The Civil Rights Era

advertisement

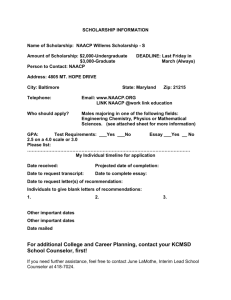

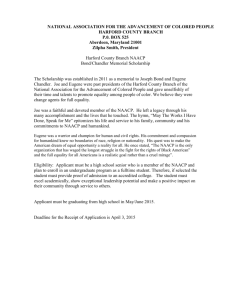

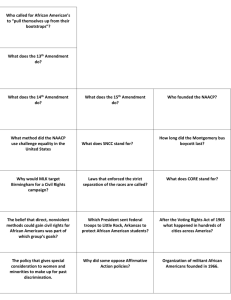

The Civil Rights Era Part 1: Desegregation | Civil Rights in the Arena and on the Stage Part 2 The post-war era marked a period of unprecedented energy against the second class citizenship accorded to African Americans in many parts of the nation. Resistance to racial segregation and discrimination with strategies such as civil disobedience, nonviolent resistance, marches, protests, boycotts, "freedom rides," and rallies received national attention as newspaper, radio, and television reporters and cameramen documented the struggle to end racial inequality. There were also continuing efforts to legally challenge segregation through the courts. Success crowned these efforts: the Brown decision in 1954, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act in 1965 helped bring about the demise of the entangling web of legislation that bound blacks to second class citizenship. One hundred years after the Civil War, blacks and their white allies still pursued the battle for equal rights in every area of American life. While there is more to achieve in ending discrimination, major milestones in civil rights laws are on the books for the purpose of regulating equal access to public accommodations, equal justice before the law, and equal employment, education, and housing opportunities. African Americans have had unprecedented openings in many fields of learning and in the arts. The black struggle for civil rights also inspired other liberation and rights movements, including those of Native Americans, Latinos, and women, and African Americans have lent their support to liberation struggles in Africa. Few other institutions can present the African American mosaic of life and culture as completely as the Library of Congress. The Library's photographs, film footage, newspapers, magazines, manuscripts, and music holdings chronicle this period better than any other collection in existence. In addition to the NAACP and NUL papers, the Library also holds papers of civil rights activists such as Thurgood Marshall, Roy Wilkins, Patricia Roberts Harris, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Mary Church Terrell, Robert Terrell, Nannie Helen Burroughs, and others. Although the quest may not be fully realized, the Library's collections document the relentless and significant process of pursuing full equality. Desegregation President Harry Truman Wipes Out Military Segregation Press release for Executive Order No. 9981, establishing the President's Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Forces. July 26, 1948. Typescript document. NAACP Collection, Manuscript Division. (9-1) Courtesy of NAACP On July 26, 1948, President Harry Truman issued two executive orders. One instituted fair employment practices in the civilian agencies of the federal government; the other provided for "equality of treatment and opportunity in the armed forces without regard to race, color, religion,or national origin." "By Executive Order-President Truman Wipes Out Segregation in Armed Forces." Chicago Defender, July 31, 1948. Copyprint from microfilm. Serial and Government Publications Division. (9-2) Courtesy of the Chicago Daily Defender, Chicago, Illinois. This was a major victory for civil rights advocates in the quest for full citizenship. Land Where Our Fathers Died Oliver W. Harrington (1912-1995) knew he wanted to become a cartoonist during grade school, when drawing caricatures made him feel better about disturbing situations. Harrington received a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Yale University. In 1951, he left the United States, but continued to provide cartoon strips for American newspapers. His images address the social and political injustices of capitalism and racism. Harrington's Dark Laughter strip first appeared in The Amsterdam News in May 1935. Oliver W. Harrington. Dark Laughter. "My Daddy said they didn't seem to mind servin' him on the Anzio beach head. . ." Published in the Pittsburgh Courier, April 2, 1960. Crayon, ink, blue pencil, and pencil on paper. Prints and Photographs Division. (9-28) Courtesy of Dr. Helma Harrington Psychological Effects of Racism Kenneth B. Clark. The Genesis of Racial Identification and Preferences in Negro Children, 1940. K. B. Clark Papers, Manuscript Division. (9-15) In the "doll test," popularized by social psychologists Kenneth Bancroft Clark and his wife, Mamie Phipps Clark, children were given a black doll and a white doll and asked which one they preferred. Most black children preferred the white doll, to which they also attributed the most positive characteristics. During court trials relating to segregated schools, the NAACP and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund enlisted Kenneth Clark's services as an expert witness on the detrimental effects of racial exclusion and discrimination. The Defense Fund lawyers also submitted a report that explained the test results to the Supreme Court as evidence in the Brown v. Board of Education case. In a unanimous ruling in 1954, the court found that separate schools were inherently unequal and specifically cited the Clark report. Thurgood Marshall on "Saving the Race" Thurgood Marshall was the first African American to serve on the U. S. Supreme Court. His legal career began with the NAACP. Many of the NAACP's records reveal Marshall's grueling traveling and meeting schedule, as well as his acute sense of humor, even in the face of threats from whites and distrust by African Americans. After the inauspicious beginning of a case challenging the Texas primary, Marshall wrote this memo. Thurgood Marshall to the NAACP, Tuskegee Institute, Research Department. November 17, 1941. NAACP Collection, Manuscript Division. (8-16) Courtesy of the NAACP Brown Decision--Separate Is Inherently Illegal George E.C. Hayes, Thurgood Marshall, and James Nabrit, congratulating each other, following Supreme Court decision declaring segregation unconstitutional, 1954. Copyprint. New York World-Telegram and Sun Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62111236 (9-11) Courtesy of AP/Wide World Photos. Beginning in 1950, the NAACP and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund attorneys worked on a school desegregation case originating in Charleston, S.C. In 1952 the case came before the U.S. Supreme Court, whose members decided to hear it with cases from Delaware, Virginia, Kansas, and the District of Columbia under the collective title Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. Thurgood Marshall and other NAACP lawyers argued the case and won. Brown marked a landmark victory in the fight for full citizenship, offering hope that the system of segregation was not unassailable. Daisy Bates and The Little Rock Nine Daisy Bates to Roy Wilkins, December 17, 1957, on the treatment of the Little Rock Nine. Holograph letter. NAACP Collection, Manuscript Division. (9-18a) Arkansasborn Daisy Bates worked as a crusading newspaper ownerjournalist, becoming president of the Arkansas NAACP. After the 1954 Brown schooldesegregation decision, Little Rock school board officials decided to begin desegregation of Central High School in September 1957. The Little Rock Nine, ca 195760. Copyprint. NAACP Collection, Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction Number: LCUSZ62-119154 (9-18b) Courtesy of the NAACP Arkansas governor Orval Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to preserve order, a euphemism for keeping the nine prospective African American students out. However, on September 25, 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and deployed paratroopers to carry out the desegregation orders of the federal courts. Bates supported the students throughout the year and with them received the NAACP's Spingarn Medal in 1958. The Montgomery Bus Boycott When Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white person in Montgomery, Alabama, and was arrested in December 1955, she set off a train of events that generated a momentum the civil rights movement had never before experienced. Local civil rights leaders were hoping for such an opportunity to test the city's segregation laws. Deciding to boycott the buses, the African American community soon formed a new organization to supervise the boycott, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). The young pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., was chosen as the first MIA leader. The boycott, more successful than anyone hoped, led to a 1956 Supreme Court decision banning segregated buses. "5,000 at Meeting Outline Boycott; Bullet Clips Bus." Montgomery, Alabama, Bus Boycott. Montgomery Advertiser, December 6, 1955. Copyprint from microfilm. Serial and Government Publications Division. (9-3) Courtesy of the Montgomery Advertiser. James Meredith and Ole Miss In September 1962, a federal court ordered the University of Mississippi to accept James Meredith, a twenty-eight-year-old Air Force Veteran, much to the consternation of segregationists. Governor Ross Barnett said he would never allow the school to be integrated. After days of violence and rioting by whites, Meredith, accompanied by federal officials, enrolled on October 1, 1962. Because he had earned college credits elsewhere, Meredith graduated the following August without incident. Marion S. Trikosko. James Meredith, Oxford, Mississippi, 1962. Copyprint. New York WorldTelegram and Sun Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction Number: LC-U9-8556-24 (9-8) In 1966 Meredith began a 220-mile "March Against Fear" from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi. He hoped to demonstrate a positive change in the racial climate, but he was shot soon after he commenced the march. Civil rights leaders rallied to the cause and came to continue the march from the point at which Meredith fell. Civil Rights in the Arena and on the Stage Gospel Singer Mahalia Jackson Mahalia Jackson was born in New Orleans in 1911, and from childhood sang in church. She resisted the lure to secular music saying, "When you sing gospel you have a feeling there is a cure for what's wrong. But when you are through with the blues, you've got nothing to rest on." She first sang in church store-fronts, but as her recognition grew, she began giving church concerts, making records, and touring the U.S. and abroad. She also sang on radio and television. Jackson became involved with the civil rights movement at the urging of Martin Luther King, Jr. In this photograph she is singing at the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom at the Lincoln Memorial--a civil rights rally, held on the third anniversary of the Brown decision. Jackson also sang just before King's "I have a Dream" speech during the 1963 March on Washington. Mahalia Jackson at the May 17, 1957, Prayer Pilgrimage of Freedom in Washington, D.C. Silver gelatin print. NAACP Collection, Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction Number: LCUSZC4-6177/LC-USZ62-119977 (9-16) Courtesy of the NAACP Jazz and the Civil Rights Movement Max Roach. Jazz performers responded to the force of the civil rights movement by recording and performing their music. The most ambitious response was the Freedom Now Suite of Max Roach, recorded in August and September 1960, and involving such major performers as Coleman Hawkins, Abbey Lincoln, and Nigerian drummer Olatunji. The Freedom Now Suite was issued on the small label Candid Records rather than on Max Roach's regular label, Mercury. We Insist! Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite. New York: Candid Records, 1960. Record jacket. Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division. (9-6) Courtesy of Candid Production, LTD Two Baseball Greats William C. Green. [Willie Mays, standing, with his arm around Roy Campanella], 1961. Copyprint. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection, Prints and Photographs Division. (9-25) Born in 1921 in Philadelphia, Roy Campanella was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1969. Willie Howard Mays, Jr. ("Say Hey"), born in 1931 in Westfield, Alabama, was inducted ten years later. Both Campanella, who was a catcher with the Brooklyn Dodgers for most of his professional years, and Mays, the third African American player in the 1951 Giants outfield, began their careers in the Negro Baseball Leagues. Although Jackie Robinson was the first black player in the major leagues, these other players also faced difficulties and sometimes even danger from hostile players and fans. Record Breaking Hank Aaron By hitting his 715th home run in 1974, Henry Louis Aaron, born in Alabama in 1934, broke Babe Ruth's famous home run record at the age of 40. Some whites resented an African American taking this coveted record and sent thousands of hate letters and threatened Aaron's life and family as he was nearing the record. Before he retired from the Atlanta Braves, Aaron increased the record to 755 runs and held twelve other major league records, including most at bats, most total bases, and most runs batted in. In 1969 the Atlanta Braves fans named "Hank" Aaron the greatest player ever. In 1982, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.