John B. Penson, Jr. 1 A. Other Capital Budgeting Applications There are a number of other applications of the time value of money and capital budgeting. The section focuses on two such applications: (1) the optimal age to replace machinery and equipment and (2) the relative merits of purchasing machinery and equipment with a new loan versus acquiring these assets with a capital lease. Asset replacement decision The decision to replace an aging major piece of equipment in the firm’s production operations also represents an application of capital budgeting. The decision to replace a machine is somewhat different from the decision to expand because the cash flows from the old machine must also be considered. Let’s examine the example above where a firm is considering replacing an 2 old machine with a new one costing $12,000. The price received from the sale of the old machine which has a salvage value of zero is $1,000. The salvage value of the new machine at the end of year 5 is $2,000 which is subject to depreciation recapture. Let’s further assume the firm is in the 40 percent income tax bracket. Line 6 reflects the decrease in operating costs if the replacement is made due to increased efficiency ($3,000) less the associated increase in taxes associated with this economic gain ($1,200 or .40 x $3,000). Assuming a discount rate of 12 percent resulting in the present value interest factors on line 17, we see the net present value of the replacement project would be -$522. Thus, we would reject the decision to replace the machine at the present time and continue to use the old machine in the firm’s production operations. The payback period of the project based on the net operating cash flows on line 11would be 4.1 years, reflecting that it would take almost the entire period to recover the total net investment of $11,400 shown on line 5. Optimal replacement age. A different twist on asset replacement decisions is the determination of the optimal age to replace machinery and equipment. This involves finding the year in the service life of an asset prior to the year where the marginal costs associated with its current use becomes greater than the cost of replacing the asset. The year in which the present value of a stream of future ownership costs is minimized represents the optimal age to replace an aging depreciable asset. Lease vs. buy The decision to finance the purchase of an asset or finance the use of an asset for a specific number of years involve determining which of these two alternatives results in the least cost to the firm. This is done by comparing the present value of the net outflow of funds over the life of the two alternatives. The net advantage to leasing calculation is as follows: Less: Installed cost of the asset Investment tax credit retained by the lessor (company providing asset) 3 Less: Less: Plus: Less: Equals: Present value of the after-tax lease payments Present value of the depreciation tax shield Present value of after-tax operating costs incurred if owned but not if leased Present value of the after-tax salvage value Net advantage to leasing (NAL) The installed cost of the asset equals the purchase price plus installation and shipping charges. This forms the basis upon which depreciation and investment tax credit (if allowed) are computed. The present value of the after-tax lease payments reduces the NAL. These payments are discounted at the firm’s after-tax cost of borrowing rather than the firm’s risk adjusted required rate of return to reflect the fact that lease payments are contractually known in advance and thus not subject to uncertainty. The present value of the depreciation tax shield reduces the cost of ownership and hence is subtracted when computing the NAL. Since the annual depreciation amounts are also known with relative certainty, they are also discounted at the firm’s after-tax cost of borrowing. Sometimes there are operating costs incurred if the asset is owned but not if leased. These may include property tax payments, insurance, and some maintenance expenses. If they do exist, they represent a benefit to leasing and thus increase the NAL. Since they too are also known with relative certainty, they are discounted at the firm’s after-tax cost of borrowing. Finally, if the asset is owned, the owner will receive the after-tax salvage value. This is lost of the assets is instead leased. Thus, the after-tax salvage value reduces the NAL. Since this value is not known with relative certainty, it should be discounted by the firm’s after-tax weight cost of capital which includes a risk premium. Let’s consider the following example. Suppose a firm is considering leasing an asset that can be purchased for $50,000, including delivery and installation. Alternatively, the asset can be leased for a six-year period at a beginning of the year lease payment of $10,000. 4 Suppose the firm can borrow the funds to purchase the asset at a rate of 10 percent. If the asset is purchased, it will require insurance and a maintenance contract costing $750 annually. The asset would me depreciated as a fiveyear asset where the allowable annual rates are 15%, 22%, 21%, 21% and 21%. Assume an investment tax credit rate of 10% exists. The calculation of the net advantage to leasing in this case example would be as follows: where: 5 This case example suggests that the net advantage to leasing is negative, which means the firm would be better off economically if it borrowed and purchased the asset rather than leasing it. This general procedure can be used to evaluate any lease versus buy decision once it has been determined using standard capital budgeting techniques (i.e., net present value) that an asset should be acquired. 6 7