DISNEY CONCERT HALL

advertisement

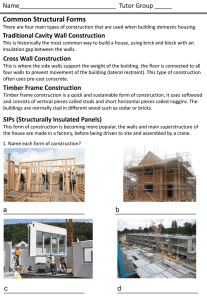

DISNEY CONCERT HALL Monster Wood Ceiling Crowns City of Angels’ Music Heaven (8/11/2003 Issue) High praise for theater’s natural acoustics is music to the ears of the building team By Nadine M. Post On June 30, the Los Angeles Philharmonic first took to the stage of the new, $274-million Walt Disney Concert Hall and played Mozart, Beethoven and Stravinsky to a very select group. The "house" was filled with anticipation, though only 20 of the 2,273 seats were occupied. The audience, composed mostly of those charged with creating the "world’s greatest concert hall," was on tenterhooks. After years of trials and tribulations associated with rendering architect Frank Gehry’s extravagantly sculptural and description-defying forms, the hour of judgment had arrived. "This place can be as beautiful as it is [but] if it doesn’t sound right, it’s a failure," says Jim Yowan, project director for the local office of M.A. Mortenson Co., the general contractor-construction manager. With its percussive, edgy and asymmetrical exterior wrapping a curvaceous and symmetrical wood-lined theater, the 293,000-sq-ft concert hall had about as many learning curves as geometric ones. It was "a long birth," says Terry Bell, partner-in-charge of contract administration for the local Gehry Partners. The job’s supreme challenge was the theater itself, a 238 x 152-ft-wide warped "box," with flared walls up to 130 ft tall, and a flattened-V roofline. It was quite a feat to "get everything in the right place while still making [the theater] look perfect and be acoustically pure," says Yowan. It didn’t take long for the jury to render a sound verdict at the first orchestra session. After a few minutes of the Jupiter Symphony, "I could tell this was a great hall," says cellist Barry Gold, one of three orchestra representatives on the WDCH committee. CENTER STAGE Dazzling Disney Concert Hall grabs spotlight in Impressed with how softly the orchestra could play without sacrificing quality, Gold talks about the sound’s "immediacy and clarity." He isn’t alone in his enthusiasm. Players have called the hall "fantastic," "already a miracle," "magnificent" and "wonderful." Conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen is pleased, Gehry is "thrilled," and the acoustician is "happy." The acoustics will not be altered as a result of the orchestra’s tuning sessions, says Yasuhisa Toyota, director and U.S. representative in the Santa Monica, Calif., office of Nagata Acoustics Inc. downtown Los Angeles. The praise is music to the ears of the beleaguered building team, no REFLECTIONS Simulation shows sound waves reflecting once strangers to unsettling words related to (red), twice (yellow), three times (green). (Graphic courtesy of Nagata the difficult job (ENR 4/8/02 p. 24). Acoustics Inc.) Though no claims or lawsuits have been filed, unconfirmed reports indicate outstanding changes equal 10 to 12% of the roughly $200-million construction cost. Edward J. Burnell, president of WDCH Inc., the job’s development manager, declines to comment on the amount still unresolved, saying only that the project’s "substantial" contingency fund is "gone." The long haul officially began in December 1999 and ended on time April 27, the substantial completion date, says Yowan. It was quite a feat to "get everything in the right place while still making the hall look perfect and be acoustically pure," he says. Success hinged on learning to "play" the project’s digital master "score"–the three-dimensional model created by "composer" Gehry. That daunting task was made worse by plentiful leanings, curves, twists and turns. All but one of the major players, including Mortenson, started out as neophytes on CATIA, the high-end CAD system Gehry uses. The job required "a leap of faith," says Joe Patterson, vice president of Columbia Showcase & Cabinet Co., Sun Valley, Calif. The millwork contractor had a $9.5-million contract to supply the theater’s Douglas fir paneling. SOUND TRIO Acoustician Toyota (l.), orchestra conductor Salonen, architect Gehry, in hall. (Photo courtesy of Marhew Photographic Services) Patterson, now confident in the CAD tool, and others agree the job would have been impossible without CATIA. Joseph P. Riley, project manager-estimator for wall and ceiling contractor Martin Bros./Marcowall Inc., Gardena, Calif., is another CATIA convert. Martin Bros. had a $17-million contract that ballooned to $25 million and included 404,736 sq ft of metal stud framing. The modified theater-in-the-round or "vineyard" seating for the Los Angeles County building, ordered by the main tenant–the orchestra–introduced an acoustical design adventure. "Good natural acoustics are more difficult to achieve" in a vineyard hall than in a tried-and-true, "shoebox" hall, says Toyota. But the team "wanted to look toward the future by breaking with the shoebox," he adds. On the plus side, vineyard seating is more intimate and engaging because it brings the audience closer to the players. On the minus side, it eliminates three proximal stage walls that reflect music toward the audience. The vineyard also needs space for seating rows to the sides and rear of the stage. That means a wider hall, with side walls farther apart than is optimal. Nagata had to contend with still another design element–wood paneling– good for "psycho" but not aural acoustics. Plaster, which has greater mass, is the preferred surface material. Even with a vineyard hall under his belt, Toyota had his work cut out for him. The acoustician first analyzed the hall as a shoebox and then applied the results to the vineyard. This meant a hung ceiling, freestanding walls lining the hall and numerous wood-panel partitions, roughly the height of seat backs, throughout the audience to "replace" proximal full-height walls. TRICKY LOCATION Curved ceiling panels positioned using lasers. (Photo courtesy of Warren Photography Inc.) The acoustician used computer simulation and the architect’s 1:10 scale model of the interior to develop the acoustical design. After tests on the physical model, the only revision to the room was the addition of partial walls with a slatted surface in risers behind the orchestra. Other theaters have movable walls, ceilings and doors to adjust acoustics, depending on the concert. WDCH’s passive design is simpler but "you have to get it right the first time," says Toyota. In May, the acoustician ran a sound test involving brass and percussion instruments. After that, he spent four days taking readings, using a sound source and microphones. Based on some unexpected echoes, the hall is being tuned with the addition of slatted panels on the side balcony walls. Corner ceilings also are being treated to soften echoes, which were anticipated. The theater’s acoustical envelope (AE) is designed to create sounds of silence equivalent to a recording studio’s ambient noise level (NC-15). By comparison, a conference room is NC-35. (Rendering courtesy of Mortenson) Double-wall construction, separated by a 4-ft cavity, and thick concrete slabs above and below, in addition to isolators and sound locks, keep out helicopter, plane and street traffic noise and structureborne vibrations. The basic sound-isolating partition is complicated by the significant dynamic load created by the walls’ tilts, says Tom Schindler, vice president of Charles M. Salter Associates, San Francisco, the sound isolation consultant. At the stage end, the outboard AE wall, with no buffer from city noise, is made from precast concrete panels rigidly attached to the steel frame behind the stainless steel skin. Elsewhere, the outboard AE wall is made from either multiple layers of drywall or shotcrete on light-gauge metal framing. The inboard wall is shotcrete, with neoprene isolators along the bottom. Background noise in the theater has been measured at NC-10 or less, says Schindler. Helicopters passing by the north window are inaudible, he reports. No millwork could be installed without conditioned air for humidity control. But the conditioned air milestone wasn’t reached until Jan. 15, 2002, because the steel frame took six to eight months longer than expected, says Yowan. To make up time, work was resequenced. A big change was to build the wood ceiling and the woodpanel freestanding walls concurrently. This was accomplished thanks to a "dance-floor" platform that allowed work to proceed safely above and below it. The most intimidating part of the auditorium was its drop ceiling, a basket weave of 8,000 dissimilar, curved shapes. To save time and money, the team switched to a prefabricated, panelized ceiling. "We gave a credit of about $2 million to the owner," says Yowan. The ceiling, hung from steel posts that hang from attic roof trusses, is composed of 82, on average 30 x 12-ft panels. Each 1-in.-thick panel is built up from 1 レ 2-in. moisture-proof, medium-density fiberboard. To that, a 1 レ 2-in. veneer is applied, consisting of 1 レ 64-in. Douglas fir pressed onto fire-rated plywood. Columbia and Martin Bros. produced panels with framing at Columbia’s factory after two mock-ups were made. Columbia cut the shapes using a computer numerically controlled machine that received patterns from the CATIA model. Each framed panel was shipped finished side up on a flatbed truck to the site. There, the truck backed through an opening temporarily left in the building’s exterior wall to a spot under a 50 x 20-ft hole in the dance floor. Once the unwrapped panel was flipped over and hoisted onto the dance floor–the pick points having been set in CATIA–it was set on a monorail-and-cart system running the length of the hall and moved under its final resting place. The track, fastened to the dance floor to evenly displace the weight of the 3 to 5-ton panels, had to be repositioned more than 80 times. It was moved a couple times a day. Using chain pulls, workers then lifted the panel and loosely connected it to attic posts, attached to roof trusses. To establish horizontal panel locations, the team used a laser system instead of using a conventional surveying system that would have required measuring each panel corner from a grid system. Two lasers would be positioned for each panel, one on the stage wall and one on a side wall, in a predetermined location based on the CATIA model. During fabrication, a small depression was made in the wood surface at a predetermined location, also based on CATIA. The intersection of the lasers and the depression would determine the panel’s horizontal location. The elevation coordinate was shot conventionally. The laser system drastically cut down the amount of surveying required. Workers then completed the permanent connection, which required welding and bracing. Special fans and "smoke eaters" were required to allow welding to proceed safely in the overcrowded attic. The entire installation went like clockwork, taking 10 days less than the 115 anticipated, says Yowan. Finally, shotcrete for acoustical density was applied to the panels’ upper surface in six operations. UP TEMPO INSIDE AND OUT Disney Concert Hall, 15 years in development, is a jazzy composition of light, texture, form and–beginning Oct. 23–sound. The wood-paneled theater walls were almost–but not quite–easy by comparison. "Each stud is different, and nothing is straight or normal or at the same elevation," says Riley. Much time was saved on wall and ceiling work when a switch was made to a shotcrete backing with the wood panels serving as forms, instead of plaster walls with wood panels adhered after the fact. Shotcrete take less time to cure than plaster. That meant less interference with work on the moisturesensitive finishes. The shotcrete also minimized unwanted voids between the backup material and the wood panel, much to the pleasure of the acoustician. "Using shotcrete took a couple of months off the schedule," says Riley. Everyone on the team agrees that it took an enormous amount of energy and team effort to construct the concert hall from the bottom up. "It was a challenge for contractors to make money on this project," says Yowan. They may not all have made bundles, but they did get introduced to computer-aided construction, CATIA-style. "We’re providing an education to the industry," says Bell. Gehry’s team, which peaked at 12 at the jobsite, also benefited. "It was very exciting to be out here and the opportunity of a lifetime for young people, for it provided good technical training," says Bell Adds Bell, looking back to the first rehearsal: "It was a very emotional experience. The only thing that will top it is to see the hall filled" at the first concert, Oct. 23. (All other photos by Michael Goodman for ENR)