Business Methods Patents and Firm Value:

advertisement

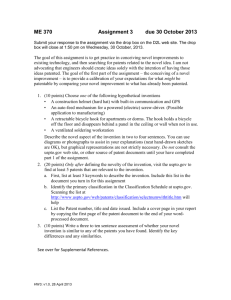

Business Methods Patents and Firm Value: An Events Study (Preliminary Draft; Do Not Quote.) Todd Palmer Associate Professor of Management Sciences St. Bonaventure University St. Bonaventure, NY 14778 716-375-4037 tpalmer@sbu.edu Terrence Moran Instructor of Management Sciences St. Bonaventure University St. Bonaventure, NY 1 Business Method Patents and Firm Value: An Events Study Recent research has suggested that non-financial indicators such as patent approvals can aid the financial analyst in assessing a company’s value. In State Street Bank & Trust Company v. Signature Financial Group, the Federal Court of Appeals found that business methods were patentable, opening the floodgates for the issuance of these types of patents in the years since. Utilizing an eventstudy methodology we found abnormal market returns on days –16, -15, and –1 (with 0 being the event day of issuance and publication of the patent). These days corresponded with days that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) releases information concerning issuance to the potential patent holders or in the case of day –1, no further practical action can be taken by the USPTO to withdraw patent approval. This research suggests that innovative business processes may be linked to value creation. 2 I. Introduction In July of 1998 the D.C. Circuit Federal Court of Appeals dramatically challenged the traditional notion of what constitutes a patentable idea. In State Street Bank & Trust Company v. Signature Financial Group, the court permitted the patenting of a business process manifested as a unique software program, overturning a lower court’s conclusion that business methods were merely abstract ideas and as such could not receive patent protection.1 The decision opened the door for other companies to apply for similar “business methods” patents to protect their own financial and data processing innovations. Since that ruling, patents have been granted to, among others: British Telecom for “hyperlinks” technology (McIntosh, 2000); Principals at New Frontier Advisors LLC for a portfolio optimization program (Kovaleski, 2000); Lincoln National Risk Management, Inc. for automated insurance underwriting software (Reich-Hale, 2000). Kernel Creations Ltd. for a technology for preparing a patent application (Chartrand, 2000). The decision and ensuing flurry of business method patent applications 2 have resulted in a heated controversy among industry leaders, government regulators 1 Signature Financial Group developed a process and software for managing mutual funds that pooled certain expenses in account management thus permitting certain federal tax benefits. Signature obtained a patent that was challenged by State Street Bank, a competitor. The court, in holding for Signature, effectively dismissed two rationales that were previously recognized grounds for invalidating patents: that patents that were essentially mathematical algorithms were not patentable and that methods for doing business were not patentable. See Updike (1998). 2 OHaver and Rodgers (2000) report that one “large commercial bank” has been granted more than fifty patents for asset management processes and systems, while another “large nonfinancial” company has filed more than 300 business methods patents. 3 and the patent applicants; lawsuits have inevitably followed. AMEX, for example, is suing two entrepreneurs who patented an “open-end mutual fund securitization process”, the same process by which AMEX trades its exchange traded funds (Lucchetti, 2000). Amazon.com is suing Barnesandnoble.com to protect its “one-click” patent and Priceline.com is suing Microsoft to safeguard its reverse auction patent (O’Haver and Rodgers, 2000). A patent is a grant from the government that gives the innovator an exclusive right to produce, use, and sell the innovation for a period of twenty years from the date of filing for the patent. For a patent to be granted the innovation must be genuine, novel, useful, and not obvious in the light of current technology. What is a business method? Neither Congress nor the courts have adequately defined the term. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) classifies business method patents under Class 705 (Data Processing: Financial, Business Practice, Management or Cost/Price Determination) and provides the following definition: This is the generic class for apparatus and corresponding methods for performing data processing operations, in which there is a significant change in the data or for performing calculations operations wherein the apparatus or method is uniquely designed for or utilized in the practice, administration, or management of an enterprise, or in the processing of financial data…. The arrangements in this class are generally used for problems relating to the administration of an organization, commodities or financial transactions (USPTO, 2001). Even a cursory examination of the definition reveals its vague nature. While many of the business patents that have been granted since State Street involve business methods that are intertwined with software, earlier court cases have provided illustrations of business patents that are not 4 software based. Historical examples of these low-tech business methods patents include: a method for parking autos at drive-in theatres in order to maximize visibility (4th Circuit Court of Appeal, 1949) and an accounting method thought to prevent fraud (2nd Circuit Court of Appeals, 1908). Hence, due to the lack of a viable definition, many commentators and businesspeople have espoused the broader view, one that has been adopted in practice by the USPTO that has recently issued a white paper that acknowledging the controversial nature of these patents (USPTO, 2000). Dreyfuss (2001) argues that business method patents are “bad for business” because they reduce the quality of patents awarded, deter competition among existing companies and deter new business start-ups. The purpose of this research is to examine the market response to the granting of these business methods patents providing a unique opportunity to directly estimate the value of business innovations that up until now have remained beyond the reach of traditional valuation methods. The results will add to the growing body of finance literature on “nonfinancial” indicators of firm value. In a survey of financial analysts, Dempsey, Gatti, Grinnell and Cats-Baril (1997) report that the investment community recognizes the value of non-financial operating measures as leading indicators of long-term financial success and are interested in using a broad range of nonfinancial information. That information, however, is not as readily available as traditional financial data, so it is not used as often. In addition, Lev and Zarowin 5 (1999) find the usefulness of financial information like reported earnings, cash flows and book values has declined over the past 20 years. Recent research has suggested that non-financial indicators such as patent approvals can aid the financial analyst in assessing a company’s value. Deng, Lev and Narin (1999) find “patent measures reflecting the volume of companies’ research activity, the impact of companies’ research on subsequent innovations, and the closeness of research and development to science are reliably associated with the future performance of R&D-intensive companies in capital markets”.3 We extend this research by looking specifically at the market reaction to the granting of business method patents. This is of interest to researchers in other business disciplines besides finance, including law, management, human resources, marketing and management information systems. The debate between finance and these areas is whether highly touted marketing, management and data processing innovations truly add value to the business enterprise, as financial theory suggests they should in order to be justified. Research in these fields is only beginning to attempt to make the link between innovative business processes and value creation. We use a traditional event-study methodology to examine the market reaction to the granting of business method patents to publicly traded companies over the past fifteen years. From a financial analyst’s perspective, we are interested in whether business method patent grants are useful indicators of future value. 3 For additional examples of analyses of other types of non-financial indicators, see Ittner and Larcker (1998) and Amir and Lev (1996). 6 We find that cues as provided by the USPTO serve to alert the potential patent holders as to the probable approval of the patent resulting in abnormal returns on days -16, -15, and -1. The largest returns were on days –16 and –15 probably reflecting the issuance of official notification by the USPTO to the potential patent holder. Smaller returns were recorded on day –1, the day prior to publication of the official Patent Gazette and issuance of the patent. II. Data and Methods From a sample of 215 Class 705 patents applications approved by the USPTO in subclass 35 (Finance) and subclass 39 (funds transfer or credit transaction) through December 31, 2000, we identify 88 observations in which the assignee is publicly traded company with data available on the CRSP tapes. In 5 cases in which the assignee has two patent approvals with 20 days of one another, we eliminate the second observation, yielding a final sample of 83 observations. One additional firm was deleted because it had fewer than 50 days of returns in the estimation period. Because some companies had multiple Class 705 approvals during the sample period, the final sample of 82 observations includes 36 different companies (see table 1). Although the event dates range from 1988 to 2000, 73 of 83 occurred in 1998, 1999 or 2000, reflecting the recent rise in popularity of Class 705 filings. The USPTO always releases patent approvals on Tuesday; so all event days are Tuesdays. We use a standard event-study methodology to estimate both marketadjusted and market-model abnormal returns around the event date using the CRSP value-weighted index. We estimate a market model for each firm during a 7 120-day estimation period from day –141 to day –21, and we estimate abnormal returns and cumulative abnormal returns over a 41-day event window from day –20 to +20. For both models we use time series standard deviation method (Brown and Warner, 1985) to generate test statistics and report both the standard t-statistic and a generalized sign test. The null hypothesis for the sign test is that the percentage of positive returns is the same in the event window as the estimation period. See Cowan (1992) for details III. Empirical Results In general, we find a significant market response to the final approval of business method patents on day –1, the Monday prior to the event date, and on days –15 or –16, the Monday and Tuesday three weeks prior to the event date. These results tend to be consistent across estimation models and statistical tests. Market adjusted abnormal returns are reported in Table 2. We find statistically significant average abnormal returns (at the 5% level using the standard t-test) on days –16, -15 and –1, equal to 1.06%, 0.84% and 1.12%, respectively. A number of days have statistically significant returns according to the generalized sign test, including days –15 and –1. The results are similar for market model abnormal returns in Table 3. Days –15 and –1 are significant at the 10% and 5% levels, respectively, according to the parametric t-test. Cumulative abnormal returns for both methods are reported in Tables 4 and 5. None of the cumulative returns over the three intervals [(-20,-2), (-1,0), (+1, +20)] are significant with the market-adjusted model. However, cumulative 8 returns are significantly positive over the interval (-1, 0) and significantly negative over the interval (+1,+20) using the market model. The results in Tables 4 and 5 suggest that the market model may be upward biased in the estimation period, resulting in a negative post-event drift. If the securities in the sample are generating positive abnormal returns during the estimation period, the use of an estimation period prior to such a run-up will result in upward biased alphas in the market model regressions. This leads to downward-biased abnormal returns in the event window, because this abnormal performance is “expected” to continue through the event window. When the downward biased returns are cumulated over the event window, the results show a continued downward drift.4 Evidence from the parameter estimates of the individual firms supports this contention that the pre-event model parameters are biased upward. On average, 46% of the residuals from all the models are greater than 0, and only 17 of the 83 individual models had more than 50% positive residuals. There are a number of ways to avoid this biased benchmark problem. One is to use a post-event estimation period; this is not practical in our case since many of the event dates are in 2000, and post event returns are not available. A second solution is to use a market adjusted model with the CRSP value-weighted index, which avoids the pre- and post-benchmarking problem entirely. We suggest that this is appropriate for our sample, since the average beta parameter from the market models is 1.06 versus the CRSP value-weighted index. 4 See Albert and Smaby (1996) for a discussion of the biased benchmark problem in the context of analyst recommendations. 9 IV. Discussion Our empirical results suggest that something is happening on day –1 and days –15 and –16. Is the market actually responding to new information in the form of business method patent approvals, or are these results an artifact of the data and/or the methodology? We argued in the previous section that the market-adjusted model is a reasonable approach to use to avoid the apparent biased benchmark problem inherent in our sample, so we are confident that we are detecting a market response to these events. But why are days –1, -15 and – 16 important? Conversations with patent attorneys and the press officer of the USPTO suggest possible explanations. Patent approvals can take years from the time of the initial filing to the final approval. However, as time goes on the likelihood that a patent will ultimately be approved increases. Until the patent is actually published in the Patent Gazette, the official publication of the USPTO, it has not been officially issued. Three weeks prior to the issuance of that particular Gazette, the publishing office starts to work on that issue, sending an "issue notification" to the patent holder. On it will be the patent number and the date that it is expected that the patent will be published. This is also the date on which the materials are actually transmitted to the printer. The day prior to the issuance date, Monday, is actually the last day the approval can be withdrawn. Once the patent reaches this point in the approval process, however, it is extremely rare to have an approval withdrawn. 10 The abnormal returns we found are consistent with the procedure as set forth by the USPTO. The holder of the potential patent receives various cues from the USPTO that indicate an increasing certainty that the patent will be published and hence, approved. On days –15 and –16 the potential holder is sent official notification that the patent will probably be published. Since the USPTO reserves the right until the last minute to withdraw the patent from publication, it is not until the Gazette has been printed and awaiting delivery for the next day that the potential patent holder feels that the news is certain enough to warrant further disclosure to the market. Hence we found a reaction on day –1, not day 0, the day the Gazette is published. These findings suggest that the market perceives business patent approvals as having value for the business. 11 References 1st Circuit Court of Appeals, 1949, Loews Drive-In Theatres v. Park-In Theatres, Federal Reporter 2nd 174, 547. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals, 1908, Hotel Checking Co. v. Lorraine Co., Federal Reporter 160, 467. Albert, R. L. and T. R. Smaby, Market response to analyst recommendations in the “Dartboard” column: The information and price pressure e0ffects, Review of Financial Economics 5, 59-74. Amir E. and B. Lev, 1996, Value-relevance of non-financial information: The wireless communications industry, Journal of Accounting and Economics 22, 3-30. Anason, D., 1999, Financial firms given legal defense against lawsuits over patents, American Banker 164, 2:1. Brown, S. and J. Warner, 1985, Using daily stock returns: The case of event studies, Journal of Financial Economics 14, 3-31. Chartrand, S., May 1, 2000, A patent lawyer wins protection for a product intended to help other win protection for theirs, New York Times late edition, C.2. Cowan,A., 1992, Nonparametric event study tests, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 2, 343-358. Dempsey S., J. Gatti, D. Grinnell, and W. Cats-Baril, 1997, The use of strategic performance variables as leading indicators in financial analysts’ forecasts, Journal of Financial Statement Analysis, Summer, 61-79. Deng, Z., B. Lev, and F. Narin, 1999, Science and technology as predictors of stock performance, Financial Analysts Journal, May/June, 21-32. Dreyfus, R., 2001, Santa Clara Computer and High Technology Law Journal, forthcoming. 12 Ittner, C. and D. Larcker, 1998, Are nonfinancial measures leading indicators of financial performance? An analysis of customer satisfaction, Journal of Accounting Research 36 supplement, 1-35. Kovaleski, D., 2000, Patents for investment processes still unusual, Pensions and Investments 28, 3. Lev, B. and P. Zarowin, 1999, The boundaries of financial reporting and how to extend them, Journal of Accounting Research 37, 353-385. Lucchetti A., September 21, 2000, Patent poses problem for Amex exchangetraded funds, The Wall Street Journal, C1. McIntosh, N., June 21, 2000, E-finance: BT wakes up to chance of making hyperprofit, The Guardian, 1.27. O’Haver, R. and E. Rodgers, 2000, Financial service companies should protect their core intangibles, Corporate Finance April, 22-24. Reich-Hale, D., 2000, Suit raises question: Can patents protect business processes?, American Banker 165, 7. Schwartz, J., March 30, 2000, Online patents to face tighter review, The Washington Post, E1. United States Patent and Trademark Office, 2000, Automated financial or management data processing methods (business methods), USPTO White Paper, http://www.uspto.gov/web/menu/busmethp/index.html. United States Patent and Trademark Office, 2001, Manual of Classification, http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/def/705.html. Updike, E., October 26, 1998, What’s next—a patent for the 401(k)?, Business Week, 104. 13 Table 1. Sample of firms granted a Class 705 patent approval in class 35 and class 39 through December 31, 2000 with data available on CRSP tapes. Issue Patent # Date Assignee 5,884,28 16-Mar8 99 Sun Microsystems, Inc. (Palo Alto, CA) 6,018,72 25-Jan4 00 Sun Microsystems, Inc. (Palo Alto, CA) 6,073,11 3 6-Jun-00 Sun Microsystems, Inc. (Palo Alto, CA) 5,852,81 22-Dec2 98 Microsoft Corporation (Redmond, WA) 5,872,84 16-Feb4 99 Microsoft Corporation (Redmond, WA) 5,883,81 16-Mar0 99 Microsoft Corporation (Redmond, WA) 5,918,21 29-Jun6 99 Microsoft Corporation (Redmond, WA) 5,870,72 2 9-Feb-99 AT&T Wireless Services Inc (Middletown, NJ) 5,950,17 4 7-Sep-99 AT&T Corp. (Middletown, NJ) 5,963,62 5 5-Oct-99 AT&T Corp (New York, NY) 5,991,38 23-Nov0 99 AT&T Corp. (New York, NY) 6,052,67 5 18-Apr-00 AT&T Corp. (New York, NY) 6,064,97 16-May- AT&T Corp (New York, NY) File Date Permno Industry 9-Dec-96 10078 3570 30-Jun-97 10078 3570 29-Jun-98 10078 3570 23-Aug-95 10107 7370 18-Nov-96 10107 7370 24-Sep-97 10107 7370 22-Aug-96 10107 7370 22-Sep-95 10401 6711 25-Apr-97 10401 6711 30-Sep-96 10401 6711 21-Oct-97 10401 6711 21-Apr-98 10401 17-Sep-97 10401 6711 6799 1 Issue Patent # Date Assignee 2 00 6,125,34 26-Sep9 00 AT&T Corp. (New York, NY) 5,120,94 4 9-Jun-92 Unisys Corp. (Detroit, MI) 5,884,29 16-Mar0 99 Unisys Corporation (Blue Bell, PA) 5,949,88 0 7-Sep-99 Dallas Semiconductor Corporation (Dallas, TX) 5,696,90 7 9-Dec-97 General Electric Company (Schenectady, NY) 5,613,11 18-Mar3 97 International Business Machines Corporation (Armonk, NY) 5,878,23 3 2-Mar-99 International Business Machines Corporation (Armonk, NY) 5,991,41 23-Nov1 99 International Business Machines Corporation (Armonk, NY) 6,026,37 15-Feb4 00 International Business Machines Corporation (Armonk, NY) 6,064,99 16-May0 00 International Business Machines Corporation (Armonk, NY) 5,262,94 16-Nov1 93 ITT Corporation (New York, NY) 5,911,13 7 8-Jun-99 Motorola, Inc. (Schaumburg, IL) 6,144,94 9 7-Nov-00 Motorola, Inc. (Schaumburg, IL) 5,970,15 19-Oct-99 Pitney Bowes Inc. (Stamford, CT) File Date Permno Industry 30-Jun-98 10401 6799 10-Oct-89 10890 3573 22-Oct-96 10890 3573 26-Nov-97 11761 3674 27-Feb-95 12060 3634 7-Jun-95 12490 3573 7-Aug-95 12490 5410 8-Oct-96 12490 30-May96 12490 5410 31-Mar-98 12490 3573 30-Mar-90 12570 3662 15-Jul-96 22779 3663 12-Feb-98 22779 19-Dec-96 24459 3663 3579 3573 2 Issue Patent # Date Assignee 0 5,634,01 27-May2 97 Xerox Corporation (Stamford, CT) 5,839,11 17-Nov9 98 Xerox Corporation (Stamford, CT) 6,021,39 9 1-Feb-00 Xerox Corporation (Stanford, CT) 6,032,13 29-Feb5 00 Diebold, Incorporated (North Canton, OH) 5,717,86 10-Feb8 98 Huntington Bancshares Inc. (Columbus, OH) 5,787,40 3 28-Jul-98 Huntington Bancshares, Inc. (Columbus, OH) 5,899,98 2 4-May-99 Huntington Bancshares Incorporated (Columbus, OH) 5,902,98 11-May3 99 International Game Technology (Reno, NV) 6,167,38 26-Dec5 00 The Chase Manhattan Bank (New York, NY) 5,659,73 19-Aug1 97 Dun & Bradstreet, Inc. (Mary Hill, NJ) 5,765,14 4 9-Jun-98 Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc. (New York, NY) 5,826,24 3 20-Oct-98 Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc. (New York, NY) 6,016,48 18-Jan2 00 Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc. (New York, NY) 5,424,93 13-Jun- First Chicago Corporation (Chicago, IL) File Date Permno Industry 23-Nov-94 27983 3861 27-Sep-96 27983 3861 25-Nov-96 27983 3861 27-Apr-98 40440 3499 7-Mar-95 42906 6020 8-Mar-95 42906 6020 25-Jun-98 42906 6020 29-Apr-96 45277 3990 30-Nov-98 47896 6025 19-Jun-95 48506 7392 24-Jun-96 52919 6211 3-Jan-94 52919 6211 11-Jan-96 52919 13-Oct-92 53858 6211 6025 3 Issue Patent # Date 8 95 5,991,74 23-Nov8 99 4,794,53 27-Dec0 88 4,947,47 9 7-Aug-90 5,754,65 19-May6 98 5,880,44 6 9-Mar-99 5,963,92 6 5-Oct-99 5,991,74 23-Nov7 99 6,044,36 28-Mar3 00 6,058,38 2 2-May-00 6,155,48 4 5-Dec-00 5,907,83 25-May2 99 5,991,41 23-Nov2 99 6,061,66 4 9-May-00 6,076,07 13-Jun- Assignee File Date Permno Industry American Express Travel Related Services Company, Inc. (New York, NY) 6-Dec-96 59176 Hitachi, Ltd. (Tokyo, JP); Japanese National Railways (Tokyo, JP) 7-May-86 64231 6052 3569 Hitachi, Ltd. (Tokyo, JP) 25-Apr-89 64231 3569 Hitachi, Ltd. (Tokyo, JP) 1-Aug-96 64231 3569 Hitachi, Ltd. (Tokyo, JP) 29-Jan-97 64231 3569 Hitachi, Ltd. (Tokyo, JP) 4-Mar-97 64231 3569 Hitachi, Ltd. (Tokyo, JP) 26-Jul-96 64231 3569 Hitachi, Ltd. (Tokyo, JP) 2-Sep-97 64231 3569 Hitachi, Ltd. (Tokyo, JP) 10-Sep-97 64231 3569 Hitachi, Ltd. (Tokyo, JP) 10-Nov-98 64231 3569 Koninklijke PTT Nederland N.V. (The Hague, NL) 15-Nov-96 76616 5410 Koninklijke KPN N.V. (Groningen, NL) 9-Dec-96 76616 5410 Koninklijke PTT Nederland N.V. (NL) Koninklijke KPN N.V. (Groningen, NL) 9-Oct-96 76616 1-Mar-99 76616 5410 5410 4 Issue Patent # Date Assignee 3 00 6,154,72 28-Nov9 00 First Data Corporation (Hackensack, NJ) 5,797,13 18-Aug3 98 Strategic Solutions Group, Inc (Atlanta, GA) 5,889,86 30-Mar2 99 Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation (Tokyo, JP) 5,926,54 8 20-Jul-99 Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation (Tokyo, JP) 6,023,68 7 8-Feb-00 Capital One Financial Corporation (Glen Allen, VA) 6,049,78 4 11-Apr-00 Capital One Financial Corporation (Glen Allen, VA) 5,897,62 1 27-Apr-99 Cybercash, Inc. (Reston, VA) 6,092,05 3 18-Jul-00 Cybercash, Inc. (Reston, VA) 5,870,72 1 9-Feb-99 Affinity Technology Group, Inc. (Columbia, SC) 5,940,81 17-Aug1 99 Affinity Technology Group, Inc. (Columbia, SC) 6,105,00 15-Aug7 00 Affinity Technology Group, Inc. (Columbia, SC) 5,678,01 0 14-Oct-97 CompuServe Incorporated (Columbus, OH) 5,909,49 2 1-Jun-99 Open Market, Incorporated (Cambridge, MA) 6,049,78 11-Apr-00 Open Market, Inc. (Burlington, MA) File Date Permno Industry 19-Jun-98 77546 7373 3-Feb-97 79852 7370 15-Jul-96 80863 20-May97 80863 4813 30-Dec-98 81055 6141 16-Dec-97 81055 6141 14-Jun-96 83128 7370 7-Oct-98 83128 7370 15-Oct-96 83348 7370 15-Oct-96 83348 7370 5-May-99 83348 7370 7-Jun-95 83367 7374 18-Jun-97 83539 2-Mar-98 83539 7370 7370 4813 5 Issue Patent # Date Assignee File Date Permno 5 5,832,46 3 3-Nov-98 Electronic Data Systems Corporation (Plano, TX) 28-Mar-96 83596 6,049,78 1 11-Apr-00 Electronic Data Systems Corporation (Plano, TX) 18-Apr-96 83596 5,878,40 4 2-Mar-99 Mechanics Savings Bank (Hartford, CT) 8-Oct-96 83675 5,757,91 26-May7 98 First Virtual Holdings Incorporated (San Diego, CA) 1-Nov-95 84312 5,835,60 10-Nov3 98 NCR Corporation (Dayton, OH) 23-Sep-96 84372 5,987,43 16-Nov7 99 NCR Corporation (Dayton, OH) 23-Sep-96 84372 6,021,40 0 1-Feb-00 NCR Corporation (Dayton, OH) 2-Jan-97 84372 5,715,39 30-May9 3-Feb-98 Amazon.Com, Inc. (Seattle, WA) 95 84788 5,727,16 10-Mar3 98 Amazon.Com, Inc. (Seattle, WA) 30-Mar-95 84788 5,950,17 9 7-Sep-99 Providian Financial Corporation (San Francisco, CA) 3-Dec-96 85073 5,905,97 18-May- France Telecom (Paris, FR); La Poste (Boulogne Billancourt, FR); 6 99 Sintef Delab (Trondheim, NO) 17-Jul-96 85425 6,014,64 11-Jan6 00 France Telecom (Paris, FR) 5-Jun-96 85425 6,105,86 22-Aug2 00 France Telecom (Paris, FR); La Poste (Boulogne Billancourt, FR) 29-Oct-98 85425 5,893,08 6-Apr-99 Bottomline Technologies, Inc. (Portsmouth, NH) 25-Jul-95 86717 Industry 7379 7379 6030 7370 3574 3574 3577 7370 7370 6311 3663 3663 3663 7370 6 Issue Patent # Date 0 Assignee File Date Permno Industry 7 Table 2. Market adjusted average abnormal returns. We use a standard event-study methodology to estimate market-adjusted abnormal returns around the event date using the CRSP value-weighted index. We estimate abnormal returns over a 41-day event window from day –20 to +20 using the time series standard deviation method (Brown and Warner, 1985) to generate test statistics and report both the standard t-statistic and a generalized sign test. The null hypothesis for the sign test is that the percentage of positive returns is the same in the event window as the estimation period. Day -20 -19 -18 -17 -16 -15 -14 -13 -12 -11 -10 -9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Average Abnormal Return -0.27% -0.04% 0.29% 0.03% 1.06% 0.84% 0.19% -0.22% -0.29% -0.24% 0.51% -0.39% 0.76% -0.05% 0.19% -0.09% -0.55% 0.11% -0.46% 1.12% -0.03% 0.15% -0.08% -0.13% -0.13% 0.53% 0.34% -0.20% -0.18% 0.00% -0.17% -0.26% -0.38% -0.16% 0.41% -0.44% 0.10% Median Abnormal Return -0.47% -0.21% -0.35% -0.42% 0.11% 0.47% -0.26% -0.42% -0.48% 0.12% -0.17% -0.26% 0.28% -0.28% 0.52% -0.15% -0.75% -0.22% -0.49% 0.50% -0.12% -0.38% -0.38% -0.10% 0.19% -0.10% 0.50% -0.31% -0.12% 0.04% -0.30% -0.38% -0.66% -0.18% 0.34% -0.36% -0.33% t-statistic -0.45 -0.06 0.47 0.05 1.74** 1.39* 0.31 -0.37 -0.48 -0.40 0.83 -0.64 1.26 -0.08 0.31 -0.15 -0.90 0.18 -0.75 1.84** -0.05 0.25 -0.13 -0.21 -0.21 0.87 0.56 -0.34 -0.30 -0.01 -0.28 -0.42 -0.62 -0.27 0.68 -0.72 0.17 N 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 81 81 81 81 81 81 81 80 80 80 80 80 80 Positive: Negative 38:44 38:44 38:44 36:46 42:40 48:34 37:45 35:47 31:51 44:38 38:44 38:44 47:35 38:44 48:34 40:42 29:53 37:45 36:46 49:33 39:43 37:45 34:48 37:45 44:37 40:41 48:33 36:45 36:45 41:40 38:43 37:43 28:52 35:45 48:32 34:46 33:47 Generalize d Sign Test Z-statistic -0.06 -0.06 -0.06 -0.51 0.82 2.15** -0.28 -0.73 -1.61* 1.27 -0.06 -0.06 1.93** -0.06 2.15** 0.38 -2.05** -0.28 -0.51 2.37*** 0.16 -0.28 -0.95 -0.28 1.38* 0.49 2.27** -0.40 -0.40 0.71 0.04 -0.08 -2.10** -0.53 2.39*** -0.75 -0.97 1 17 18 19 20 0.04% 0.10% -0.23% 0.11% -0.18% -0.21% -0.08% -0.90% 0.06 0.16 -0.38 0.18 80 79 79 79 36:44 34:45 38:41 30:49 -0.30 -0.65 0.25 -1.55* *** Significant at the 1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. 2 Table 3. Market model average abnormal returns. We use a standard event-study methodology to estimate market-model abnormal returns around the event date using the CRSP value-weighted index. We estimate a market model for each firm during a 120-day estimation period from day –141 to day –21, and we estimate abnormal returns over a 41-day event window from day –20 to +20. We use the time series standard deviation method (Brown and Warner, 1985) to generate test statistics and report both the standard t-statistic and a generalized sign test. The null hypothesis for the sign test is that the percentage of positive returns is the same in the event window as the estimation period. Day -20 -19 -18 -17 -16 -15 -14 -13 -12 -11 -10 -9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Average Abnormal Return -0.39% 0.02% 0.14% -0.05% 0.91% 0.75% 0.13% -0.34% -0.42% -0.32% 0.42% -0.33% 0.69% -0.19% 0.01% -0.37% -0.59% -0.09% -0.66% 1.03% -0.07% 0.14% -0.23% -0.09% -0.22% 0.44% 0.20% -0.46% -0.24% -0.43% -0.28% -0.35% -0.62% -0.23% 0.39% -0.54% Median Abnormal Return -0.44% -0.07% -0.11% -0.29% -0.16% 0.34% -0.36% -0.46% -0.52% 0.04% -0.26% -0.14% 0.40% -0.19% 0.35% -0.32% -0.75% -0.22% -0.57% 0.28% -0.17% -0.12% -0.44% -0.18% 0.29% 0.06% 0.52% -0.20% -0.14% -0.15% -0.25% -0.53% -0.98% -0.16% 0.42% -0.56% t-statistic -0.66 0.04 0.24 -0.09 1.51* 1.25 0.22 -0.57 -0.70 -0.54 0.70 -0.54 1.16 -0.32 0.01 -0.62 -0.98 -0.15 -1.10 1.71** -0.12 0.23 -0.38 -0.15 -0.36 0.73 0.34 -0.76 -0.40 -0.72 -0.47 -0.57 -1.04 -0.39 0.65 -0.90 N 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 82 81 81 81 81 81 81 81 80 80 80 80 80 Positive: Negative 36:46 38:44 38:44 38:44 40:42 45:37 36:46 36:46 30:52 43:39 38:44 38:44 45:37 38:44 44:38 37:45 31:51 37:45 34:48 44:38 36:46 38:44 37:45 36:46 44:37 42:39 47:34 32:49 37:44 38:43 38:43 35:45 22:58 37:43 47:33 32:48 Generalize d Sign Test Z-statistic -0.46 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 0.42 1.53* -0.46 -0.46 -1.79** 1.09 -0.02 -0.02 1.53* -0.02 1.31* -0.24 -1.57* -0.24 -0.91 1.31* -0.46 -0.02 -0.24 -0.46 1.42* 0.97 2.09** -1.25 -0.14 0.08 0.08 -0.48 -3.40*** -0.04 2.21** -1.16 3 16 -0.01% -0.44% -0.01 80 17 0.06% 0.01% 0.11 80 18 0.10% -0.12% 0.16 79 19 -0.35% -0.30% -0.57 79 20 0.11% -0.79% 0.18 79 *** Significant at the 1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. 33:47 40:40 37:42 37:42 32:47 *Significant -0.93 0.64 0.07 0.07 -1.06 at the 10% level. 4 Table 4. Market adjusted cumulative average abnormal returns. . We use a standard event-study methodology to estimate market-adjusted abnormal returns around the event date using the CRSP value-weighted index. We estimate cumulative abnormal returns over three multi-day intervals using the time series standard deviation method (Brown and Warner, 1985) to generate test statistics and report both the standard t-statistic and a generalized sign test. The null hypothesis for the sign test is that the percentage of positive returns is the same in the event window as the estimation period. Days (-20, -2) (-1,0) (+1,+20) Cumulative Cumulative Average Median Abnormal Abnormal Return Return t-statistic 1.36% -0.09% 0.52 1.08% 0.27% 1.27 -0.56% -0.41% -0.21 Positive: Negative 41:41 44:38 37:45 Generalize d Sign Test Z-statistic -0.46 1.27 -0.28 *** Significant at the 1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. Table 5. Market model cumulative average abnormal returns. We use a standard event-study methodology to estimate market-model abnormal returns around the event date using the CRSP value-weighted index. We estimate a market model for each firm during a 120day estimation period from day –141 to day –21, and we estimate cumulative abnormal returns over three multi-day intervals. We use the time series standard deviation method (Brown and Warner, 1985) to generate test statistics and report both the standard t-statistic and a generalized sign test. The null hypothesis for the sign test is that the percentage of positive returns is the same in the event window as the estimation period. Days (-20, -2) (-1,0) (+1,+20) Cumulative Cumulative Average Median Abnormal Abnormal Return Return t-statistic -0.68% -0.61% -0.26 0.95% 0.34% 1.13 -2.59% -1.32% -0.97 Positive: Negative 40:42 44:38 30:52 Generalize d Sign Test Z-statistic -0.46 1.31* -1.79** *** Significant at the 1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. 5 Figure 1. Plot of cumulative abnormal returns for the market-adjusted and market model. 4.0% 3.0% 1.0% Mkt Adj Mkt Mod 20 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 -6 -8 -1 0 -1 2 -1 4 -1 6 -1 8 0.0% -2 0 CAR (%) 2.0% -1.0% -2.0% -3.0% Day 6