2007 - Magistrates Cases

advertisement

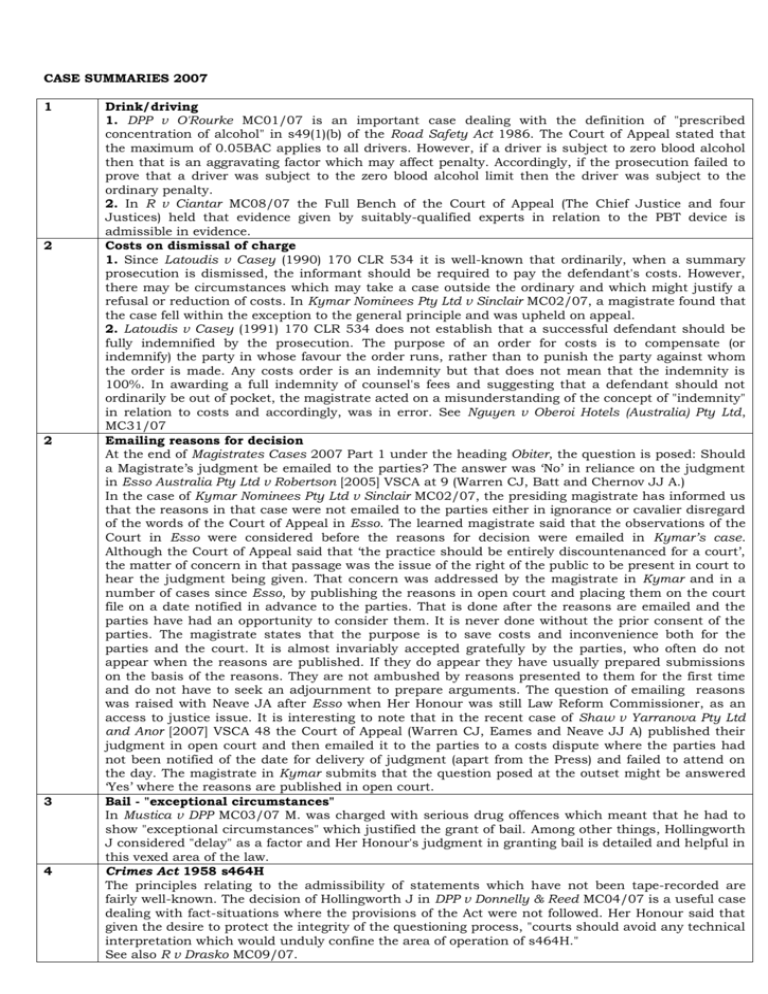

CASE SUMMARIES 2007

1

2

2

3

4

Drink/driving

1. DPP v O'Rourke MC01/07 is an important case dealing with the definition of "prescribed

concentration of alcohol" in s49(1)(b) of the Road Safety Act 1986. The Court of Appeal stated that

the maximum of 0.05BAC applies to all drivers. However, if a driver is subject to zero blood alcohol

then that is an aggravating factor which may affect penalty. Accordingly, if the prosecution failed to

prove that a driver was subject to the zero blood alcohol limit then the driver was subject to the

ordinary penalty.

2. In R v Ciantar MC08/07 the Full Bench of the Court of Appeal (The Chief Justice and four

Justices) held that evidence given by suitably-qualified experts in relation to the PBT device is

admissible in evidence.

Costs on dismissal of charge

1. Since Latoudis v Casey (1990) 170 CLR 534 it is well-known that ordinarily, when a summary

prosecution is dismissed, the informant should be required to pay the defendant's costs. However,

there may be circumstances which may take a case outside the ordinary and which might justify a

refusal or reduction of costs. In Kymar Nominees Pty Ltd v Sinclair MC02/07, a magistrate found that

the case fell within the exception to the general principle and was upheld on appeal.

2. Latoudis v Casey (1991) 170 CLR 534 does not establish that a successful defendant should be

fully indemnified by the prosecution. The purpose of an order for costs is to compensate (or

indemnify) the party in whose favour the order runs, rather than to punish the party against whom

the order is made. Any costs order is an indemnity but that does not mean that the indemnity is

100%. In awarding a full indemnity of counsel's fees and suggesting that a defendant should not

ordinarily be out of pocket, the magistrate acted on a misunderstanding of the concept of "indemnity"

in relation to costs and accordingly, was in error. See Nguyen v Oberoi Hotels (Australia) Pty Ltd,

MC31/07

Emailing reasons for decision

At the end of Magistrates Cases 2007 Part 1 under the heading Obiter, the question is posed: Should

a Magistrate’s judgment be emailed to the parties? The answer was ‘No’ in reliance on the judgment

in Esso Australia Pty Ltd v Robertson [2005] VSCA at 9 (Warren CJ, Batt and Chernov JJ A.)

In the case of Kymar Nominees Pty Ltd v Sinclair MC02/07, the presiding magistrate has informed us

that the reasons in that case were not emailed to the parties either in ignorance or cavalier disregard

of the words of the Court of Appeal in Esso. The learned magistrate said that the observations of the

Court in Esso were considered before the reasons for decision were emailed in Kymar’s case.

Although the Court of Appeal said that ‘the practice should be entirely discountenanced for a court’,

the matter of concern in that passage was the issue of the right of the public to be present in court to

hear the judgment being given. That concern was addressed by the magistrate in Kymar and in a

number of cases since Esso, by publishing the reasons in open court and placing them on the court

file on a date notified in advance to the parties. That is done after the reasons are emailed and the

parties have had an opportunity to consider them. It is never done without the prior consent of the

parties. The magistrate states that the purpose is to save costs and inconvenience both for the

parties and the court. It is almost invariably accepted gratefully by the parties, who often do not

appear when the reasons are published. If they do appear they have usually prepared submissions

on the basis of the reasons. They are not ambushed by reasons presented to them for the first time

and do not have to seek an adjournment to prepare arguments. The question of emailing reasons

was raised with Neave JA after Esso when Her Honour was still Law Reform Commissioner, as an

access to justice issue. It is interesting to note that in the recent case of Shaw v Yarranova Pty Ltd

and Anor [2007] VSCA 48 the Court of Appeal (Warren CJ, Eames and Neave JJ A) published their

judgment in open court and then emailed it to the parties to a costs dispute where the parties had

not been notified of the date for delivery of judgment (apart from the Press) and failed to attend on

the day. The magistrate in Kymar submits that the question posed at the outset might be answered

‘Yes’ where the reasons are published in open court.

Bail - "exceptional circumstances"

In Mustica v DPP MC03/07 M. was charged with serious drug offences which meant that he had to

show "exceptional circumstances" which justified the grant of bail. Among other things, Hollingworth

J considered "delay" as a factor and Her Honour's judgment in granting bail is detailed and helpful in

this vexed area of the law.

Crimes Act 1958 s464H

The principles relating to the admissibility of statements which have not been tape-recorded are

fairly well-known. The decision of Hollingworth J in DPP v Donnelly & Reed MC04/07 is a useful case

dealing with fact-situations where the provisions of the Act were not followed. Her Honour said that

given the desire to protect the integrity of the questioning process, "courts should avoid any technical

interpretation which would unduly confine the area of operation of s464H."

See also R v Drasko MC09/07.

5

6

7

8

9

Costs – Offer of Compromise

In Stipanov v Mier (No 2) NC05/07, Hollingworth J dealt with the question of costs in civil

proceedings generally and in relation to cases where an offer of compromise has been made. Her

Honour held:

1.

Whilst a court has power to order that costs be taxed on a party and party basis, a solicitor

and client basis, an indemnity basis or such other basis as the court may direct, the general rule is

that the court will order costs to be taxed on a party and party basis.

2.

The Rules do not provide for the situation where the plaintiff fails altogether and judgment is

given for the defendant. However, it is well-established in such an event the court may, in the

exercise of its general discretion, award costs to the defendant on a more generous basis than party

and party from the time the offer was served.

3.

The principle in Calderbank v Calderbank [1976] Fam 93; [1975] 3 All ER 333 exposes a

litigant to the risk of a costs order if, taking into account all relevant considerations including the

facts known to the offeree at the time of the offer, the offeree unreasonably ignores a reasonable offer

of settlement, whether made by letter or formal offer of compromise.

4.

The reasonableness of the offer of compromise has to be ascertained on the facts known at

the time of the making of the offer. At the time of the offer, it would have been reasonable for those

advising S. to have concluded that she had strong prospects of establishing negligence and that

damages in excess of $35,000 might be recovered. There is a particular danger in considering issues

of witness credibility through the prism of hindsight.

Richfield Investments v OCBC Ltd [2004] VSC 351; and

Grynberg v Muller [2002] NSWSC 350, applied.

5. In the circumstances, S. did not act unreasonably in rejecting the first offer of compromise.

Accordingly, S. should pay M.s costs on a party/party basis.

Occupational Health & Safety

In Schierholter v County Court of Victoria & Anor MC06/07, the Court of Appeal had no difficulty in

rejecting a submission that the Authority to prosecute was deficient. This argument has cropped up

in other cases and seems like a technical argument that has surely run its course.

Re-examination of Witness

The rule laid down by Harris J in Hatziparadissis v GFC (Manufacturing) Pty Ltd [1978] VR 181 that

in order to compel tender of a document it must be done whilst the witness is still under crossexamination has been overruled. This decision had been doubted and not followed in other

Australian courts. Now the Court of Appeal in R v Vella MC07/07 has said that the court controls the

reception of evidence and there is no time limit on the tender of a document provided the crossexaminer has made it admissible and it is receivable under the ordinary rules.

Evidence – PBT and Breath Analysing Instruments

The Court of Appeal in R v Ciantar MC08/07 considered the admissibility of evidence given in

relation to PBT and breath analyzing instruments and whether the readings obtained from a PBT

device is admissible as evidence of blood/alcohol concentration. The Court held:

1. The provisions of S58 of the Road Safety Act 1986 are facultative. They do not purport to exclude

nor do they have the effect of rendering inadmissible proof aliunde of blood alcohol concentration.

Like any other bodily condition, blood alcohol concentration may be proved by any recognised and

reliable scientific technique. A court may admit results of a test conducted with a scientific

instrument on the basis of evidence from a witness expert in its use. It is sufficient if it is established

that it is a scientifically accepted instrument for its avowed purpose and that the particular

instrument was handled properly and read accurately.

Mehesz v Redman (No 2) (1980) 26 SASR 244, followed.

Porter v Kolodzeij (1962) VR 75, doubted.

2. Where evidence was given by expert witnesses that the PBT is within a class of instrument

generally accepted by experts as accurate for its particular purpose and that if handled properly

produces accurate results and there was evidence to show that the PBT was handled properly and

read accurately by the operator on the relevant occasion, a court was not in error in admitting

evidence of the PBT result.

Tape-recorded interviews

In R v Drasko MC09/07, the Court of Appeal considered the question of the admissibility of a taperecorded interview. In dismissing the appeal against conviction and sentence, the Court held:

1. The statements were made in furtherance of D.s desire to secure benefits under a civil contract of

insurance pursuant to arrangements into which she had voluntarily entered. The duty of disclosure

under a civil contract of insurance in no way restricts the capacity of an individual to speak or

remain silent under the criminal law or interfere with the manner in which the choice may be

exercised. D. can be taken to have been well aware that the insurance company was entitled to

ascertain whether or not she was entitled to benefits before any payment was made and her conduct

on this occasion constituted, on the prosecution case, an integral part of her alleged criminal

enterprise. No question of the making of a statement against penal interest in respect of an earlier

committed crime arose. The evidence was not probative as an admission against interest and

admissible on this basis as an exception to the hearsay rule, but because it was directly relevant to

10

11

the central question in the trial, namely, whether D. had attempted to defraud the company. In any

event, there was nothing whatever to suggest that D.s will may have been overborne or her capacity

to exercise a free choice compromised in any way. In so far as there was an inducement for the

making of the statements, it arose from the applicant’s earlier and continuing desire to secure

benefits under her contract of insurance. Finally, there was no indication that either D. or the private

inquiry agent ever perceived him as "a person in authority", save perhaps to the limited extent that

he could have reported adversely in relation to a civil claim.

2. D. was on any view of the evidence, not "a person in custody". The police officer did nothing more

than secure a voluntarily made statement from D. withdrawing her complaint and setting out her

stated reason for doing so. The police officer engaged in no abuse of power, trickery or subterfuge.

3. Having regard to the fact that the reported 'burglary' did not take place and that none of the

chattels the subject of D.s claim belonged to her or were at the premises when the 'burglary' allegedly

occurred, there was ample evidence before the jury to support the conviction of D.

4. In relation to sentence, whilst D. had no prior convictions, was suffering symptoms of significant

depressive illness and the adverse consequences suffered including loss of her job, it was open to the

judge to state that "insurance contracts are contracts of ultimate good faith and require the

scrupulous honesty of people who deal with insurance companies. Attempted frauds of this nature

must be the subject matter of curial disapproval, and the message must be clear to all people who

are minded to commit offences of this nature that they will not be tolerated." There was no error in

the sentence imposed.

Crown Proceedings Act proceedings – relief against a forfeiture order

In Renate Mokbel v DPP MC10/07, Gillard J dealt with an application by a surety for relief against a

forfeiture of bail order. In dismissing the application, Gillard J held:

1. It is clear from the wording of s6(4) of the Crown Proceedings Act 1958 ('Act') that M. carried the

burden of persuading the Court on the balance of probabilities that it "would be unjust to require her

to pay the amount undertaken to be paid having regard to all the circumstances of the case". The

Court’s jurisdiction extends to varying or rescinding the order if the circumstances justify it. The

question is, would it be unjust to require the applicant to pay the amount undertaken to be paid,

taking into account all the circumstances of the case?

2. First, to be a surety is a serious matter, and suretyship is not to be entered into lightly. Secondly,

the accused person on release is entrusted by the Court to the surety, who has an obligation to

ensure that he/she attends the trial. This requires the surety to take positive steps. It is no answer

for the surety to stand by and do nothing and then state that he or she believed that the accused

would attend his/her trial. By signing an undertaking, the surety guarantees to the Court and the

community that he or she will take steps to ensure the presence of the accused at trial. In one sense,

it is a guarantee, but the legal principles relating to guarantees in commercial law do not apply to the

surety’s obligation.

3. The first question on an application under s6(4) of the Act is to determine whether or not a surety

has fully and properly performed the duties imposed upon him or her by the suretyship. The test is

whether or not the surety has taken all reasonable steps to secure the attendance of the principal

party to the undertaking. The surety must take some positive step. To do nothing would not satisfy

the test.

4. Absent any changed circumstances relating to the financial affairs of the surety after the

undertaking has been executed, the impact upon the surety’s financial position of enforcing the

undertaking is not a matter that should be taken into account. The fact is that on occasions,

accused persons fail to surrender themselves for trial. The possibility of this occurring is not remote.

There is a risk. If the risk materialises, then the undertaking requires the surety to pay the full

amount. That is what the surety agrees to do. It would undermine the system if, having given

thought to entering into the undertaking and swearing an affidavit as to the assets which he or she

has to meet the undertaking, the surety could be relieved from the full obligation and ordered to pay

a lesser amount because of the financial impact.

5. Having regard to the fact that M. did not take all reasonable steps to ensure attendance of the

accused at trial, that there were no new circumstances which should be taken into account in

considering the financial impact, that M. was not a genuine surety and that M. did not disclose her

true financial position, M. failed to persuade the Court that it would be unjust to require her to pay

the amount undertaken to be paid.

6. Factors relevant to the Application. See paras 64-67 of His Honour’s judgment.

Charter of Human Rights

In R v Williams, MC11/07, King J dealt with aspects of the new Charter of Human Rights and

Responsibilities Act 2006 which fully comes into operation on 1 January 2008. This Act applies to

Magistrates' Courts and Her Honour's comments are essential reading for all Magistrates. The

intention of Parliament is for the Courts to become actively involved in the interpretation of the

Charter and Human Rights after 1 January 1908. The rights as declared, at the least in s25 would

be rights that the Court would be bound to take into account in ensuring that a fair trial was

conducted pursuant to s24. Magistrates will be well-advised to familiarise themselves with the

relevant provisions of this Act

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Whether sentence for an offence under the Road Safety Act 1986 makes a person a prohibited

person for the purposes of s3 of the Firearms Act 1996.

In R v Coner MC12/07 the Court of Appeal held:

A conviction and sentence of imprisonment for an offence under the Road Safety Act 1986 does not

make one a prohibited person for the purposes of the Firearms Act 1996 ('Act'). Accordingly, a court

was in error in finding that C. was a prohibited person within the meaning of s3 of the Act and

finding the charge proved.

Duty of Magistrates to give reasons

It has been said time and again that Magistrates have a duty to give reasons for judgment. This is so

that the appeal court can identify the reasoning and the basis upon which the decision was made. In

Insurance Manufacturers of Australia Pty Ltd v Vandermeer MC13/07, after a two-day hearing a

Magistrate gave brief reasons which failed adequately to disclose how he came to his ultimate

conclusion. This meant that the matter had to be sent back for retrial before another Magistrate

which involved a waste of time and costs for all concerned.

Natural Justice

In R v Bennett MC14/07, the Court of Appeal heavily criticised a County Court Judge who failed to

give counsel a copy of a Pre-sentence report and then proceeded to impose a sentence of immediate

imprisonment without giving Counsel an opportunity to make further submissions. The Chief Justice

said such a course was "entirely inappropriate" and Nettle JA said it was "surprising and regrettable

that a judge of the County Court should receive and act upon a pre-sentence report without affording

an opportunity to those to whom it relates to consider it and make submissions upon it."

Deeming provisions of Drugs Act

In R v Tran MC15/07, the Court of Appeal handed down a useful decision which deals with the way

in which the deeming provisions of the Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981 operate.

The phrase "prima facie evidence" is examined along with the elements of "possession".

Unrepresented defendants and natural justice

In Rich v Magistrates’ Court of Victoria and Anor, MC16/07, the question was raised whether there is

a breach of the rules of natural justice if a committal proceeding is conducted with the accused not

legally represented. Maxwell P said that whilst it might be preferable for the accused to be legally

represented, there was no breach of natural justice in proceeding with the accused unrepresented.

His Honour also said that a court has no power to review a decision by Victoria Legal Aid about the

provision or otherwise of funding for a particular case. “Availability of legal aid is not unlimited”, His

Honour stated. Maxwell P endorsed the views of the committing magistrate who said there was a

duty on the court to ensure that an accused person is not obstructed by the authorities in the

preparation of the case.

Suppression orders

The question of making a suppression order was ventilated again in Herald & Weekly Times Pty Ltd v

DPP & Ors, MC17/07. Kaye J said that the court when making the order needs to be satisfied that

the order was “necessary” for one or more of the purposes stipulated in the statutory provisions.

Where a court had “no doubt” in light of information provided by an informer that the circumstances

were exceptional and grave risks existed, it dictated the conclusion that it was necessary to make a

suppression order so as not to endanger the physical safety of the informer.

Matters to be taken into account when making a suppression order

In ABC v D1 & Ors; ex parte The Herald & Weekly Times Ltd MC47/07, Forrest J set out matters

which should be taken into account when a court is considering making a suppression order. In

relation to the making of a pseudonym order, His Honour said: "A court, in determining whether to

make a pseudonym order, is entitled to take into account the individual considerations affecting the

person seeking the order and balance those against the principal rule of open justice in determining

whether the administration of justice warrants the making of the order. Relevant to these individual

considerations is whether there is a real risk of the party or witness suffering psychological harm as

a result of publication of his or her name or the names of other parties. Also relevant is the real risk

of a party not proceeding with an action in the event that he or she or another person is identified."

Service of Taxation Notices

For some reason, the service provisions of the Income Tax Assessment Tax Act 1936 have to be

strictly complied with in relation to the service by the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation of penalty

notices. It has been held that if the DCT wishes to rely on the regulations to effect service, the

Commissioner must strictly comply with the provisions. In DCT v Guastalegname, MC18/07, the

Commissioner sent a penalty notice to the defendant at his address for service. Instead of including

the tax agents company name on the notice, the DCT addressed the notice to the defendant. The

notice obviously came to the attention of the defendant who appeared in court and submitted that

the provisions of service had not been strictly complied with. The magistrate agreed and the charge

was dismissed. Williams J agreed with this conclusion.

Preliminary Breath Test

Where a motorist was pulled over by a police officer standing in the middle of the road holding a

torch and required the motorist to undergo a preliminary breath test, a magistrate was correct in

holding that the requirement was not made at a preliminary breath testing station. In s53(1) of the

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Road Safety Act 1986, there are four separate sets of conditions which allow a police officer to require

a person to undergo a PBT. In Maitland v Swinden, MC19/07, the Court of Appeal upheld the

magistrate’s decision to convict. Redlich JA also said that evidence of compliance with s53 is not an

essential element of the offence under s49(1)(f) and it need not be particularised in the charge. It is

sufficient that there be evidence which enables the court to be satisfied that there has been a lawful

request pursuant to s53(1).

New Facts and Circumstances

The “new facts and circumstances” provisions of the Bail Act 1977 were considered by Curtain J in

O’Reilly v DPP, MC20/07. In that case O’Reilly was charged with serious offences and bail had been

previously refused. In a subsequent application for bail, Curtain J held that the fact that a coaccused has been granted bail is not a new fact or circumstance justifying bail. “Each application for

bail must be decided on its own facts and circumstances”, her Honour said. Also, a judge expressing

remarks at a preliminary hearing, which remarks are at variance with the assessment of the case,

cannot amount to new facts and circumstances.

Assignment of debt: Unjust enrichment

The assignment of debt was discussed in detail by Kaye J in Alma Hill Constructions Pty Ltd v Onal,

MC21/07. In that case, O’s motor vehicle was damaged and later repaired. A third party paid the

repairer for the value of the work done in exchange for an assignment of the debt. O. was later sued

by the third party but no notice of the assignment was given to O. The magistrate, in declining to

follow a decision of the Queensland Court of Appeal (Thomas v National Australia Bank Limited & Ors

[2000] 2 QdR 448), held that the third party could not sue in its own name without prior notice of

the assignment having been given to O. The magistrate also held that there was no unjust

enrichment on O’s part as O and the third party were “strangers” to each other. Kaye J said that the

magistrate should have followed Thomas’ Case. There was no need for the notice of assignment to be

first given to O. In relation to the unjust enrichment point, the magistrate was correct as it could not

be said that O. received any benefit from the third party in circumstances in which he should have

realised that he would be under an obligation to pay for it.

Easement of Way

The question of easement of way was reviewed by the Court of Appeal in Boglari & Anor v Steiner

School and Kindergarten, MC22/07. Damages were claimed in the Magistrates’ Court when the

Boglaris constructed a gate and fence thereby interfering with the rights granted by an easement.

Neave JA discussed the question of the use of easements in detail and held that the magistrate was

not in error in finding that the use of the easement had been interfered with. Also, the magistrate

was not in error in making an order that if the Boglaris did not remove the obstruction, they would

be liable to pay for the costs of removal.

Welfare Fraud Sentencing

The question of sentencing in welfare fraud cases was discussed by the Court of Appeal in R v Berry,

MC23/07. In that case, Berry lodged false documents over a long period of time and obtained the

sum of $56,173.80 to which he was not entitled. He was sentenced in the County Court to 3 years’

imprisonment with 2 years’ immediate custody. In stating that in the circumstances Berry was

correctly sentenced to an actual term of imprisonment, the Court said that the sentence was

manifestly excessive. In lieu, the court imposed a sentence of 2 years and 4 months’ imprisonment to

be released on a recognisance after serving 218 days, that is, the time spent in custody awaiting the

result of the appeal.

Dealing with the case presented by the Prosecution

In Citipower Pty v Leahy, MC24/07, King J reminded magistrates that they should only deal with the

case which has been conducted before them. A magistrate is not permitted to reformulate the

prosecution case because to do so denies the defendant the opportunity of meeting the case

ultimately decided by the magistrate. Such an error is so fundamental that it goes to the root of

whether a proper trial between the parties has been conducted at all.

Adequate reasons for Decision

The decision of King J in Insurance Manufacturers of Australia v Villella, MC25/07 is a timely

reminder that magistrates should be careful about statements they might make during the hearing of

a case. In that case, the magistrate made some ill-judged remarks about the unreliability of hospital

records kept by medical practitioners and medical staff. The magistrate then went on to reject

evidence which had been given by medical practitioners saying that he was not “impressed” by the

evidence given by a general surgical Registrar at a large hospital. King J said that the magistrate did

not give adequate reasons for making his decision and further, that there has been scientific

research in recent years which casts doubt on the ability of judges (or anyone else) to tell truth from

falsehood accurately on the basis of appearances.

Cameras in Court

In R v Williams, MC26/07, King J dealt with an application to film court sentencing proceedings.

This is a useful decision on this point and puts the case for and against filming in court. In R v

Avent, Mr Justice Teague allowed cameras into court to film the sentencing process. However, King J

in Williams’ Case did not follow this decision and gave several cogent reasons why such a course

should not be followed in the case before her Honour.

27

27A

28

29

30

31

Applications to be again licensed

In Robinson v Nixon, MC27/07, Smith J held that when a magistrate is dealing with an application

by a person to be again licensed to drive a motor vehicle, the magistrate has a discretion as to

whether an alcohol interlock condition should be imposed. It would be desirable if the decision to

grant the application be made solely on the basis of the history of the individual since the offence

and whether it would be appropriate to make an order for the licence to be granted independently of

whether there are any devices or techniques which could monitor that individual’s behaviour while

driving with a licence and provide some protection to the community as a result. Approaching the

order for the grant of a licence independently of the consideration of the condition has the effect that

the magistrate will need to be persuaded that the particular applicant has demonstrated that the

risks and problems that existed at the time of the commission of the offence and the conviction have

been sufficiently addressed by the applicant. The question of whether an alcohol interlock condition

should be imposed is a matter to be taken up once the magistrate is satisfied that an order granting

the licence should be made.

Extradition Proceedings

In Berichon v Chief Commissioner, Victoria Police, MC27A/07, Mandie J held that where a magistrate

is dealing with an application for extradition pursuant to s83(8) of the Service and Execution of

Process Act 1992 (Cth) ('Act'), the magistrate is required to make one or other of the orders

contemplated by s83 of the Act. If the magistrate is satisfied that the warrant or a copy of the

warrant produced is not invalid, then the magistrate is required to remand the person on bail to

appear in the place of issue of the warrant or order that that person be taken in custody to that

place. The magistrate has no power to decline to make an extradition order on the ground of abuse of

process and the Supreme Court reviewing such an order has no wider power. The question of abuse

of process is a matter for the courts of the issuing State.

R v Lavelle (1995) 82 A Crim R 187;

Re Dalton (1995) 120 FLR 408; and

Rose v Chief Commissioner of Police MC09/2001; [2000] VSC 281, followed.

Loveridge v Commissioner of Police for South Australia (2004) 89 SASR 72, not followed.

Aggravating Factors in Sentencing

The Court of Appeal in R v Kolicic, MC28/07, restated the principle that in sentencing, defence

conduct is not to be treated as an aggravating factor. It is impermissible to increase what is a proper

sentence for the offence committed, in order to mark the court’s disapproval of the accused’s having

put the issue to proof.

Admissibility of Prior Inconsistent Statement

The question of admissibility of evidence was discussed in detail by Bell J in Engebretson v Bartlett,

MC29/07. Where evidence is put on an untenable basis and rejected, an appeal may be brought if

the evidence is admissible on an alternative basis. Excluding evidence in such circumstances can be

an error of law. One example of that principle is the case of evidence going to an issue being put on

one basis when it is only admissible on another. Accordingly, a magistrate was in error in not

admitting evidence which may have showed that the principal witness for the Prosecution may have

made a prior inconsistent statement.

Overloading and Privacy Principles

In C Cockerill & Sons (Vic) Pty Ltd v County Court of Victoria and Anor, MC30/07, the questions of

overloading and the Privacy Act provisions were considered by Mandie J. The prosecution sought to

prove that a prime mover and the attached semi trailer were overloaded on a number of occasions.

Part of the proof included the production of documents produced by the weighbridge operator. Also,

there was no proof that the defendant was the registered proprietor of the semi-trailer. Mandie J held

that the magistrate was not in error in finding the charges proved. The registration of the attached

semi-trailer was not an element of the offence that needed to be proved. It was sufficient to prove

that the defendant was the registered proprietor of the prime mover. The reference in the chargesheet to the registered number of the prime mover in the context of the language of the charges,

made it clear to the defendant that it was being charged in its capacity as the registered operator of

the specified registered prime mover that formed part of the allegedly overweight combination.

Accordingly, the court was not in error in convicting the defendant of the charges. In relation to the

submission that the documents contravened the provisions of the Privacy Principles, His Honour

held that assuming that the firm contravened the Commonwealth Privacy Act and/or the State

Privacy Act, or a least on the assumption that the informant acted unfairly, having regard to the

disclosure and use of the weighbridge tickets, it was open to the court in the exercise of its discretion

to admit the evidence of the tickets into evidence. In performing the balancing exercise as required by

R v Ireland (1970) 126 CLR 321 and Bunning v Cross (1978) 141 CLR 54, the court was correct in

taking into account that broader questions of high public policy existed in which the unfairness to

the defendant firm was only one factor. The court was right to consider that the defendant was a

body corporate which derived no protection from the privacy legislation, there was no unfairness to

the defendant and there was the strong countervailing consideration of the public importance of road

safety.

Senior Counsel in the Magistrates' Court

32

33

34

More than 40 years ago Starke J in Day v Hunter, unrep, VSC, 31/5/1966 said it would be a very

rare occasion that the costs of senior counsel would be allowed in the Court of Petty Sessions. In

Nguyen v Oberoi Hotels Pty Ltd MC31/07 a magistrate determined that Oberoi Hotels Pty Ltd (OHP/L)

was justified in retaining senior counsel in relation to charges under the Accident Compensation Act

1985 alleging that a worker was summarily dismissed. The magistrate relied on several irrelevant

matters such as hearsay evidence in an email from OHP/L’s General Manager as to the

consequences of OHP/L being convicted of the charges and the necessity for counsel to have

expertise in employment and criminal law. However, Hansen J disagreed with the Magistrate's

finding saying that experienced and competent junior counsel could have run the case even though a

conviction for OHP/L could have had “serious negative implications” and the possibility of a negative

impact on the sale of the business. In those circumstances, it was not open to the magistrate to

conclude that the test for allowing the fees to senior counsel was satisfied.

Re-opening the Prosecution case

In Burridge v Tonkin MC32/07, the question of re-opening the Prosecution case was raised. Williams

J held that a magistrate has a discretion in relation to an application to re-open the prosecution

case. However, the prosecution may call evidence at that stage only if the circumstances are very

special or exceptional and, generally speaking, not if the occasion for calling the further evidence

ought reasonably to have been foreseen.

R v Chin (1984-5) 157 CLR 671, applied.

In granting an application to re-open the prosecution case, factors which were relevant to the

magistrate's determination were the late service of the s58(2) notice and the fact that the operator

was absent from the court when the application for abridgment of time of service of the notice was

allowed. Also, it was relevant that the notice did not on its face draw the prosecutor's attention to the

challenge to the operator's authority and further that it was difficult to point to any resultant

unfairness to the defendant in granting the application.

Company's liability for regulatory offences

The Court of Appeal (Maxwell P, Chernov and Neave JJ A) recently had the occasion in ABC

Developmental Learning Centres Pty Ltd v Wallace MC33/07 to consider whether the company may

be liable for offences under the Children’s Services Act 1996 (‘Act’). In that case, a child aged nearly

three got out of the Learning Centre while the staff were not looking. Subsequently, charges were laid

against the company alleging that it failed to take reasonable precautions to protect the child from

hazards and failing to adequately supervise the child. The Court said that the duties imposed by

s27(1) of the Act on the proprietor and on a staff member are both directed at ensuring adequate

supervision, but their scope is different. The proprietor's duty is to ensure adequate supervision of all

children at all relevant times. The staff member's duty extends only to a child in the care of that staff

member. The duty under s27(1) of the Act has all the same characteristics as the duty under s21 of

the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 ('OHS Act'). A breach of s27 does not require proof of

mens rea. The offences are committed by the objective failure of the person to meet the specified

standard whether the failure was deliberate or inadvertent. Under s27(1), the proprietor has a duty

to ensure – that is, make certain – that a certain state of affairs exists viz adequate supervision of all

children. Like s21(1) of the OHS Act, s27(1) is framed to achieve a result. Unless there is adequate

supervision, the company is in breach. Liability under the section does not depend upon any failure

by the company itself, meaning by those persons who “embody the company”. If it is proved that

there was not adequate supervision, it is immaterial where in the organisation the failure occurred. It

will be a question of fact in each case whether there has been a failure to ensure adequate

supervision. In practice, the supervision of children at a children’s service will be wholly or very

largely the responsibility of the staff of the service, rather than of management. Whether a lapse in

supervision by a staff member will or will not constitute a failure by the proprietor to ensure

adequate supervision will depend on the court’s view of what the proprietor’s duty required in the

circumstances. No issue of that kind arose in the present case, since ABC conceded that there had

not been adequate supervision. Accordingly, it was open to the judge to conclude that the failure of

the staff members to ensure adequate supervision was attributable to ABC as proprietor.

"in connection with the driving of a motor vehicle"

A question that crops up occasionally is whether a person charged with an offence has committed it

in connection with the driving of a motor vehicle. In R v Novakovic MC34/07 the Court of Appeal

(Nettle, Ashley and Redlich JJ A) dealt with a defendant who was found guilty of offences which

included robbery of a motor vehicle and then driving it away. The Court held that despite the

potential breadth of the phrase "in connection with" in s28(1) of the Road Safety Act ('Act'), there

must be a substantial relation between the other offence and the driving of a motor vehicle in order

that the additional punishment of the driver licence cancellation may be imposed. In the present

case, the circumstances of taking the vehicle and driving it away unarguably met the substantial

connection test. Murdoch v Simmonds [1971] VR 887, followed; Rochow v Pupavac [1989] VR 73, not

followed. In determining the question of making an order disqualifying the defendant from obtaining

a driver licence, the Court said that a s28(1)(b) order has an intended punitive element and there

may be many cases where a period of disqualification would exceed the period of imprisonment. In

the present case, however, having regard to the defendant’s ability to rehabilitate, the relatively

35

37

37A

38

39

lengthy period of parole and his particular need for use of a vehicle in order to effectively resume

work after his release, a disqualification period of two years would aid his rehabilitation.

"On the cards" test – whether appropriate to apply

In DPP v Selway (Reasons for Ruling No 2) MC35/07, Cummins J took the opportunity to state that

the “on the cards” test is no longer appropriate. His Honour said frequently it has been said that the

test to be applied for the order of production or refusal of material in respect of which a claim of

public interest immunity is made is whether it is “on the cards” that the sought-for material would

materially assist the defence. Although that expression has judicial authority it is unhelpful and

should not be used. Metaphor illumines; it does not define. The test is whether it is reasonably

possible that the sought-for material would materially assist the defence. Legal definition should not

be measured by the company one keeps when fishing or playing cards. On the basis of the

authorities, the true test is whether there is a reasonable possibility that the sought-for information

would materially assist the defence. Probability is too high a standard. Mere possibility is too low.

The adverb “reasonably” gives proper scope to the judge to determine the issue responsibly and

objectively. Such a standard also is consonant with the principles of open justice. In ACC v Brereton

MC36/07 Smith J was considering an application to set aside a sub-poena which had been issued by

a person charged with a criminal offence. His Honour said that there is a number of cases in which

the test to be applied, including the often quoted so-called “on the cards” test, is considered. That

phrase and other phrases used by judges are attempts to state ways in which the ultimate question

might be approached in a particular case. The ultimate question, however, is whether there is a

legitimate forensic purpose which the subpoena will serve. It is necessary to consider, among other

things, the importance of the issue to which it is said the subpoena relates and the importance of the

document in question in the determination of that issue.

Bunning v Cross revisited

In DPP v Riley MC37/07, Hansen J discussed the well-known principles laid down in Bunning v

Cross and other cases. His Honour said that a magistrate has a discretion to exclude evidence on the

grounds of public policy. The discretion is enlivened only where the impugned conduct was the

means by which the evidence was obtained or where the obtaining of the evidence involved such

conduct. In Riley's case, the critical question was whether the evidence of the unlawful or improper

conduct of the police was the means by which the evidence was obtained or where the obtaining of

the evidence involved such conduct. The public policy discretion requires a balancing of competing

factors in the sense of examining the comparative seriousness of the offence charged and the

unlawful or improper conduct of the police. By failing to engage in such a balancing exercise, and

failing to exercise the discretion by reference to relevant criteria, the magistrate's discretion

miscarried. Bunning v Cross (1978) 141 CLR 54, and DPP v Moore (2004) 39 MVR 323; [2003] VSCA

90; MC20/03, applied.

Corporation in liquidation can make claim

In Bella Fresh Pty Ltd (in liq.) v Petrac and Anor MC37A/07, Robson J heard an appeal against a

magistrate’s finding that a company in liquidation could not make a claim to money without first

obtaining leave of the Court pursuant to s471B of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The claim

involved the sum of $25000 which was in the possession of a police officer. As the officer had formed

the view that the money was no longer entitled to remain in his possession, the officer made an

application pursuant to s125 of the Police Regulation Act 1958 to the Magistrates’ Court for an order

as to whom the money should be delivered. In granting the appeal and quashing the magistrate’s

decision, Robson J said that the company was not obliged to seek leave before making a claim to the

money. S471B did not apply to the police officer’s application and did not impede the action of the

liquidator in getting any assets of the company.

The self-represented litigant

In Tomasevic v Travaglini & Anor MC38/07, Bell J had some pertinent comments to make about the

self-represented litigant. His Honour stated that a judicial officer has a fundamental duty to ensure a

fair trial by giving due assistance to a self-represented litigant, whilst at the same time maintaining

the reality and appearance of judicial neutrality. The duty is inherent in the rule of law and the

judicial process. The human rights of equality before the law and access to justice specified in the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights are relevant to its proper performance. The

assistance to be given depends on the particular litigant and the nature of the case, but can include

information about the relevant legal and procedural issues. Fairness and balance are the

touchstones. Where a judicial officer conducted a short hearing in which the informant’s counsel was

called on to say very little, the judge did not explain to the self-represented applicant the procedures

that would be followed or the legal requirements that he had to satisfy, nor assist him to present his

case nor mention exceptional circumstances or prejudice to the informant’s case and the judicial

officer rejected the application on the basis that the delay had been too great, the judge failed to

properly perform his duty to ensure a fair hearing of the application and was in breach of the rules of

natural justice.

Forfeiture of bail orders

The Court of Appeal (Maxwell P, Vincent and Ashley JJ A) in Renate Mokbel v DPP (Vic and Cth)

MC39/07 rejected an appeal by Renate Mokbel against the forfeiture of bail order made by Gillard J.

40

41

42

The order was made due to the fact that Tony Mokbel failed to answer his bail on charges before the

Supreme Court. It was submitted that Gillard J should not have presided over the subsequent

application by Renate Mokbel for rescission of the forfeiture order. In rejecting the appeal, the Court

said that where a judge has made an order forfeiting bail pursuant to s6(1) of the Crown Proceedings

Act 1958, and an application for rescission or variation is later made, there is no reason in principle

why the same judge should withdraw from hearing the application. This practice has much to

commend it because the judge making the forfeiture order does so with knowledge of the background

of the trial and the circumstances of the non-attendance of the bailed person. Re Condon [1973] VR

427, followed. Further, Gillard J’s finding that Renate Mokbel was not a genuine surety in that she

had no entitlement to the property which was put up as security, was clearly open in the

circumstances and Gillard J was not in error in refusing the application to rescind the forfeiture

order.

Hire Purchase Agreement – goods repossessed – value of the goods

In Nathan v Esanda Finance Corp MC40/07, Harper J considered the question of the consequences

following the default by the hirer and the termination of the hire purchase agreement. His Honour

held:

1. Where pursuant to a hire purchase agreement a hirer was in default of instalments and a Notice of

Termination was served on the hirer, a formal assessment of the value of the goods should be made

and a determination made whether there was a contractual basis for making an allowance or

adjustment for their value in calculating the amount owing by the hirer.

2. Given that the person must take into account the value of goods repossessed or capable of being

repossessed, it is for that person to introduce evidence that prima facie establishes what the value is

if it appears that the goods are capable of repossession. If the goods are so capable, in those

circumstances it is incumbent upon that person to introduce evidence as to their value. Once that

evidence is introduced then, if the hirer seeks to contradict it, the hirer would have the evidentiary

burden of negating the prima facie position. The hirer could not simply sit back without any evidence

and impugn the value put forward by the person repossessing once that person gave evidence that

had the prima facie point.

Fair Trading aspects

In Euginia v Chong MC41/07, Bell J heard an appeal against a magistrate’s order dismissing a claim

based on misleading or deceptive representation and s10A of the Fair Trading Act 1985 (‘Act’). His

Honour stated that whether a representation is misleading or deceptive is a question of law that has

to be answered by reference to the words spoken in their individual context. It is common ground

that that question has to be considered from the point of view of the objective impact of the words, in

that context, on a reasonable person in the position of the parties. Accordingly, where a reasonable

person of business in the position of the parties would have understood a person's representation

that he would use his best endeavours to ensure that the tenant paid the rent on time, the

magistrate was not in error in deciding that the representation was not misleading or deceptive.

In relation to Section 10A(1) of the Act, His Honour said that it provides that a representation with

respect to a future matter (including the doing of an act) is taken to be misleading if the person does

not have reasonable grounds for making it. Under s10A(2), unless the person has adduced evidence

to the contrary, he or she will be deemed not to have had reasonable grounds for making the

representation. Accordingly, where a person represented he would use his best endeavours to

persuade and assist his brother to pay the rent on time, this was a representation to use those

endeavours in the future which was a representation as to that future matter. Therefore, the person

had to prove he had reasonable grounds for the representation made. In view of the fact that rent

had been paid for many years before the default and that the person making the representation was

in regular contact with the tenant and had considerable involvement in his financial affairs, it was

open to the magistrate to find that the person making the representation had satisfied the onus of

adducing evidence of reasonable grounds for making the representation.

Travel Agent and the law of contract

In Imaje v Taylor MC42/07, Bell J heard an appeal against a magistrate’s order dismissing a claim by

a travel agency for reimbursement for the provision of airline tickets to a traveller. When the traveller

requested the tickets, he paid for them by credit card. After the tickets were supplied but before the

date of travel, the airline (Ansett) collapsed financially. Whereupon the traveller requested the bank

to reverse the credit card transaction. Subsequently, the travel agent sued the traveller but was

unsuccessful before the magistrate. In allowing the appeal, Bell J stated that an agent (the travel

agent) is entitled to be indemnified by the principal (the traveller); however, the agent is not so

entitled (or to a handling charge) where the consideration flowing to the principal has totally failed.

As the travel agent was contracted by a traveller to obtain return airline tickets for specified travel

and it did exactly that, it represented full performance of the travel agent's contractual obligations.

Once the tickets were issued, the traveller was in a passenger-carrier relationship with the airline

operator. It did not destroy the consideration that had already passed from the travel agent to the

traveller under the agency contract. Accordingly, the magistrate was in error in dismissing the travel

agent's claim.

43

44

45

46

Drink/driving - Certificate signed by registered medical practitioner

In Stone v McIntyre MC43/07, Forrest J dealt with an appeal against a conviction of the defendant on

a drink/driving charge. As a result of the defendant being involved in a motor vehicle accident, she

was conveyed to a hospital where a blood sample was taken from her. At the subsequent hearing of

the charge, the certificate under s57(3) of the Road Safety Act 1986 (‘Act’) was admitted into

evidence. However, it disclosed that the person who signed the certificate was “A registered medical

practitioner or approved health professional”. Only a doctor can take a blood sample. It was

submitted that there was not sufficient evidence for the magistrate to find that a registered medical

practitioner took the sample of blood. In rejecting the appeal, Forrest J said that it is a necessary

part of the proofs for the prosecution of a charge under s49(1)(g) of the Act to establish that a doctor

has taken a sample of the driver's blood pursuant to s56 of the Act. In relation to the certificate, His

Honour said that where a driver involved in a motor vehicle accident had been conveyed to hospital

and had a sample of blood taken, it can be presumed that the person taking the sample was a doctor

who complied with all statutory requirements. Further, the letters 'MRCS' appearing in the certificate

after the printed word "qualifications" mean that a court can readily infer that the initials translate to

'Member of the Royal College of Surgeons' and accordingly, such a person was a registered medical

practitioner within the meaning of the Act. In those circumstances there was evidence upon which

the magistrate was entitled to conclude that a doctor had in fact taken the blood sample pursuant to

s56 and to find a charge under s49 of the Act proved.

Disposing of seized property

In Guss v Jacotine MC44/07, Hargrave J dealt with an appeal from a magistrate whereby the

defendants were found guilty of disposing of property which had been seized by the Sheriff under a

Warrant to Seize. As the size of the property was too large to be removed, the Sheriff left a notice to

the effect that the property had been seized. Some time after this, the defendants (Guss) sold their

interest in the property to another person. Hargrave J said that the scheme of sub-sections 111(7A)

and (7B) of the Magistrates’ Court Act 1989 (‘Act’) is to prevent any person, on notice of a seizure of

property, from dealing with the seized property without the consent of the sheriff or other person

executing the warrant. This prohibition serves to protect the interest of the judgment creditor in

having the judgment debt satisfied out of the proceeds of a sale of the seized property. The words

used in s111(7B) are unambiguous. The sub-section applies to: “A person who knows that the

property has been seized under a warrant to seize property ...”. These words focus upon the fact of

seizure under a warrant; not whether that seizure was valid or unimpeachable. Further, the

prohibition is not limited to the judgment debtor. It applies to any person who knows of the seizure.

S111(7B) of the Act should be construed to give effect to its underlying purpose or object. That

purpose is evident from the provisions of s111(7A) and s111(7B) when read together, the existence of

the interpleader procedure contained in r27.05 of the Magistrates’ Court Civil Procedure Rules 1999

and commonsense. Parliament has unambiguously prohibited all dispositions of seized goods

without the consent of the sheriff. The word "dispose" is of wide import and certainly includes a sale

or transfer of the legal title to seized property. By selling its legal interest in the property to the

purchaser, the defendants disposed of the property within the meaning of s111(7B) of the Act. There

is no dispute that each of the defendants aided, abetted, counselled or procured the disposition of

the property which was effected by the sale agreement. In those circumstances, the appellants were

rightly charged as principal offenders and convicted of a contravention of s111(7B) of the Act.

Terms of a contractual relationship

Moraghan & Anor v Cospak Pty Ltd MC45/07 was a case of determining the terms of a commercial

relationship between the parties. CP/L supplied wine bottles to M. a wine producer. However, the

bottles supplied were only suitable for sparkling wine not table wine. When the bottles were filled

with table wine, the corks did not provide an adequate seal. As a result, some of the wine was

spoiled. The parties met to discuss the problem but no firm agreement was obtained. Lasry J dealt

with an appeal from the magistrate’s decision finding on the claim by the supplier of the wine bottles.

Lasry J found that the evidence before the magistrate by objective standards of the subsequent

discussions did not indicate that the parties had reached an agreement which they intended to be

enforceable. Accordingly, it was open to the magistrate to conclude that whatever occurred in the

subsequent discussions, the parties did not make an agreement at that stage by which they all

accepted they were bound. In relation to the terms and conditions attached to the initial credit

application, the question was whether the bottles delivered were suitable for storage of table wine.

The evidence which was given before the magistrate demonstrated that there was an obligation on

CP/L to deliver table wine bottles and/or bottles fit for the purpose of storing table wine. In coming

to a different conclusion, the magistrate fell into error. In relation to the question of costs, where a

court is involved in determining the commercial relationship between parties and GST is part of that

commercial relationship, then GST should be included in the order. However, GST is not recoverable

where a claim is in the nature of damages rather than the supply of goods and services.

Security for costs - self-executing order

In Todarello Consolidated Investments Pty Ltd v Finch & Magistrates’ Court of Victoria MC46/07, Lasry

J dealt with an appeal from a magistrate’s order making a self-executing order on an application for

security for costs. When the respondent to the application failed to provide the security within the

time allowed, the self-executing order took effect thereby dismissing the respondent’s claim. Lasry J

stated that before the magistrate could make an order dismissing the action, he was obliged to

exercise the discretion required by Rule 31.04 of the Magistrates Court Civil Procedure Rules 1999.

This Rule provides that where a plaintiff fails to give the security required by an order, the Court may

dismiss the plaintiff's claim. The use of the word "may" in the Rule means that there is a discretion to

be exercised as to whether the action should be brought to an end by being dismissed. In the

circumstances, the magistrate exceeded his jurisdiction by making an order under Rule 31.04 at a

time when the conditions necessary to the exercise of his discretion had not yet been satisfied.

Further, although the magistrate gave no reasons, the reasons for making the order were obvious

from the surrounding circumstances.