Three Case Studies - ElderSpirit Community

advertisement

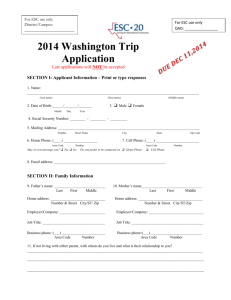

ElderSpirit Community Aging in a Community of Mutual Support and Spiritual Growth: The Case of ElderSpirit Community Corresponding Author: Anne P. Glass, Ph.D. Assistant Director, Institute of Gerontology Assistant Professor, Health Policy & Management College of Public Health University of Georgia 110 Slaughter Building 255 East Hancock Avenue Athens, GA 30602-5775 aglass@geron.uga.edu 706-425-3222 1 ElderSpirit Community 2 Acknowledgements: Both ElderSpirit Community and this research have received grant support from the Retirement Research Foundation. The author would like to highlight the important role of several individuals in making ElderSpirit Community a reality, including Dene Peterson, Catherine Rumschlag, and Kathy Hutson. Monica Appleby, Anne Leibig, and Jean Marie Luce worked with the author in 2001 to create the model of late life spirituality included in this article. Special thanks go to Monica Appleby, a resident of ESC, for opening up her home to the author during on-site research and coordinating the interview schedule. The author appreciates all the residents of ESC who generously agreed to give of their time to participate in the study. Finally, the author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Marilyn Schroeder with data management and helpful comments on the manuscript. ElderSpirit Community 3 Aging in a Community of Mutual Support and Spiritual Growth: The Case of ElderSpirit Community Abstract Purpose: This article describes an innovative alternative now emerging for older adults: the elder-only cohousing community. ElderSpirit Community (ESC) in Virginia, among the first such communities in the U.S., is a resident-managed, mixed-income, mixed-ownership model, focusing on mutual support within a broad spiritual context. This portrait of ESC’s origin and “charter residents” demonstrates that elders can proactively preplan to intentionally live “in community” to help take care of themselves. Design and methods: The overall project design of this case study includes a collection of baseline descriptive data followed by a three-year longitudinal study. An ethnographic approach with in-depth interviews is being used to understand how this opportunity to live in community is interpreted by residents. Baseline quantitative data collected via a written questionnaire are reported here. Results: The sample of 32 residents was white and most were female (78.13%), with an average age of 70.38 (range: 63-84). Compared to the general older population, they were more likely to be childless and to be divorced or never married. They were diverse in religion and occupational backgrounds and, similar to European cohousers, largely homogeneous in social class, education, and race. They were unlike cohousers with their generally lower income levels. Implications: The desire for alternatives to nursing homes and the shortage of traditional caregivers make this study important. Little research has been done on elder non-kin caregiving, but mutual support was a significant motivation to choose ESC. Lessons learned from ESC may help facilitate “aging in community.” (245 words) KEYWORDS: nonkin caregiving, cohousing, sense of community ElderSpirit Community 4 Aging in a Community of Mutual Support and Spiritual Growth: The Case of ElderSpirit Community Introduction A growing number of older adults and baby boomers are rebelling against the threat of spending their final years lonely and bored, wondering who will take care of them, and ending life in a conventional nursing home. A new alternative now emerging is the intentional cohousing community for elders. This article describes the origin of one of the first such communities, ElderSpirit Community (ESC) in Abingdon, Virginia, which opened in 2006, and provides a portrait of the “charter residents” of ESC. ESC is additionally unique as it is the only low to moderate income and mixed ownership elder cohousing community in the United States. Cohousing has existed in the United States for over 30 years, but is only now being adopted for elder-only communities. Cohousing communities are characterized by resident management and decision making (Durrett, 2005) and are designed to encourage a sense of community among residents. With these attributes, elder cohousing has the potential to provide a better quality of living for many older adults. ESC is the vanguard of a nascent movement that has recently gained a name: “aging in community.” Another goal of some elder cohousing communities, which could prove to become a benefit with significant consequences, is the provision of mutual support. The population over 65 will double by 2030, but the population of traditional caregivers – generally women in the middle age ranges – will increase only slightly during the same period (Day, 1996), and the baby boom generation is more likely than past generations to have only one or no children (Gironda, Lubben, & Atchison, 1999; National Center for Health Statistics, 2005). With the shortage of traditional caregivers already beginning to cause challenges, the question of whether elders could possibly help take care of each other becomes a very important area of research. In the United ElderSpirit Community 5 States, where there is such an emphasis on independence, we seldom choose to live in a group setting, but this arrangement might be exactly what is needed when we are low in resources. Furthermore, many elders fail to plan ahead and instead wait until a crisis occurs that makes them dependent, and they wind up in institutions. There is little work thus far that has explored the potential of non-kin, non-paid caregiving (e.g., Barker, 2002; Johnson & Barer, 1990), especially among older peers. How do we cultivate and nurture such care? These questions are among those to be addressed in the case study of ESC as it evolves. What is already proven, and will be demonstrated in this article, is that preplanning can occur, and elders can proactively choose a new option: living and aging intentionally “in community.” The Elder Cohousing Concept Cohousing communities are especially designed to encourage the development of a sense of neighborhood and community. McCamant and Durrett (1994) are credited with coining the term “cohousing” and launching the idea in the United States in the 1970s. Since that time, intergenerational cohousing communities have developed in at least 21 states, with about 5,000 Americans living in over 90 cohousing communities (Perrigan, 2006; Williams, 2005). The original cohousing concept is associated with Denmark, although similar communal living developments could also be found in Sweden and the Netherlands during the same period (Meltzer, 2005). Key common features identified by Fromm (1991) and cited in Brenton (2001) include: “common facilities; private dwellings; resident-structured routines; resident management; design for social contact; resident participation in the development process; and pragmatic social objectives” (p.171). While cohousing has been touted as a solution to empower women and single parents (Horelli & Vespa, 1994), and to overcome suburban alienation (Scanzoni, 2000), relatively little has been written about the role of cohousing for older adults. ElderSpirit Community 6 The research literature that does exist focuses on developments outside of the United States (see for example, Andresen & Runge, 2002; Brenton; Choi, 2004). Elder cohousing is more common in Europe; there are 2,800 elder cohousing units in Sweden and 2,100 in the Netherlands, with at least 28 such communities (Choi, 2004) in Denmark and Sweden. In these countries, it is not viewed as an alternative to the nursing home, but residents may receive home help around the clock, if needed. It is also possible that neighbors will provide support to each other, and in fact, residents do appear to help each other more than in conventional housing (Choi, 2004). A pilot group in the United Kingdom was described as advantageous because “it is addressing the challenge of ageing society in promoting continued independence, an active life and mutual support by means of a self-help formula which should reduce demands made on local services” (Brenton, 2001, p. 183). As a group, older adults in the Dutch CoHousing Communities committed to the concept of mutual support for their members (Brenton, 2001). About 200 communities have formed since 1981, ranging from six to 70 units. In their experience, the number most conducive to promoting this sense of community is between 30 and 40 individuals. Women outnumber male residents about three to one, and the average age is approximately 70. Most European older cohousers are among the relatively “young old.” An overview of Danish elder cohousing shows the average resident age is 62 at the time of moving in (Andresen & Runge, 2002) and the average age of residents overall is 70 (Choi, 2004), similar to the Dutch. Limited early research in Europe shows that residents feel positively about both the social and physical environment (Andresen & Runge) and the majority (75.7%) would strongly recommend this option to others (Choi). Much has been written about the physical design of intergenerational cohousing communities (Durrett, 2005; Meltzer, 2005; Williams, 2005) and the usage of social contact ElderSpirit Community 7 design (SCD). The neighborhood design and the inclusion of communal facilities, such as a common house where meals can be shared, are key elements. The common house may also contain a mail room, a laundry, a crafts room, and other features, with the goals of promoting the interaction of residents as well as sharing space and function in order to live more simply. The community is also typically designed with green space between the houses, rather than a paved street in the center, in contrast to the traditional suburban neighborhood where people drive home, park in their garages, and may not see their neighbors at all. Cars in cohousing communities are parked away from the units; some communities are car free (Williams). The notion of sharing facilities, such as washing machines and televisions, is also part of the philosophy of cohousing. Generally, cohousing residents are interested in living more gently on the land; thus there is often a lesser emphasis on materialism and ownership (Marcus & Dovey, 1991; Meltzer, 2005; Williams, 2005). Building the units close together and sharing common green spaces are another part of this orientation. Units are typically smaller than average, with the idea that some functions can be conducted in the common spaces. Among the other features characteristic of cohousing (Durrett, 2005; Fromm, 1991), there are four of note that are organizational. The first is a participatory process, which optimally begins before or during the design phase. Second is resident management, and the third is nonhierarchal structure and decision making. In many communities, decisions must be reached by consensus, which may require more effort than simply voting on issues. The fourth feature is that there is no shared community economy, which separates this model from the traditional “communes.” ElderSpirit Community 8 Making the Elder Cohousing Concept Operational A small group of pioneers launched an experiment in the rural setting of Abingdon, Virginia, to provide an alternative to traditional options for older adults: a community of mutual support. They created ESC, one of the first two elder cohousing communities in the nation. The first is Glazier Circle in Davis, California, which opened in December 2005, and a third, Silver Sage, opened in October 2007, in Boulder, Colorado. The first residents began to move into ESC in February 2006. Philosophical and Cultural Dimensions The founders of ESC are members of a community service and action group called the Federation of Communities in Service (FOCIS), which has been in existence since 1967. One member, Dene Peterson, challenged the group to think about how they would like to live as they got older. A committee was formed in 1995 called FOCIS FUTURES. They recognized that not all caregiving answers are going to come from families and corporations, and they were the catalyst for the development of ESC. Inspired in part by an article by Drew Leder (1996) about spiritual communities for elders, the founders have made ESC unique from other options for older adults in several ways. First, ESC was created by a group of elders who had a vision, wanted something different, participated in the planning and design, and created the reality, overcoming many obstacles along the way. Second, they chose to use the cohousing format, which had not been previously tested in an elder-only model; other cohousing in the United States has been intergenerational. Third, ESC is designed for moderate to low income residents, again an anomaly as most cohousing, and indeed, most traditional retirement communities, target middle to higher income individuals. Fourth, it is self-managed by the residents and encompasses both ElderSpirit Community 9 owners and renters in the same community. Consistent with the cohousing model, there is no shared economy. Fifth, ESC invokes an emphasis on spirituality, described as a “dynamic process involving openness to activities of one’s soul or spirit that foster a sense of meaning and purpose in life” (ESC brochure, 2005). Finally, and arguably most importantly, ESC aspires to be a community of mutual support. This project differs from the past because such an intentional cohousing community for elders has never before existed in the United States. Their mission statement (ESC website, 2007) reads: ElderSpirit Community is a participatory membership organization for older adults that provides opportunities for growth through later life spirituality programs and the formation of communities and residential centers. Consistent with the characteristics outlined in overviews of Danish and Dutch elder cohousing (Andresen & Runge, 2002), ESC is newly-built and units face the common area. It has 29 units, comparable to the Danish average of 20 to 30 units, where they found 24 units to be ideal in size (Brenton, 2001). At ESC, the 13 owned houses are one story and grouped in duplexes and triplexes on one side of the common green space, while there are two floors of rental units in two separate buildings on the other side. The latter design was determined by the steepness of the site, which allows all units to be entered from ground level. The units on the upper level have parking at the door, while all other residents must park in lots at either end of the community. Four small apartments are in the common house and were completed after the other units. The common house is toward one end, rather than in the middle. Residents may have gardens in front or back of their units; they may also have additional garden plots in a community garden. Additionally, there is a house adjacent to the ESC property in which two FOCIS members have lived for several years as the plans for ESC developed and became a ElderSpirit Community 10 reality. Two other women have recently moved into an apartment in this house as well, drawn by the ESC model. While physically located slightly “up the hill” from ESC, these four individuals are very involved with and part of the cohousing community; in effect, adding two more units to make the total number of 31. As part of an early visioning process, five years before ESC took physical form, a model of Late Life Spirituality, broadly defined, was created (see Figure 1). A review of relevant literature was conducted, but no adequate model was found to be of use for the desired purpose. Thus, a model was created by Monica Appleby, Anne Leibig, and Jean Marie Luce, working with the author, as an ESC Strategic Planning Task Force. In this model, six dimensions of spirituality are identified: Inner Work, Caring for Oneself, Mutual Support, Community Service, Reverence for Creation, and Creative Life. These six dimensions are viewed as the embodiment of the values of ESC and aspects of each dimension are outlined. In addition, examples of how these dimensions might be “lived out” are included in the “exemplified by” section. This model was part of an effort to begin to articulate how ESC might look, and provides a conceptualization of the underlying philosophy. The concept of mutual support has been further described by Appleby, Leibig, and Luce as part of an ESC Extension Project to be a dynamic relationship that involves three actions/interactions: (1) care of self, (2) asking for support, and (3) giving support. [Figure 1 about here] Associated with this model, a “Goodness of Fit” tool (see Figure 2) was developed to help elders decide if this type of community might be appropriate for them. This tool is included on the ESC website as well as in the application packet, and can be used by interested individuals to “self-select” those who are looking for a community that holds the values outlined in the spirituality model. ElderSpirit Community 11 [Figure 2 about here] Before construction began, many efforts were made by those associated with ESC to involve potential residents through courses, retreats, informal meals and get-togethers, and formal planning sessions. These efforts created opportunities to begin to build a sense of community during the lengthy construction period. Potential residents also had opportunities to play a role in the design process, and in fact, owners were given many individual choices in the construction and lay-out details of their units. An avowed hope of ESC founders was that residents could remain at home until they died, if at all possible. Will neighbors help with hands-on care when that time comes? While some researchers (Jason & Kobayashi, 1995) believe that the “sense of community” has diminished in our society over time, elder cohousing offers a way to build and strengthen that sense. In the Danish cohousing study, “Being close to each other also implies taking part in the happy events of each other’s lives as well as in more sorrowful times” (Andresen & Runge, 2002, p. 161). Can a group of elders develop a sense of community that will be strong enough to see them through difficult times? The answers to these questions are crucial to the well-being and quality of life for those adults in their later years. Design and Methods The first residents began to move into ESC during February 2006. In order to interview and collect baseline data on these residents, I approached the ESC Residents’ Association with the idea for a study, and received full cooperation from ESC residents in this project. I have even been able to stay with a resident on-site while conducting the research, allowing additional opportunities to observe the community. My interview guide was developed with input from a team of ESC residents, with whom I met prior to starting the on-site study. The fact that the ElderSpirit Community 12 researcher has already established good rapport with and been accepted by the ESC residents is significant, particularly as a few respondents referred to the fact that some residents have begun to truly feel like “an experiment.” ESC has been the subject of attention and visiting from many quarters, having been featured in the New York Times (Brown, 2006), Wall Street Journal (Greene, 2006), Time Magazine (Abrahms, 2006), and other national news media. The researcher obtained Human Subjects approval from the University of Georgia Institutional Review Board to conduct these interviews and surveys. An informed consent form is reviewed and must be signed by each participant before an interview is conducted. Confidentiality and anonymity are assured; no actual names are used in any reports or publications, other than possibly those that are already public knowledge, such as the names of the founders. Even in this case, names will not be associated with any specific quotations or comments without permission. Research Design This case study is, in effect, an implementation evaluation, which is appropriate for the study of a new and innovative model program. The basic project design is to complete the collection of baseline descriptive data and then to conduct a longitudinal study over a three year period. As ESC is a new experiment, the ethnographic and open-ended approach of in-depth interviews is used to gain an understanding of the way this opportunity to live “in community” and to provide mutual support was chosen and how it is interpreted by the residents. The qualitative aspect is appropriate when little is known about a phenomenon and the goal is to gain an understanding of how individuals interpret their experience (Creswell, 2003). Intensive interviews and long-term involvement and observation promote the collection of “rich” data. Using mixed methods, the researcher conducted both in-depth interviews and, to allow additional ElderSpirit Community 13 comparisons, “quasi-statistics” (Becker, 1970) were also collected via a short written questionnaire. Residents were informed about the research project by members of the ESC Residents’ Association. All participants received written information explaining the project and their voluntary choice to participate. All interviews were performed face-to-face after reviewing the informed consent form and obtaining the signature of each participant. The interviews were audio taped and lasted about 45 minutes on average; the maximum was 80 minutes. Participants were then asked to complete the survey questionnaire. The data was analyzed by two researchers to promote accuracy. Data Collection and Analysis I piloted an interview instrument in an on-site study in the summer of 2006. Using mixed methods, I conducted in-depth interviews and collected data from all but one of the 22 residents who moved in during the first six months. This number included the two women who have lived for seven years in the house adjacent to the newly built cohousing community, as they are FOCIS members who have a long involvement with ESC and are very much a part of the community. In July 2007, I returned to complete interviews with the remainder of the “charter residents” who had subsequently moved in, and also conducted a second interview with the 2006 participants. Of the 39 individuals who are considered to be the first residents of each of the 31 units, 32 were interviewed. Four chose not to participate, two were unable to participate due to absence, and one had not yet moved in as of the time of the second interview collection. The results of the quantitative data collected from the survey questionnaires were compiled into matrices and analyzed using basic descriptive statistics as presented here for the sample of 32. The Initial Survey ElderSpirit Community 14 Each participant completed a short survey questionnaire which addressed basic demographics such as age, education, and occupation. In this survey, the researcher also queried participants about their support systems – parents, children, siblings, and close friends – and their proximity and frequency of contact. Further inquiries about which aspects were most important in their decision to move to ElderSpirit Community were included, as well as items about functional status and health, in order to obtain baseline data. These results can be compared to data from other groups and the general population, and will also be compared to further data collected longitudinally at ESC. Results Initial survey findings shared here provide a baseline description of a sample of the first residents to live at ESC. They indicate that it is a white (n = 32) and primarily female (n = 25, 78.13%) population, with all but one of the seven males involved in marital relationships with female residents. Of the total sample interviewed, 11 (34.38%) were married (or in one case married, then divorced, but still living together), 8 (25.00%) were widowed, 7 (21.88%) were divorced, and 6 (18.75%) were never married. The average age of the residents was 70.38. The ages ranged from 63 to 84, with 18 (56.25%) in the 60-69 age group, 10 (31.25%) in the 70-79 group, and four (12.50%) aged 80 or over (see Table 1). The average level of education reported is almost five years above high school graduation. Only one person reported less than some college, with half of the participants (n = 16) having graduate degrees. Of the 31 who responded when asked if they considered themselves “outer-directed” or “inner-directed,” 11 (35.48%) identified as “outer-directed” or extroverted, 15 (48.39%) as “inner-directed,” or introverted, and 5 (16.13%) reported they were a combination of the two. [Table 1 about here] ElderSpirit Community 15 The variety of occupations reported reflects the diversity among elders. If such a wide range of occupations can be categorized, nineteen (59.38%) fell into the category of commercial or business, ten (31.25%) into the category of human services, and three (9.38%) as “other.” Occupations represented included community developer, office worker, teacher, administrative assistant, minister, city manager, clerk, activist, design engineer, librarian, bookkeeper, therapist, cook, meteorologist, naturopath, self-employed, photographer, business executive, business consultant, and auto body repairman. Residents were also asked to report their household income within given ranges: thirty residents responded to this question. Six (20.00%) reported income below $20,000 per year; 13 (43.33%) between $20,000 and $35,000, 8 (26.67%) between $35,000 and $55,000, and three between $55,000 and $75,000 (10.00%). None reported income above $75,000. Despite the origins of ESC within the FOCIS group, only five of the charter residents were members of that group, and residents migrated from all over the United States to become a part of ESC, even without previously knowing anyone there. Retreats that had been held prior to the opening helped spread the word about the new community. The charter residents of ESC came from 14 different states. Two-thirds (n = 21, 65.6%) came from the Southeast. Four came from the Midwest, five from the Northeast and two from the West Coast. States represented included CA, FL, IL, KY, ME, MI, NC, NH, NY, PA, TN, VA, WI, and WV. Social Networks In exploring relationships, only one resident reported a living parent. As far as children, the mean was 2.34 (range = 0 to 7) with over one quarter (n = 9, 28.13%) of the respondents reporting they never had children. Of the 23 who reported having living children, 17 (73.91%) stated they communicated weekly with at least one child, and six (26.09%) did not. Almost all ElderSpirit Community 16 residents (n=28, 87.5%) reported having siblings; one reported three step-siblings; four never had siblings at all. The mean was 2.6 (range = 0 to 14), with two respondents stating they had only one sibling and that sibling had died. Overall, eleven (34.38%) had lost at least one sibling to death. Of the 26 (81.25%) of the sample who had living siblings, 8 (30.77%) communicated weekly with at least one and 18 (69.23%) did not. When asked how many self-defined “very close friends” they felt they had in their lifetime, the mean was 6.84. Most reported ten or fewer; the range was one to 30. About one-third (n = 10, 31.25%) reported having lost some of their close friends to death, yielding a mean of 5.5 living friends. Ten (31.25%) reported they did not communicate with any of their friends regularly on a weekly basis; the remaining 22 (68.75%) did report weekly communication. When asked the question, “If you needed help with your home and personal care due to a health problem, how likely would you be to ask any of these individuals to help you?”, a significant pattern emerged indicating that participants are definitely counting on their neighbors within ESC for assistance. Over 80 percent (n = 26, 81.25%) reported they were “very likely” to ask other ESC residents for help, compared to one-third (n = 11, 34.38%) who would very likely ask their children (see Table 2). Adding the “Somewhat likely” category to the “Very likely” category shows that all but one participant expect to ask their ESC neighbors for assistance. Eight (25.00%) reported being “very likely” to ask other friends outside of ESC, and even fewer (n = 5, 15.63%) reported being “very likely” to ask their siblings. Among all residents, 14 (43.75%) named two sources of support as “Very likely,” 13 (40.63%) named only one, three (9.38%) individuals named three, and two (6.25%) residents did not consider any of these sources as “Very likely.” [Table 2 about here] ElderSpirit Community 17 Health Of arthritis, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and cancer, only three of 31 (9.68%) participants reported having none of these chronic conditions. Fourteen (45.16%) reported only one, 10 (32.26%) had two, and four (12.9%) had three of the conditions. High blood pressure and arthritis were the most common, with half the residents reporting one or the other or both of these conditions (see Table 3). (Since some respondents had multiple conditions, the total does not equal 31.) . [Table 3 about here] Over half (58.07%) of the 31 participants who responded to the question self-reported their physical health as “excellent” or “very good,” while even more (n = 21, 67.74%) selfreported their mental health as “excellent” or “very good” (see Table 4). No participants reported their physical or mental health as “poor.” When asked to compare their health to one year ago, five (16.13%) and eight (25.80%) reported improvements in their physical and mental health, respectively; four (12.90%) reported worsening of their physical health and only one reported a worsening of mental health (see Table 5). [Tables 4 and 5 about here] Generally, respondents reported they were independent with their basic and instrumental activities of daily living. Two respondents reported that the only help they needed was the use of assistive devices when walking. Two other respondents needed some help with at least one activity, at least temporarily, particularly one participant who had sustained a hospitalization since moving in. All respondents reported having a car. ElderSpirit Community 18 Reasons for Decision to Move to ElderSpirit Community Respondents were asked to rate the importance of several possible reasons in making the decision to move to ESC, with 1 equal to “Not important at all,” and 5 equaling “Extremely important.” They were then asked which one reason was most important to the decision. Table 6 shows the reasons ranked by mean score, along with the number who chose that item as the most important factor to their decision making. “Sense of community” and the idea of “mutual support” were ranked most highly; a simplified lifestyle and the spiritual component were also strongly valued. [Table 6 about here] Considering the importance of the spiritual component in choosing to move to ElderSpirit Community, it is notable that respondents reported a wide range of answers when asked to describe their religious affiliation. Religions/churches that were represented included Catholic, Eastern/Hindu, Episcopal, Methodist, and Unitarian Universalist, and several respondents reported they had no religious affiliation or made other comments regarding their spirituality such as, “open,” “very connected,” and “greater force.” Discussion This description of the charter residents of ESC presents a diverse population in many aspects. They migrated from all over the United States to this community in rural Virginia, from as far away as California. While broadly defined spirituality is a drawing card of the community, as outlined in the model of later life spirituality (see Figure 1), no one religion or belief is dominant among the residents. The diversity of occupations represented by the sample is consistent with the report of the Danish researchers (Andresen and Runge, 2002), who state in their overview of earlier European studies that “It is very common that residents have very ElderSpirit Community 19 different backgrounds in employment: craftsmen, academics, teachers, housewives, etc.” (p. 157). This population, however, while diverse in many ways, is for the most part homogeneous in terms of social class, education, and race, fitting the description of traditional cohousers by Williams (2005), who further notes that homogeneity within a community encourages social interaction. They are like traditional cohousers in that they are mostly well educated (Meltzer, 2005), but unlike cohousers with regard to their generally lower income levels. As in the Dutch elder cohousing (Brenton, 2001), women outnumbered men three to one. A concern among elder cohousers is the ability to “future-proof” their community (Brenton, 2001). Future-proofing requires that there are both “young-old” residents as well as older residents in the community. If all residents are in the same age range, they will all age in place together and it may eventually become difficult to attract new younger residents to keep the community vibrant and functioning well. Many European elder cohousing communities make an effort to incorporate a mix of ages, beginning with some residents in their 50s (Brenton). For example, a community in Nijmegen in 1997 had 20 residents in their 50s, 15 in their 60s, and 13 in their 70s. At ESC, there is a greater than twenty-year span in ages, ranging from 63 to 84. The distribution pattern is similar to the Nijmegen model, except that the groups are each a decade older, starting in their 60s rather than the 50s. Their average age at move-in of 70.38 is above the average age of 62 reported in the Danish studies (Andresen & Runge, 2002). The percentages (about half of the sample) who had the two health conditions most common among older adults were similar to the 2004 – 2005 national averages among the general older population, who reported 48 percent with hypertension and 47 percent with diagnosed arthritis (Greenberg, 2006). The percentage in the sample reporting cancer was also ElderSpirit Community 20 comparable to the national average of 20 percent, while the percentages reporting diabetes and heart disease were lower than the national averages of 16 percent and 29 percent respectively. Over half the participants self-reported their physical health as “excellent” or “very good,” while two-thirds self-reported their mental health as “excellent” or “very good.” These percentages are notably higher than the national average for noninstitutionalized older adults considering themselves in excellent or very good health, which has recently been variously reported as between about 25 percent (National Institute on Aging, 2007) to 38.3 percent (Greenberg, 2006). These findings suggest that, while the sample population has not escaped the common chronic conditions that often accompany aging, they are more likely then the general older population to consider themselves as very healthy. It was striking that only one resident reported a living parent. The percentage would be expected to be higher, especially for those in their sixties; nationally at least 10 percent of those over age 65 have living parents (Nussbaum, 1997). It is likely that freedom from the responsibilities of caregiving for their parents may be key to allowing respondents to choose to move to an experimental community such as ESC. The sample is also less likely to be married, compared to over half (53.2%) of those age 65+ nationally (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006), and less likely to be widowed compared to the national average of 31.7 percent. Conversely, the sample had higher percentages of those who are divorced and particularly of those who never married, compared to 9.3 percent and 4.6 percent, respectively, of the national population. The percentage in the sample who reported no children was also high compared to national data, which shows that for all age groups age 55 and above, including those age 85 and above, between 85 and 90 percent have children (National Institute on Aging, 2007). The sample appears to be at or above average in the percentage who ElderSpirit Community 21 reported having living siblings. A 1996 study showed 88.7% of those 65 to 74, 76.3% of those 75 to 84, and 50.0% of those 85 and above had living siblings (Bedford & Avioli, 2001). Mutual support was clearly identified as a driving reason for individuals to choose to move to ESC, and a large majority of participants identified “friends within ESC” as the part of their social network that they are “very likely” to call upon if help with home or personal care were needed due to a health problem. Not only does this finding confirm the possibility of nonkin caregiving, but it reinforces the importance of ESC choosing to focus on mutual support. As far as kin versus nonkin support, some research (Felton & Berry, 1992) suggests that kin are preferred for certain kinds of support, especially “reliable alliance,” defined as instrumental assistance. When older adults do make substitutions of nonkin for kin, however, at least some of the substitutions “leave them as advantaged by those replacement social relationships as by the original, or preferred, source” (p. 95). The fact that respondents were twice as likely to communicate regularly with friends than with siblings suggests further support for the notion of “fictive kin” (Jordan-March & Harden, 2005), and our closeness to those “families” we choose for ourselves. Even as residents’ conditions worsen, with the support of concerned neighbors and supplemental home care and hospice, many will potentially be able to remain at home, and out of institutions. A “buddy system” has already been established – and used – and the participants report security in knowing they always have a neighbor they can call if they need assistance at any time, 24 hours a day. This scenario could provide a better and more satisfying experience for the residents. While expectations about mutual support garnered from the interviews will be reported in a future article, previous studies of intergenerational cohousing indicate that “mutual support networks and social relations are stronger and more developed in cohousing ElderSpirit Community 22 communities than in standard residential areas” (Williams, 2005, p. 147). Studies of European elder cohousing have also cited the residents’ satisfaction with the security provided by their neighbors (Brenton, 2001). Furthermore, service to others becomes a priority for many older adults. Interestingly, it appears that elders who support others may actually gain more themselves in health benefits than those who receive the help (Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, & Smith, 2003). One limitation of this study is the lack of a matched control group. Efforts are underway, however, that will allow for future comparisons. A source of potential bias should also be recognized in this study, in that I did have a prior consulting relationship with the founders of ESC and was involved with the development of the Model of Late Life Spirituality as well as the Goodness of Fit documents. Since none of us are completely without bias in some form, the possibility that I have some bias with regard to the community must be noted, despite my efforts to be objective. Five years passed before I again became involved with ESC, however, and only after the residents began to move in. On the positive side, my early connection helped provide an “entrée” into ESC, and having one of the residents, with whom I had previously collaborated, then help arrange the schedule of interviews likely facilitated the establishment of trust between the interviewer and the respondents. It could also be argued that my knowledge and understanding of the history of how ESC came into existence and of the individuals involved, which the majority of the residents do not know, gives additional insight that few others would possess. ESC provides multiple advantages compared to other elder housing choices. Being able to self-govern in a community of peers, instead of having someone telling you what to do, is a radical idea for this age group in our society. In the interviews, to be documented in future articles, respondents reported feeling affirmed through the sense that they are valued and capable ElderSpirit Community 23 of being productive, worthwhile, and important to others, no matter what their condition. They have proven they can proactively choose a style of living that offers an innovative approach to caring for themselves and each other. Cohousing also provides the twin opportunities of being able to easily engage with others, but to also be able to return to one’s own home when time alone is desired. Several community theorists cited in Williams (2005) suggest that, …resident involvement in the development and operation of communities, nonhierarchical social structures, formalized social activities, and common goals are instrumental in developing strong social networks and increasing the cohesiveness of communities (p. 154). Support for cohousing comes not only from community theorists, but also from social theory (Gans, 1967; Homans, 1968), environment-behavior theory (Meltzer, 2005), and social capital theory (Pretty and Ward, 2001). It is likely that elder cohousing can also promote “communal coping” (Lawrence & Schiller-Schigelone, 2002) with the challenges of aging, thereby potentially helping residents have better aging experiences. The qualitative interviews gave some indications that such communal coping was already occurring. While ESC is among the first, other intentional cohousing communities specifically for older adults are sprouting up in other parts of the country. One definition of a movement is when related phenomena are emerging independent of each other, as is happening at this moment. At this point, there is no “cookie cutter” pattern for such communities and they are already showing intriguing permutations. The experience of residents in elder-only cohousing communities could also be compared with those who live in intergenerational communities, and some will be built ElderSpirit Community 24 adjacent to intergenerational models, as the elder-only Silver Sage was built next to the intergenerational Wild Sage neighborhood in Boulder, Colorado. The overall goal of the larger study is to determine if this intentional elder cohousing community succeeds in meeting expectations and maintaining or improving quality of life for the residents, through exploration of provision of care by neighbors, self-reported health, satisfaction, social network development, “communal coping,” and the role of spirituality and sense of community. Can an intentional cohousing community for elders evolve in such a way that individuals, perhaps previously unknown to each other, handle the challenges of living in community and willingly help their neighbors? Whether ESC succeeds or not, what we discover from the evolution of this first community may affect the lives and choices of many elders in the future. Will ESC be “one-of-a-kind,” or the birth of a new movement that offers dignity, respect, and an element of spirituality through mutual support, for elders who proactively preplan and take action? There are many questions, and few answers. Lessons learned from ESC may help others avoid possible pitfalls and obstacles, and facilitate this movement of “aging in community.” ElderSpirit Community 25 References Abrahms, S. (2006, October 23). Not home alone. Time Magazine. Retrieved October 27, 2006, from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1549300-2,00.html Andresen, M., & Runge, U. (2002). Co-housing for seniors experienced as an occupational generative environment. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 9, 156-166. Barker, J. C. (2002). Neighbors, friends and other nonkin caregivers of community-living dependent elders. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 57B, 3, S158-S167. Becker, H. S. (1970). Sociological work: Method and substance. Chicago, IL: Aldine. Bedford, V. H. & Avioli, P. S. (2001). Variations on sibling intimacy in old age. Generations, 25 (2), 34-40. Brenton, M. (2001). Older people’s cohousing communities. In S.M. Peace & C. Holland (Eds.), Inclusive housing in an ageing society: Innovative approaches (pp. 169-188). Bristol, UK: Policy Press. Brown, P. L. (2006, February 27). Growing old together, in new kind of commune. The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2006 from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/27/national/27commune.html?ex=1298696400&en=a3 89effcc8c0675b&ei=5088&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss Brown, S. L., Nesse, R. M., Vinokur, A. D., & Smith, D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science, 14, 320-327. Choi, J. S. (2004). Evaluation of community planning and life of senior cohousing projects in Northern European countries. European Planning Studies, 12(9), 1189 -1216. ElderSpirit Community 26 Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Day, J. C. (1996). Population Projections of the United States by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1995 to 2050. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, P251130. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Durrett, C. (2005). Senior cohousing: A community approach to independent living. Berkeley, CA: Habitat Press. ElderSpirit Community Brochure (2005). ElderSpirit Community website: www.elderspirit.net. Fromm, D. (1991). Collaborative communities: Cohousing, central living and other forms of new housing with shared facilities, New York: VanNostrand Reinhold. Felton, B. J. & Berry, C. A. (1992). Do the sources of the urban elderly’s social support determine its psychological consequences? Psychology and Aging, 7(1), 89-97. Gans, H. J. (1967). The Levittowners. New York: Vintage. Gironda, M., Lubben, J. E., & Atchison, K. A. (1999). Social networks of elders without children. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 31, 63-84. Green, K. (2006, October 2). Forget golf courses, beaches, and mountains. Wall Street Journal, p. R1, R3. Greenberg, S. (2006). A Profile of Older Americans: 2006. Washington, DC: Administration on Aging (AOA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Homans, G. (1968). Social behavior - its elementary forms. London: Routledge. Horelli, L., & Vepsa, K. (1994). In search of supportive structures for everyday life. In I. ElderSpirit Community 27 Altman & A. Churman (Eds.) Women and the Environment, Vol. 13. New York, NY: Plenum Press. Jason, L. A. & Kobayashi, R. B. (1995). Community building: Our next frontier. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 15, 3, 195-208. Johnson, C. L., & Barer, B. M. (1990). Families and networks among older inner-city blacks. The Gerontologist, 30, 726-733. Jordan-March, M. & Harden, J. T. (2005). Fictive kin: Friends as family supporting older adults as they age. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 31, 24-31. Lawrence, A. & Schiller-Schigelone, A. R. (2002). Reciprocity beyond dyadic relationships: aging-related communal coping. Research on Aging, 24, 684-704. Leder, D. (1996). Spiritual community in later life: A modest proposal. Journal of Aging Studies, 10,103-116. McCamant, K., & Durrett, C. (1994). CoHousing: A contemporary approach to housing ourselves. Berkeley, CA: Habitat Press. Marcus, C. & Dovey, K. (1991). Cohousing – an option for the 1990’s. Progressive Architecture, 6, 112-113. Meltzer, G. (2005). Sustainable community: Learning From the cohousing model. Victoria, BC, Canada: Trafford. National Center for Health Statistics. (2005). Birth Rates and Fertility Rates. Retrieved May 27, 2007, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statab/t001x01.pdf. National Institute on Aging. (2007). Growing Older in America: The Health and Retirement Study. NIH Publication No. 07-57-57. Washington, DC: U.S. Health and Human Services. ElderSpirit Community 28 Nussbaum, P. D. (Ed.) (1997). Handbook of neuropsychology and aging. New York, NY: Plenum Press. Perrigan, D. (2006, December 10). Houses united. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 30, 2008 from http://www.sfgate.com/cgibin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2006/12/10/REG7LMSDS61.DTL . Pretty, J., & Ward, H. (2001). Social capital and the environment. World Development, 29, 209227. Scanzoni, J. (2000). Designing families: The search for self and community in the information age. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. U.S. Census Bureau. (2006). American FactFinder Data Set 2006 American Community Survey. Retrieved March 2, 2008 from http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/STTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0103&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_ Williams, J. (2005). Sun, surf and sustainable housing – cohousing, the California experience. International Planning Studies, 10, 145-177. ElderSpirit Community 29 Table 1. Age Ranges of ESC Charter Residents Age Percentage Number 60-64 21.88 7 65-69 34.38 11 70-74 15.63 6 75-79 15.63 4 80-84 12.50 4 Total 32 Table 2. Likelihood of ESC Residents Asking Family and Friends for Help Children Very likely Somewhat likely Not at all likely N/A. no answer Number (%) Number (%) Number (%) Number (%) 11 (34.38) 6 (18.75) 6 (18.75) 9 (28.13) Brothers/sisters 5 (15.63) 7 (21.88) 12 (37.50) 8 (25.00) Friends in ESC 26 (81.25) 5 (15.63) 1 (03.13) 0 (00.00) Friends outside 8 (25.00) 13 (40.63) 8 (25.00) 3 (09.38) ESC ElderSpirit Community 30 Table 3. Chronic Health Conditions Among ESC Residents Condition Number reporting condition Number taking medications Number (%) for condition Number (%) Arthritis 16 (51.61) 5 (16.13) Cancer 7 (22.58) 2 (06.45) Diabetes 1 (03.23) 1 (03.23) Heart disease 6 (19.35) 6 (19.35) Hypertension 16 (51.61) 15 (48.39) Note: one did not respond, n = 31 Table 4. Self-Reported Physical and Mental Health of ESC Residents Rating of Health Physical Health Mental Health Number (%) Number (%) Excellent 5 (16.13) 10 (32.26) Very good 13 (41.94) 11 (35.48) Good 8 (25.80) 9 (29.03) Fair 5 (16.13) 1 (03.23) Poor 0 (00.00) 0 (00.00) 31 31 TOTAL Note: one did not respond, n = 31 ElderSpirit Community 31 Table 5. ESC Residents’ Rating of Physical and Mental Health, Compared to One Year Ago Health Compared to a Year Ago Improved About the same Worse than a year ago TOTAL Note: one did not respond, n = 31 Physical Health Mental Health Number (%) Number (%) 5 (16.13) 8 (25.80) 22 (70.97) 22 (70.97) 4 (12.90) 1 (03.23) 31 31 ElderSpirit Community 32 Table 6. ESC Residents’ Reasons for Decision to Move to ElderSpirit Community Reason Mean Score Number Who Chose as Most Important (%) Sense of community 4.69 12 (41.38) Mutual support 4.58 6 (20.69) Simplified lifestyle 4.35 2 (06.90) Spiritual component 4.22 5 (17.24) Cost 3.71 1 (03.44) Location 3.66 1 (03.44) Something new 3.61 2 (06.90) Live with peers 3.55 0 (00.00) Climate 3.00 0 (00.00) Friends living there 2.48 0 (00.00) TOTAL 29 Notes: 3 did not respond, n = 29 Scale: 1 = “Not important at all” to 5 = “Extremely important” ElderSpirit Community (www.elderspirit.net) Figure 1: ElderSpirit Community: Conceptual Model of Late Life Spirituality 33 ElderSpirit Community 34 Disagree Neutral Agree ElderSpirit Community is the name chosen by a group of older adults committed to spiritual growth, caring for one another, respect for the earth, and service to the larger community. ElderSpirit Community is planning their first cohousing neighborhood in Abingdon, Virginia. This questionnaire is designed to help you decide if the ElderSpirit Community (ESC) might be a “good fit” for you and your interests. Read the following statements and note whether you agree or disagree. I respect other spiritual paths and do not hold mine as the only one. I have or would like to have a regular spiritual practice. I try to be as physically active as my health allows. I am interested in learning new things. I value a sense of community with others. I would like to participate in some group activities. I am willing to give some time to ESC work and responsibilities. I have a history of volunteer work and might like to continue. I would like to give and receive caring support as I age. I value the environment and act accordingly (recycling, etc.). I would like to further develop my gifts and talents and encourage others to develop theirs. I am open to change. I appreciate diversity in a community. I am willing to face the mysteries of aging and death. If you agree with most or all of these statements, you might be a good fit for membership in the ElderSpirit Community. For more information about ElderSpirit Community, or their co-housing neighborhood, please contact us at: ElderSpirit Community P.O. Box 665 Abingdon, Virginia 24212 (276) 628-8908 info@elderspirit.net Goodness of Fit, Approved by FOCIS Board, 12/20/01 © FOCIS (www.elderspirit.net) Figure 2: ElderSpirit Community “Goodness of Fit” Questionnaire