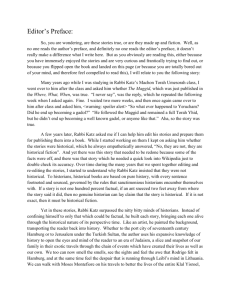

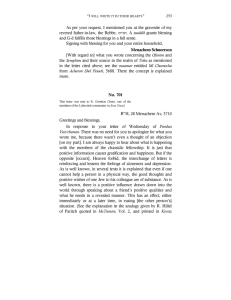

The First Tzaddik of Hasidism

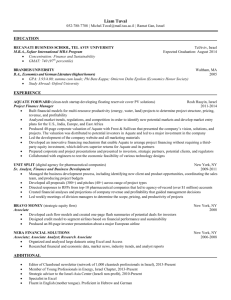

advertisement