MSU Teaching Thoughts 2009/2010

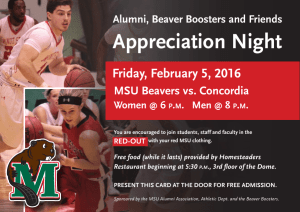

advertisement