relativization versus nominalization strategies in chimariko

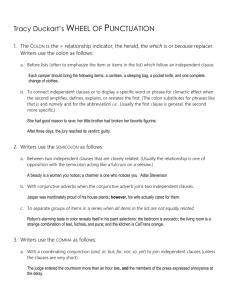

advertisement

11th Annual Workshop on American Indigenous Languages May 22-23, 2008 RELATIVIZATION VERSUS NOMINALIZATION STRATEGIES IN CHIMARIKO Carmen Jany California State University, San Bernardino cjany@csusb.edu 1. Introduction Question: Are relative clauses formally indistinct from clausal nominalization in certain languages? Hypothesis: Chimariko, an extinct language of Northern California, shows no formal distinction between relative clauses and clausal nominalizations Comrie and Thompson (1985:395) ‘… in certain languages clausal nominalization is indistinct from relativization’. Such languages include: Diegueño, Mojave, Luiseño, Wappo, and Quechua (Comrie and Thompson 1985). 1.1 Nominalization (Comrie and Thompson 1985; Givón 1990) Nominalization refers to ‘turning something into a noun’ (Comrie & Thompson) o Derivational process that creates nouns from lexical verbs and adjectives o The resulting nouns become the head noun in a noun phrase Clausal nominalization (Givón): o ‘The process by which a prototypical verbal clause […] is converted into a noun phrase’ o ‘A verbal clause is nominalized most commonly when it occupies a prototypical nominal position (or ‘function) […] within another clause’ o There are structural adjustments (i.e. verb acquires non-finite form, TAM absent, case-marking modified, etc.) Clausal nominalizations are not prototypical nominalizations o They do not involve the derivation of a noun from a verb (the nominalized constituent is an entire clause) o The verb often maintains some of its verbal properties; arguments and adjuncts have the same properties as in a non-nominalized clause 1.2 Relativization (Keenan 1990, Payne 1997, Comrie 1998, Givón 1990) Relative clauses are clauses which restrict the meaning of a noun 1 11th Annual Workshop on American Indigenous Languages May 22-23, 2008 Relative clauses are subordinate clauses embedded – as noun modifiers, inside noun phrases (Givón) Relative clause constructions include four characteristics (Keenan 1985): (1) they are sentence-like (2) they consist of a head noun (present or inferred) and a relative clause (3) they have a total of two predicates (4) they describe or delimit an argument => Chimariko relative clauses include these four characteristics (see 3) => The verb in relative clause constructions occurs with a special suffix -rop marking dependency. But: This suffix could also be interpreted as a clausal nominalizer (see 4) Typological parameters by which relative clauses can be grouped (Payne 1997): (1) Position of the relative clause with respect to the head noun (a) Prenominal (relative clause before head) (b) Postnominal (relative clause after head) (c) Internally headed (head within relative clause) (d) Headless (head inferred) => (c) and (d) found in Chimariko (see 4) (2) Mode of expression of the relativized noun phrase (case recoverability strategy; identifying the role of the referent of the head noun within the relative clause) (3) Which grammatical element can be relativized (relativization hierarchy: subject > direct object > indirect object > oblique) => (2) and (3) and are not examined here given the particular case of Chimariko argument structure which is based on agents and patients and a person hierarchy; however neither the agent-patient distinction nor the person hierarchy are reflected in third persons (see 3) 2. Data Chimariko: Language isolate from Northern California, last spoken in the 1930s Data drawn from the field notes of J. P. Harrington and the notes of George Grekoff: o Harrington collected elicited sentences, vocabulary, and oral narratives from several consultants in the 1920s, leaving 3500 handwritten pages (see Appendix II for sample page) 2 11th Annual Workshop on American Indigenous Languages May 22-23, 2008 o Grekoff examined Harrington’s extensive corpus leaving numerous notes and some analyses 3. Relativization in Chimariko Two relativization strategies: (1) internally headed and (2) headless relative clauses (1) Internally headed relative clauses (Examples 1-5) (Relative clauses in brackets, heads boldfaced, the special verb form underlined) 1. ‘Hopping Game’ (Grekoff 004.008) himantamorop map’un, hiˀamta [h-iman-tamo-rop map’un] h-iˀam-ta 3-fall-DIR-DEP that.one 3-beat-DER ‘Those fellows that went down got beaten.’ 2. Harrington 20-1097 map’un hokoteˀrot yečiˀ ˀimiˀnan [map’un h-oko-teˀ-rot] that.one 3-tattoo-DER-DEP ‘I want to buy that engraved one.’ 3. y-ečiˀ 1SG.A-buy Harrington 20-1103 moˀa pʰuncar huwatkurop pʰaˀyinip [moˀa pʰuncar h-uwa-tku-rop] yesterday woman3-go-DIR-DEP ‘That woman who came yesterday told me.’ ˀi-miˀn-an 1SG-want-ASP pʰaˀyi-nip thus.say-PST 4. Grekoff 020-009 načʰot yak’orop pʰaˀasu, hik’ot [načʰot ya-k’o-rop pʰaˀasu] h-ik’o-t 1PL 1PL-talk-DEP that.kind 3-talk-ASP ‘What we talk, she talked.’ 5. Grekoff 012.014 čʰeˀnew yewurop hačmukčʰa čʰawun [čʰeˀnew y-ewu-rop] hačmukčʰa čʰ-awu-n bread 1SG.A-give-DEP axe 1SG.P-give-ASP ‘For the bread I gave him, he gave me an axe.’ There are no relativizers Heads are all within the relative clause; relative clauses occur with either a head noun (3, 5), or a relative pronoun map’un ‘that one’ (1, 2) or pʰaˀasu ‘that kind’ (4) Relative clauses always precede the main clause 3 11th Annual Workshop on American Indigenous Languages May 22-23, 2008 The heads either precede (2, 3, 5) or follow (1, 4) the dependent predicate Dependent predicate occurs with a special suffix –rop/-rot marking dependency Dependent predicate occurs with pronominal affixes, but lacks tense, aspect or modal suffixes (pronominal and TAM affixes are obligatory in independent clauses) (2) Headless relative clauses (Examples 6-8) 6. Grekoff 012.014 yewuxan ˀahatew hexačilop šičelaˀi y-ewu-xan ˀahatew [h-exači-lop šičela-ˀi] 1SG.A-give-FUT money 3-steal-DEP dog-POSS ‘I’ll give you money for the stealing by my dog.’ 7. Grekoff 020.009 hik’omutarop hitxahta [h-ik’o-muta-rop] h-itxah-ta 3-talk-?-DEP 3-stop-ASP ‘He stopped talking’ (Literally: ‘What he was uttering, he stopped it’) 8. Grekoff 020.009 šitoita hik’orop hek’oˀnačaxat [šito-ita h-ik’o-rop] h-ek’o-ˀna-čaxa-t mother-POSS 3-tell-DEP 3-say-APPL-COMP-ASP ‘She told her mother everything’ (‘What she told her mother, she told her all’) There are no relativizers There are no heads Relative clauses either precede (7, 8) or follow (6) the main clause Dependent predicate occurs with a special suffix –rop/-lop marking dependency Dependent predicate occurs with pronominal affixes, but lacks tense, aspect or modal suffixes Could these constructions be interpreted as clausal nominalizations? 4. Relativization versus Nominalization in Chimariko The predicates in Chimariko relative clauses show properties of nouns and verbs: o Noun-like: (a) lack any tense, aspect, or modal affixes and (b) cannot form clauses by themselves (verbs can form clauses by themselves in Chimariko) o Verb-like: (a) pronominal marking and (b) possibility of taking arguments 4 11th Annual Workshop on American Indigenous Languages May 22-23, 2008 => In clausal nominalization, the verb retains some of its verbal properties: o The Chimariko verb retains its pronominal marking and the possibility of taking arguments => There are structural adjustments in the nominalization process: o Tense/Aspect/Modal suffixes are absent => The nominalized clause occupies a prototypical nominal position (or ‘function) within another clause: o Chimariko is predominantly verb-final and the relative (or nominalized) clauses occur before the main predicate (with the exception of example 6), i.e. in the prototypical nominal position o Nominal function? Clausal nominalization: VP -> NP Relative clause: [[Srel]NP] + VP; Srel restricts meaning of NP Does the Srel restrict the meaning of a head noun? Yes. =>Relative clauses in Chimariko could structurally be interpreted as clausal nominalizations paralleling constructions found in Diegueño and in other languages (see 5), but functionally they are best viewed as relative clauses 4.1 Nominalization in Chimariko There is no construction representing a clausal nominalization in Chimariko (other than the relative clause construction) Lexical nominalizations are common and are formed with the nominalizer –ew: 9. Nominalizations with the nominalizer -ew ama ‘to eat’ => h-am-ew ‘food’ ik’o ‘to talk’ => h-ik’-ew ‘talker’ (‘Woman wanders’) (Harrington 020-1133) => Nominalized verbs and predicates in relative clauses occur with pronominal affixes But: Pronominal affixes could also be interpreted as a possessive affixes (verbal pronominal affixes and nominal possessive affixes are almost identical in shape; difference in first person plural forms and some third person forms) 10a. (same as 4) Grekoff 020-009 [načʰot ya-k’o-rop pʰaˀasu] h-ik’o-t 1PL 1PL-talk-DEP that.kind 3-talk-ASP ‘What we talk, she talked.’ 10b. čʰa-sot 1PL.POSS-eye h-usot 3.POSS-eye 5 11th Annual Workshop on American Indigenous Languages May 22-23, 2008 ‘our eye’ ‘his eye’ => 10a. and 10b. show that the affixes in relative clauses are in fact pronominal and not possessive affixes (as in the nominalized verbs) 4.1 Properties of nouns in Chimariko Nominal stems can take the following types of affixes: o Possessive o Privative (‘without’, ‘…-less’) o Locative o Definitive o Case: instruments –mtu and companions -owa None of these affixes are found on predicates in relative clause constructions, but the verbal suffix marking dependency –rop/-rot/-lop is similar in shape to the nominal suffix marking definiteness: 11. Definite suffix –ot (Harrington 020-1093) šičelot čʰawin, čʰutpai, čʰawin šičel-ot čʰ-awi-n čʰ-utpa-i čʰ-awi-n dog-DEF 1SG.P-afraid-ASP 1SG.P-bite-MOD 1SG.P-afraid-ASP ‘I am afraid of the dog, he might bite, I am afraid’. 12. Definite suffix –op (‘Fugitives at Burnt Ranch’) hek’omatta, hakʰoteˀ č’imarop, xawiyop hakʰoteˀn h-ek’o-ma-tta h-akʰo-teˀ č’imar-op xawiy-op h-akʰo-teˀ-n 3-say-?-DER 3-kill-DER person-DEF Indian-DEF 3-kill-DER-ASP ‘He (the boy) told (it), they killed the boy, the people, the Indians killed him’. Is this indicative of clausal nominalization rather than of a relative clause construction? No. 5. Relativization and Nominalization in Diegueño, Quechua, and Wappo In certain languages clausal nominalization is formally indistinct from relativization (Comrie and Thompson 1985). Three of these languages are examined below. 5.1 Diegueño (Gorbet 1976) 13a. [i:pac ‘wu:w]-puc-c man I.saw-DEM-SUBJ ‘The man I saw sang’ 13b. i:pac ‘wu:w man I.saw ‘I saw the man’ ciyaw sing i:pac-puc-c ciyaw man-DEM-SUBJ sing ‘The man sang’ 6 11th Annual Workshop on American Indigenous Languages 14. ‘nʸa:-c ‘-i:ca-s [puy I-SUBJ I-remember-EMPH ‘I remember that we were there’ May 22-23, 2008 ta-‘-nʸ-way]-pu- ø there PROG-I-be-there-DEM-OBJ => The relativized noun i:pac ‘man’ in 13a. does not change its position or case-marking when compared to 13b. => The verb in the relative clause bears the definiteness and case marking indicated from the function of the relativized noun in the main clause => 13 and 14 show no formal difference; nominalization and relative clauses indistinct Chimariko: There are no relative clauses with case or definiteness markers 5.2 Wappo (Li and Thompson 1978) SOV language with a rich case system (nominative, accusative, dative, etc.) Subjects in subordinate clauses appear in the accusative Three relativization strategies: (a) internal head constructions, (b) pre-posing and (c) post-posing Internal head construction: 15. ˀah [ˀi k’ew-ø I me man-ACC ‘I like the man I saw’ saw nawta] – ø ACC like hak’šeˀ => Relative clause occurs in position in which a simple noun in that function would occur (here O in SOV) => Relative clause marked with the appropriate case marker (here – ø for ACC) => Relative clause clearly subordinate as the subject ˀi ‘I’ occurs in the accusative Chimariko: No case marking on verb 5.3 Quechua (Weber 1983) There is insufficient evidence for distinguishing nouns and adjectives as distinct lexical categories =>There is insufficient evidence that relativized clauses (de-verbal/de-clausal adjectives) and nominalizations (de-verbal/de-clausal nouns) are distinct syntactic classes 7 11th Annual Workshop on American Indigenous Languages May 22-23, 2008 Internally headed relative clause: 16. [marka-man chaya-sha:-chaw] hamashkaa town-GOAL arrive-SUB.1-LOC I.rested ‘I rested in the town to which I arrived’ Nominalized clause: 17. qonqashkaa away-shaa-ta I.forgot go-SUB.1-ACC ‘I forgot that I had gone’ (SUB = substantivizing subordinator, glossed together with pronominal affix) => Relative clause marked with a locative suffix => Relative and nominalized clauses with the same substantivizing subordinators Chimariko: No locative marker on verb Adjectives are morphosyntactically distinct from nouns 6. Summary and Conclusions Diegueño, Wappo, and Quechua all show the following: Relative clauses and nominalized clauses are structurally the same There are no relativizers in relative clauses There are nominal markers on the verb (case, definiteness, etc.) in the relative clauses and the nominalized clauses The relative/nominalized clauses occupy a prototypical nominal position in the main clause But: relative clauses restrict an internal or inferred head Are relative clauses and nominalized clauses structurally the same in Chimariko? Like in Diegueño, Wappo, and Quechua: o There are no relativizers in relative clauses o Relative clauses occupy prototypical nominal positions in main clauses Unlike in Diegueño, Wappo, and Quechua: o No nominal marker (case, definiteness, etc.) on verbs in relative clauses The suffix marking dependency –rop/-rot/-lop could be interpreted as a clausal nominalizer (similar to Quechua), but semantically the constructions found in Chimariko represent relative clauses, because they are restrictive Possible further investigations: Search for relativized instruments or companions (where case marking occurs) Search for negative relative clauses (clausal vs. constituent negation) 8 11th Annual Workshop on American Indigenous Languages May 22-23, 2008 7. Bibliography Comrie, Bernard. 1998. ‘Rethinking the Typology of Relative Clauses’. Language Design 1: 59-86. Comrie, Bernard and Sandra A. Thompson. 1985. ‘Lexical Nominalization’. In: Timothy Shopen ed. Language Typology and Syntactic Description, Vol. III: Grammatical Categories and the Lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 349-398. Givón, T. 1990. Syntax: A Functional-Typological Introduction, Vol. II. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Gorbet, Larry Paul. 1976. A Grammar of Diegueño. New York: Garland. Grekoff, George. 1950-1999. Unpublished notes on various topics. Survey of California and other Indian Languages. University of California, Berkeley. Harrington, John Peabody. 1921-1928. Fieldnotes. Microfilm reels: Northern California 020-024. Jany, Carmen. To appear. Chimariko Grammar: Areal and Typological Perspective. UC Publications in Linguistics. University of California Press. Keenan, Edward. 1985. ‘Relative Clauses’. In: Timothy Shopen ed. Language Typology and Syntactic Description, Vol. II: Complex Constructions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 141-170. Li, Charles N. and Sandra A Thompson. 1978. ‘Relativization Strategies in Wappo’. Berkeley Linguistics Society 4: 116-113. Payne, Thomas E. 1997. Describing Morphosyntax: A Guide for Field Linguists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Weber, David John. 1983. Relativization and Nominalized Clauses in Huallaga (Huanuco) Quechua. UC Publication in Linguistics, Vol. 103. University of California Press. 9 11th Annual Workshop on American Indigenous Languages May 22-23, 2008 Appendix I: Sources for narratives used in the examples Narrative Fugitives at Burnt Ranch Dailey Chased by the Bull Hopping Game Crawfish Source Harrington 021-00071 Grekoff 004.0082 Grekoff 004.008 Grekoff 004.008 LIST OF GLOSSES A Agent ASP Aspect DEP Dependent DER Derivational DIR Directional FUT Future MOD Modal NEG Negative OP Discourse-pragmatic marker P PTCP PST PL POSS PROG Q SG TERM Patient Participle Past tense Plural Possessive Progressive Interrogative Singular Terminative Appendix II: Harrington Sample Page These numbers refer to the microfilm reels with Harrington’s data. The first three digits indicate the microfilm reel and the following number represents the frame number on the reel. The reels are numbered 020-024 of the Northern California collection. The number of frames on one reel varies. 2 The Grekoff Collection is housed at the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages at the University of California at Berkeley. 1 10