Chapter Summary

advertisement

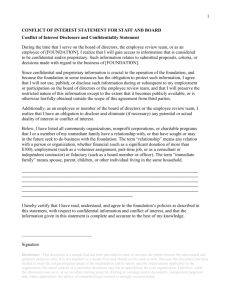

Chapter 6 Duties of Directors & Other Officers Chapter Summary 1 GENERAL LAW DUTIES OF DIRECTORS These duties arise at common law (negligence, contract) and in equity (fiduciary duties). A fiduciary relationship exists where a person holds a position of trust in relation to another person who, due to the circumstances, is vulnerable to misuse of power on the part of the fiduciary. 1.1 Common law duty to exercise reasonable skill and care Breach of this duty is negligence. The defence of contributory negligence may be available. The standard of care expected of each director will vary depending on their particular skills, the size of the company and nature of the company’s business. 1.2 Common law duty of directors to comply with their contract with the company Directors have a duty under contract law to satisfy the obligations in their contract with the company. 1.3 Calculation of damages: the relationship between contract and tort General principles in relation to damages: A person who has suffered loss should be put into the same position they would have been if the contract had been performed properly or the tort had not been committed. The basis of the principle is that the injured party should be compensated for their loss. Consequently, the injured person cannot recover more than their loss. At common law, contributory negligence is a complete defence. Throughout Australia the common law defence of contributory negligence has been replaced by various statutory schemes of apportionment. In CIRCLE PETROLEUM (QLD) P/L V GREENSLADE [1998] QSC 172; (1998) 16 ACLC 1,577, the same facts led to a finding of breach of contract and negligence. The court conluded that, in this case, calculation of damages for the defendant’s negligence and the defendant’s breach of contract would be the same. This is not always the case. In ASTLEY V AUSTRUST LTD [1999] HCA 6; (1999) 197 CLR 1; (1999) 161 ALR 155, the High Court of Australia held that a plaintiff could be liable for contributory negligence even when the defendant had contractually agreed to protect the plaintiff from the very loss that the plaintiff actually suffered as a consequence of the breach. Secondly, the court held that the apportionment legislation did not reduce damages payable for breach of contract. It only reduced damages payable for negligence where the plaintiff was found liable for contributory negligence. 1.4 Fiduciary duty to act in good faith This duty is to act in good faith in the best interests of the company. ‘Company’ here refers to the members as a whole, rather than to individual members: PERCIVAL V WRIGHT [1902] 2 CH 421. A contrasting case is BRUNNINGHAUSEN AND ANOTHER V GLAVANICS [1999] NSWCA 199; (1999) 46 NSWLR 538; (1999) 17 ACLC 1247; (1999) 32 ACSR 294, where the court held that because because Brunninghausen was effectively the sole director and majority shareholder, Brunninghausen owed a fiduciary duty to an individual shareholder to act in good faith. 1.5 Fiduciary duty to exercise powers for a proper purpose The directors of a company owe a fiduciary duty to the company to exercise their powers for a proper purpose. An example of this is the case of PERMANENT BUILDING SOCIETY (IN LIQUIDATION) V WHEELER (1994) 11 WAR 187, (1994) 12 ACLC 674; (1994) 14 ACSR 109. Chapter 6 1 1.6 Fiduciary duty to avoid conflicts of interest Directors also owe a fiduciary duty to the company to avoid any actual or potential conflicts of interest that may adversely affect the company. SOUTH AUSTRALIA V MARCUS CLARK [1996] SASC 5499; (1996) 66 SASR 199; (1996) 14 ACLC 1,019, (1996) 19 ACSR 606 is an example of a case where a director who holds more than one directorship holds conflicting duties. 1.7 Fiduciary duty to creditors Directors also owe a fiduciary duty to the company’s creditors not to trade when the company is or is likely to become insolvent: KINSELA V RUSSELL KINSELA PTY LTD (IN LIQ) (1986) 4 ACLC 215. 2 SPECIFIC STATUTORY POWERS OF DIRECTORS 2.1 Management The directors have the authority to exercise all of the powers of the company except any power that either the Corporations Act or the company’s constitution require to be exercised by the members in general meeting: s 198A(2) (replaceable rule). The sole director of a company who is also its sole shareholder may exercise all of the powers of the company except those powers that the Corporations Act or the company’s constitution (if any) require to be exercised by the members in general meeting: s 198E(1). Section 198C(1) (replaceable rule) provides that the company’s directors may give the company’s managing director any of the powers that the directors can validly exercise. The directors may vary or revoke any of the powers given to the managing director under s 198C(1): s 198C(2) (replaceable rule). If a company’s constitution does not otherwise provide, under s 198D(1) the directors may delegate any of their powers, provided that this is recorded in the minutes (section 251A). The delegate must comply with any directions given by the directors: s 198D(2). When a delegate exercises such a power, s 198D(3) provides that it is as if the directors had exercised the power. Ss 198D(2) and (3) are not replaceable rules. Although s 198D(1) is not specified as a replaceable rule, a company’s constitution may modify the section. Directors who delegate power are still responsible for the actions of the delegate under s 190(1) unless the director had reasonable grounds to believe at all times that in exercising the delegated power the delegate would conform with the company’s constitution (if any) and the duties imposed on directors by the Corporations Act and the director believed on reasonable grounds and in good faith and after making proper inquiry if the circumstances indicated the need for inquiry, that the delegate was reliable and competent in relation to the delegated power. 2.2 Negotiable instruments Section 198B(1) (replaceable rule) provides that in a company with two or more directors, any two directors may sign, draw, accept or endorse a negotiable instrument. The sole director of a proprietary company has the same power under s 198B(1). Section 198B(2) (replaceable rule) gives the directors discretion to vary s 198B(1). Section 198E(2) gives similar power to a sole director of a company who is also the sole shareholder. 2.3 Right of access to company books At common law a director has the right of access to company documents while he/she is a director of the company. This right ceases with the directorship and is restricted to the director’s role as a director within the company: SOUTH AUSTRALIA V BARRETT [1995] SASC 5055; (1995) 64 SASR 73; (1995) 13 ACLC 1,369. Section 198F now specifically deals with a director’s (and ex-director’s) right of access to company books for the purposes of a legal proceeding. Copies are allowed: s 198F(3) and this right overrides any claim for legal professional privilege by the company. For s 198F(1) to apply: the director must be a party to the legal proceedings; or the director must be proposing in good faith to bring the legal proceedings; or Chapter 6 2 the director must have reason to believe that legal proceedings will be brought against them. Section 290 specifically deals with a director’s right of access to the company’s financial records. 3 GENERAL STATUTORY DUTIES OF DIRECTORS These are owed by “officers” (defined in section 9) and are in addition to the general law duties above (s 179 & s 185). However, the business judgement rule defence in section 180(2) will apply to both the statutory & common law due care and diligence duty: section 185. The civil statutory obligations of directors in ss 180 to 183 are civil penalty provisions. A person who has contravened a civil penalty provision is liable to pay the Commonwealth up to $200 000: s 1317G(1). The court must first, however, make a declaration of a contravention: s 1317E(1). Following a declaration of contravention, a court may also make a compensation order against the person whereby that person must compensate a company for loss suffered as a consequence of the contravention: s 1317H(1). However, only ASIC can apply to the court for a declaration of contravention or a pecuniary penalty order: s 1317J(1). Once a declaration of contravention has been made by the court, both ASIC and the company may apply for a compensation order: ss 1317J(1) and (2). Proceedings for a declaration of contravention, pecuniary penalty order or a compensation order may be started no later than six years after the contravention: s 1317K. The company may intervene under s 1317J(3) in an application by ASIC for a declaration of contravention, the company itself has no standing to apply to the court for a declaration of a contravention: section 1317J(4). The company itself may commence proceedings against a director for breach of their common law and fiduciary duties. ASIC would not have standing to commence proceedings here. In these circumstances the company seeks compensatory damages from the director. 3.1 Duty of care and diligence (& the business judgment rule) Section 180(1) provides that a director or other officer of a corporation must exercise their powers and discharge their duties with the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise if: (a) they were a director or officer of a corporation in the corporation’s circumstances; and (b) they occupied the office held by, and had the same responsibilities within the corporation as the director or officer. IN RE CITY EQUITABLE FIRE INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED [1925] 1 CH 407 assists in understanding this duty. The business judgment rule will offer directors a safe harbour from personal liability in relation to honest, informed and rational business judgments. An example is ASIC V VINES [2003] NSWSC 1116; (2004) 22 ACLC 37. Section 180(2) is a rebuttable presumption in favour of directors and states that a director or other officer of a corporation who makes a business judgment is taken to meet the requirements of s 180(1), and their equivalent duties at common law and in equity, in respect of the judgment if they: (a) make the judgment in good faith and for a proper purpose; and (b) do not have a material personal interest in the subject matter of the judgment; and (c) inform themselves about the subject matter to the extent they reasonably believe to be appropriate; and (d) rationally believe that the judgment is in the best interests of the corporation. Section 180(2) continues that the director’s or officer’s belief that the judgment is in the best interests of the corporation is a rational one, unless the belief is one that no reasonable person in their position would hold. Section 180(3) states that ‘business judgment’ means any decision to take or not to take in respect of a matter relevant to the business operations of the corporation. The business judgment rule only applies to operational decisions. It only applies to the statutory and general law duties of care and diligence and does not apply to any other statutory or general law duty concerning, for example, good faith or conflict of interest involving misuse of position or information. Failure of a director to satisfy the business judgment rule does not automatically mean that the director has breached s 180(1). Breach of s 180(1) must still be established. Some relevant case examples of how section 180 operates are: ASIC V ADLERS [2002] NSWSC 171; 41 ACSR 72; ASIC V RICH [2003] NSWSC 85. 3.2 Duties of good faith, use of position and use of information Section 181(1) provides that a director or other officer of a corporation must exercise their powers and discharge their duties: Chapter 6 3 (a) in good faith in the best interests of the corporation; and (b) for a proper purpose. ‘Good faith’ is not defined, but the following cases have discussed the meaning of the section: CHEW V THE QUEEN (1991) 4 WAR 21; (1990-1991) 5 ACSR 473; ASIC V ADLER [2002] NSWSC 171; (2002) 168 FLR 253; (2002) 20 ACLC 576; (2002) 41 ACSR 72; ADLER V ASIC; WILLIAMS V ASIC [2003] NSWCA 131; (2003) 21 ACLC 1,810. 3.3 Use of position Section 182(1) provides that a director, other officer or employee of a corporation must not improperly use their position to: (a) gain an advantage for themselves or someone else; or (b) cause detriment to the corporation. Section 182(2) provides that a person who is ‘involved in a contravention’ of s 182(1) contravenes the section. The duty not to improperly use their position also applies to an employee of the corporation. An objective approach is also to be taken in the application of s 182: ASIC V ADLER [2002] NSWSC 171. 3.4 Use of information Section 183(1) provides that a person who obtains information because they are, or have been, a director or other officer or employee of a corporation must not improperly use the information to: (a) gain an advantage for themselves or for someone else; or (b) cause detriment to the corporation. Section 183(2) provides that a person who is ‘involved in a contravention’ of s 183(1) contravenes the section. An objective approach should be used in the application of s 183. 3.5 Criminal Liability A breach of s 181(1), 182 or 183 will be an offence if the conduct is dishonest or recklessly: s 184. 3.6 Directors of wholly owned subsidiaries Section 187 provides that a director of a corporation that is a wholly owned subsidiary of a body corporate is to be taken to act in good faith in the best interests of the subsidiary if: (a) the constitution of the subsidiary expressly authorises the director to act in the best interests of the holding company; and (b) the director acts in good faith in the best interests of the holding company; and (c) the subsidiary is not insolvent at the time the director acts and does not become insolvent because of the director’s act. 3.7 Reliance on information and advice Section 189 provides that if: (a) a director relies on information, or professional or expert advice, given or prepared by: (i) an employee of the corporation whom the director believes on reasonable grounds to be reliable and competent in relation to the matters concerned; or (ii) a professional adviser or expert in relation to matters that the director believes on reasonable grounds to be within the person’s professional or expert competence; or (iii)another director or officer in relation to matters within the director’s or officer’s authority; or (iv) a committee of directors on which the director did not serve in relation to matters within the committee’s authority; and (b) the reliance was made: (i) in good faith; and (ii) after making an independent assessment of the information or advice, having regard to the director’s knowledge of the corporation and the complexity of the structure of its operations; and Chapter 6 4 (c) the reasonableness of the director’s reliance on the information or advice arises in proceedings brought to determine whether a director has performed a duty under this Part or an equivalent general law duty; the director’s reliance on the information or advice is taken to be reasonable unless the contrary is proved. Section 189 deals with the directors of a company, not other officers or employees. It only applies where the reasonableness of a director’s reliance arises in legal proceedings which have been commenced to determine whether a director has carried out a general statutory duty or an equivalent general law duty. Third, s 189 creates a rebuttable presumption in favour of a director if the elements of the section are satisfied. 3.8 Duty to prevent insolvent trading Section 588G(1) applies if: (a) a person is a director of a company at the time when the company incurs a debt; and (b) the company is insolvent at the time it incurs the debt or becomes insolvent by incurring the debt; and (c) at the time of incurring the debt there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that the company is insolvent or would become insolvent because of the debt or because of other debts incurred at the time. The duty may be breached in two ways. First, a breach occurs if, at the time of incurring the debt, a director was aware that there were reasonable grounds for suspecting the company was insolvent: s 588G(1). Second, a breach occurs if a reasonable person in a similar position in another company in the same circumstances would be aware that there were reasonable grounds for suspecting that the company was insolvent: s 588G(2) (civil penalty provision). A director commits a ‘debt offence’ under s 588G(3) if the director acted dishonestly and suspected at the time of the debt that the company was insolvent. Both liquidators and creditors may recover from a director losses suffered as a consequence of insolvent trading: ss 588M(2) and (3). Directors have a defence in relation to their duty to prevent insolvent trading if they can prove that at the time the debt was incurred they had reasonable grounds to expect that the company was solvent and would remain solvent: s 588H(2). It is also a defence for a director to prove that at the time the debt was incurred they had reasonable grounds to rely upon information regarding solvency supplied by a competent and reliable person: s 588H(3). A court may order a director who has breached their duty to prevent insolvent trading to compensate creditors who have suffered loss as a consequence: s 588J(1). This is in addition to any pecuniary penalty order under s 1317G or an order disqualifying a person from managing a corporation under s 206C. MORLEY V STATEWIDE TOBACCO SERVICES LTD (1992) 10 ACLC 1233 and METROPOLITAN FIRE SYSTEMS PTY LTD V MILLER (1997) 23 ACSR 699 are examples of cases where these sections were applicable. 3.9 Material personal interests Directors of a company must disclose any material personal interest to the other directors: s 191(1) (strict liability offence, but a contravention of s 191 does not affect the validity of any transaction, agreement or resolution). Directors of proprietary companies do not have to give notice if the other directors are aware of the nature and extent of the interest: s 191(2)(b). Directors who have a material personal interest in the affairs of the company may give standing notice of their interest: s 192. Sections 191 and 192 operate in addition to laws regarding conflict of interest: s 193. It is a replaceable rule that a director of a proprietary company may vote on a matter related to their material personal interest if they have disclosed the interest under s 191: s 194. However, a director of a public company may only be present and vote on a matter related to their material personal interest if the directors who do not have any material personal interest in the matter pass a resolution allowing the director to be present and vote: ss 195(1) and (2). ASIC may also make an order that the director is entitled to be present and to vote: s 196. Chapter 6 5