history of life insurance - Continuing Education Insurance School of

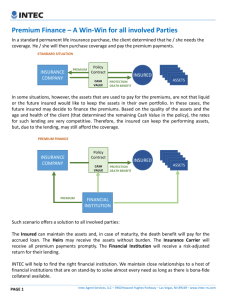

advertisement