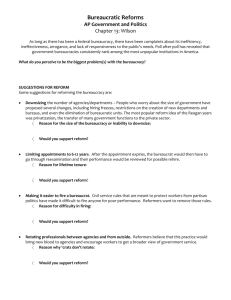

Flagship Bureacracies

advertisement