Team Transformational Leadership, Trust, Satisfaction, And

advertisement

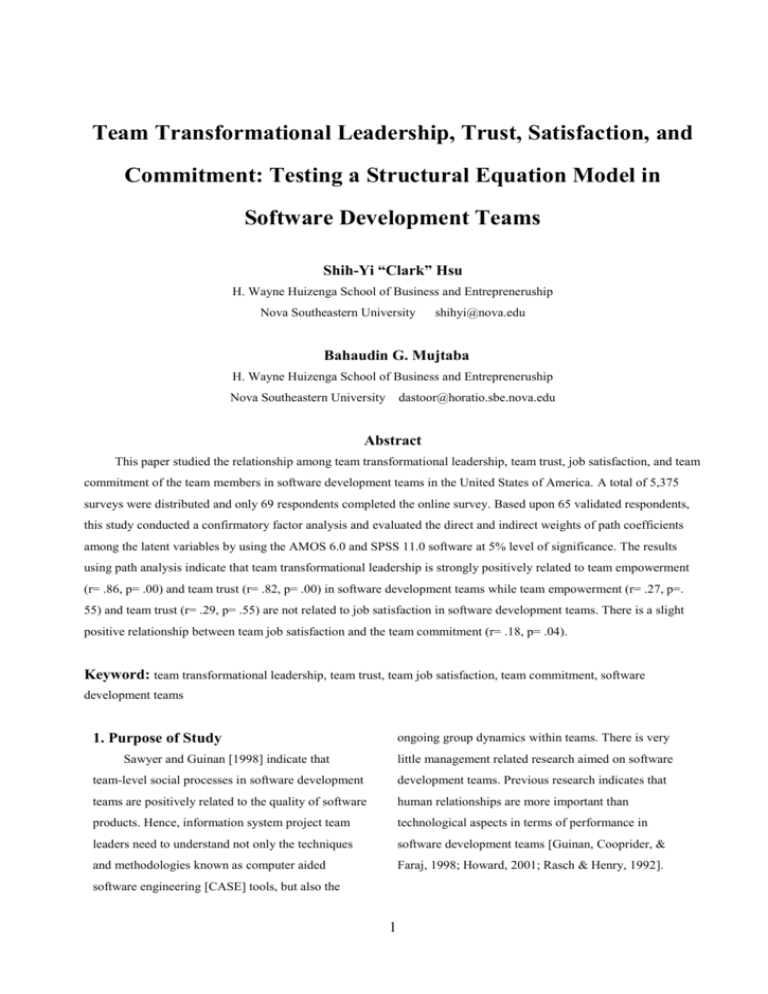

Team Transformational Leadership, Trust, Satisfaction, and Commitment: Testing a Structural Equation Model in Software Development Teams Shih-Yi “Clark” Hsu H. Wayne Huizenga School of Business and Entrepreneruship Nova Southeastern University shihyi@nova.edu Bahaudin G. Mujtaba H. Wayne Huizenga School of Business and Entrepreneruship Nova Southeastern University dastoor@horatio.sbe.nova.edu Abstract This paper studied the relationship among team transformational leadership, team trust, job satisfaction, and team commitment of the team members in software development teams in the United States of America. A total of 5,375 surveys were distributed and only 69 respondents completed the online survey. Based upon 65 validated respondents, this study conducted a confirmatory factor analysis and evaluated the direct and indirect weights of path coefficients among the latent variables by using the AMOS 6.0 and SPSS 11.0 software at 5% level of significance. The results using path analysis indicate that team transformational leadership is strongly positively related to team empowerment (r= .86, p= .00) and team trust (r= .82, p= .00) in software development teams while team empowerment (r= .27, p=. 55) and team trust (r= .29, p= .55) are not related to job satisfaction in software development teams. There is a slight positive relationship between team job satisfaction and the team commitment (r= .18, p= .04). Keyword: team transformational leadership, team trust, team job satisfaction, team commitment, software development teams 1. Purpose of Study ongoing group dynamics within teams. There is very Sawyer and Guinan [1998] indicate that little management related research aimed on software team-level social processes in software development development teams. Previous research indicates that teams are positively related to the quality of software human relationships are more important than products. Hence, information system project team technological aspects in terms of performance in leaders need to understand not only the techniques software development teams [Guinan, Cooprider, & and methodologies known as computer aided Faraj, 1998; Howard, 2001; Rasch & Henry, 1992]. software engineering [CASE] tools, but also the 1 The purpose of this paper studied the managers and workers, and internal and external relationship among team transformational leadership, circumstances [Sweeney & McFarlin]. team trust, job satisfaction, and team commitment of 2.1. The Group Dynamics The definition of the group dynamics is “the the team members in software development teams in the United States of America. social process by which people interact face-to-face 2. Theoretical Foundation in small groups” [Newstrom & Davis, 2002, p. 285]. In order to understand the role of teamwork in The founder of the group dynamics movement is the software development process, researchers have named Kurt Lewin in 1945 [Graham, 2002]. He adopted models from organizational behavior science, discovered that: such as leader-member exchange and group The group controlled through leadership dynamics. The model developed in this study depicts rather than force; ensured discipline through teamwork as relationships among team internal pressure; pooled thinking; respected transformational leadership, empowerment, trust, job the individual; and allowed all its members satisfaction, and commitment. to participate in deciding on things that There are three behavioral sciences: directly affected them in their work [p. psychology (the study of individual behavior), 2612]. 2.2. Teamwork sociology (the study of social behavior within societies, institutions, and group), and anthropology Walker Royce [1998, p. 43] indicated, (the study of origin, cultural development, and “Teamwork is much more important than the sum of behavior of person) [Robbins, 2003; Roth, 1993]. the individual” since a nominal engineering team can Organizational behavior is the core of the behavior succeed under a well-managed project. In addition, approach to management [DuBrin, 2002]. The early Leung Ho Tsoi [1999] concluded “The success of a scholars in the behavior school were Henry G. Gantt software project relies very much on a good and Hugo Munsterberg [George, 1972]. They management and control system which allows the believed the study of management should focus on development to satisfy the project objectives” [p. the center of human behavior and interpersonal 597]. Scott and Townsend [1994] reported that team relations [George]. process skills – (a) communication, (b) leadership, (c) There were three major key movements in goal setting, (d) cross training, (e) problem organizational behavior: the Hawthorne studies, the solving/decision making, (f) conflict resolution are human relation movement, and the contingency the essential elements for successful teamwork. approach to management and leadership [DuBrin, 2.3. Group 2002; Sweeney & McFarlin, 2002]. The study of Group has appeared in countless organizations, contingency approach “is derived from the four corporations, and human societies. A collection of studies of leadership styles” [DuBrin, p. 10]. This people in organization is called a group. However, approach argues that, “there is no single best way there are two types of group: formal and informal manage behavior” in order to effectively manage [Maurer, Shulman, Ruwe, & Becherer, 1995]. humans behavior [Sweeney & McFarlin, 2002, p. 6]. According to Maurer et al. [1995, p. 1411] “Formal It all depends on the interaction between various groups are those that give legitimacy by the 2 organization. Informal groups tend to more social in 2. Help the team move towards these goals. nature”. Bradford and Cohen [1998] pointed out that 3. Accomplish tasks given to them. “Group members represent the areas for which they 4. Meet deadlines. are held accountable. …The emphasis in groups is to 5. Attend team meetings. run efficient meetings with the aid of strong 6. Contribute to developing a productive leadership that focuses discussion.” [p. 129]. atmosphere within the team [p, 282]. “Group” is a general word in the research 2.7. Leadership Theory literature which includes all forms of teams and work Leadership in organization consisted of formal group [Guzzo & Dickson, 1996]. and informal leadership is defined as “the process of 2.4. Project teams guiding and directing the behavior of people in the In general, “project teams are time limited. work environment” [Nelson, 2000, p. 384]. The They produce one-time outputs, such as a new influence process of leadership in organization products or service to be marketed by the company, a involve a great deal of downward influence new information system, or a new plant” [Cohen & (top-down direction) between a leader and followers Bailey, 1997, p. 242]. (subordinates) [Pearce & Conger, 2003]. 2.5. Effectiveness of teams After reviewing 13 different perspectives of Cohen and Bailey [1997] classified leadership, Bass [1990] concluded that the roles of effectiveness of teams into three major facets from leadership is as “the focus of group processes, as a 54 journal articles between 1990 and 1996: quality of personality attribute, as the art of inducing products (performance), member attitudes (employee compliance, as an exercise of influence, as a satisfaction, commitment, and trust), and behavior particular kind of act, as a form of persuasion, as a outcomes (absenteeism, turnover, and safety). In power relation, as an instrument in the attainment of order to assist and guide management, this paper goals, as an effect of interaction, as a differentiated focuses on the individual or group levels of the role, and as the initiation of structure” [p. 20]. member attitudes in the real software industry. Leadership is a process of interacting between people (a leader and followers) and context, and 2.6. The role of team leader and members Brown and Dobbie [1999] described the roles producing outcomes (such as trust, customer of a team leader: satisfaction, high quality products) [Murphy, 1941]. 1. 2.8. Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Coordinate the activities of the team (tracking progress, scheduling work). During 1970s, LMX was revived and renamed 2. Motivate the team. (from VDL –Vertical Dyad Linkage Theory) by 3. Ensure the team communicates effectively. Dansereau, Graen, and Haga [1975], Graen and 4. Interface with supervisor; arrange meetings Cashman [1975], and Graen and Wakabayashi with client when necessary. [1994]. Leaders develop two different types of 5. exchange relationships with their followers over time: Set agendas for meetings [p. 282]. The roles of a team member include: in-group and out-group relationships. Unlike 1. traditional leadership model, leaders apply almost Help to set the team goals (project goals, task allocations). similar styles to all of the followers. The members 3 with in-group relationships are usually trusted and leadership focuses on distribution of individual to empowered by the leader. They “tend to land subordinates and top-to-down hierarchical influence desirable assignments, enjoy considerable autonomy, (one-way influence). However, Sivasubramaniam, et participate in decision making, and receive the lion’s al. [2002] indicated that “Team-level leadership is share of resource” [Sweeney & McFarlin, 2002, p. similar to individual-level leadership in that the 183]. There are three dimensions of relationships functional relationships hypothesized at the between leader and followers: fairness or individual level are expected to be ‘isomorphic’ with organizational justice [Scandura, 1999], trust [Dirks, the next level” (p. 68). In summary, leadership within 2000], and ethics [Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999]. a team presupposes that all team members are able to 2.9 Shared leadership contribute to each other in terms of leading. Shared leadership is different than traditional Team transformational leadership based on leadership. The definition of shared leadership is “a Bass’s [Bass & Avolio, 1995] model includes dynamic, interactive influence process among idealized influence (II), idealized behaviors (IB), individuals in groups for which the objective is to inspirational motivation (IM), intellectual stimulation lead one another to achievement of group or (IS), and individualized consideration (IC) [Avolio, organizational goals or both” [Pearce & Conger, et al., 2003]. 2003, p. 1]. 2.11. Team Empowerment 2.10. Team level Transformational Leadership Team empowerment has four dimensions: choice, meaningfulness, competence, and process Although there are various types and [Kirkman & Rosen, 1997]. Furthermore, Gorn and definitions of leadership, leadership typically is a Kanungo [1980] revealed that the more meaningful process of social influence for a particular purpose an employee's job was, the more satisfied the [Barge, 1996].Team transformational leadership is employee was with his or her job. Naturally, one type of team leadership [Avolio, Jung, Murry, employees will find more meaning in their jobs when Sivasubramaniam, & Garger, 2003]. They describe the scope of their activities is large [Griffin, 1991], team leadership can be described as occurring when which is often the case with empowered work teams “all members of the team collectively influence each [Wellins et al., 1991]. Thomas and Velthouse [1990] other toward accomplishing its goals” based upon defined psychological empowerment as intrinsic Team-member exchange (TMX) [Avolio, et al., 2003, motivation manifested in four cognitions reflecting p. 145; Sivasubramaniam, et al., 2002] but an individual's orientation to his or her work role: characterizing a team rather than a dyad . The term meaning, competence, self-determination, and “team leadership”, is also called “shared leadership, impact. peer leadership, or collective leadership” [Avolio, et 2.12. Team trust al., 2003; Sivasubramaniam, et al., 2002]. Team Team trust is a collective attribute which leadership is different from traditional leadership in involves multiple trustees within team members that leader behavior is shared by all members if the [Jarvenpaa, Knoll, & Leidner, 1998]. It is also called team inter-actively (two-way influence) and multiple collective trust. The definition of team trust is “the interacting [Pearce & Conger, 2003]. Traditional belief that an individual or group (a) makes 4 good-faith efforts to behave in accordance with any commitment to the team, workplace, division, and/or commitments both explicit and implicit, (b) is honest corporation” [Sano, 2002, p. 941]. The team in whatever negotiations preceded such commitment commitment has become one of important levels of and (c) does not take excessive advantage of another commitment. Team commitment is used “to describe even when the opportunity is available” [Cummings very different constructs, experiences, degrees of & Bromley, 1996, p. 303]. There are three stages of involvement and motivation” [Hopfl, 2001, p. 90]. trust building: deterrence-based trust, Moreover, based upon field study from 114 knowledge-based trust, and identification-based trust. technical people within a consulting firm conducted 2.13. Job Satisfaction by Vegt and his associates [2000], the cross-sectional Tymon and his associates [Thomas & Tymon, study found that both individual-level task 1994; Tymon, 1988] and Spreitzer and her colleagues interdependence and job complexity were positive [1997] discovered a link between empowerment and related to individual job satisfaction, team job satisfaction at the individual level of analysis. satisfaction, job commitment, and team commitment. Besides, people working in teams had higher levels Moreover, Scott, and Townsend [1994] found that of job satisfaction than workforce working in team commitment was correlated to team traditional settings within the same company performance. In addition, the aggressiveness toward [Cordery, Mueller, & Smith, 1991; Wall, Kemp, other people and the value employees place on Jackson, & Clegg, 1986]. Job satisfaction consists of autonomy were negatively correlated to team intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction [Weiss, England, commitment. & Lofquist, 1967]. The facets of challenge, 3.1.Hypotheses achievement, and ability utilization are part of the Figure 1 depicts the proposed relationships intrinsic satisfaction which concerns with direct job among team transformational leadership, team trust, experience. Additionally, extrinsic satisfaction is job satisfaction, and team commitment in comprised of supervision, company policies and development teams as an input-process-output (IPO) practices, and compensation which are related to model. It integrates into one research model team different people attitudes toward work environmental transformational leadership, empowerment, trust, job factors [Santana & Robey, 1994]. satisfaction, and commitment that were never 2.14. Team Commitment previously examined together in modeling the Business enterprisers are facing the interactions among team members as a whole. tremendous pressure of globalization and The hypotheses below articulate the expected competition, a more flexible and adaptive interrelationships among the variables, as illustrated organization has shifted to a team-based structure. in Figure 1: Recently, the research concentrates not only on Hypothesis H1a: Team transformational organizational level, but also commitment at the team. leadership is related to team empowerment in The definition of team commitment is “the relative software development teams. strength of an individual’s identification with, and Hypothesis H1b: Team transformational involvement in, a particular team” [Bishop & Scott, leadership is related to team trust in software 2000, p. 439]. “Effective teamwork is based on a development teams. 5 H1a Team Empowerment Team Job Satisfaction H2a Transformation Leadership H2b H1b H3 Team Commitment Team Trust Input Process Output Figure 1. Research model in software development team. Hypothesis H2a: Team empowerment is related Team transformational leadership (TTL) is to job satisfaction in software development teams. assessed with the Team Multifactor Leadership Hypothesis H2b: Team trust is related to job Questionnaire (TMLQ) [Sivasubramaniam, et al., satisfaction in software development teams. 2002]. 3.4.2. Team empowerment Hypothesis H3: The job satisfaction is related to team commitment in software development teams. This research measures team empowerment 3.2. Level of Analysis with two scales: an 8-item potency scale [Guzzo, The level of analysis is the individual level of Yost, Campbell, & Shea, 1993] and 18-item analysis. Characteristically, respondents can be empowerment inventory (EI) [Thomas & Tymon, arranged in hierarchical order. For example, the 1993, 1994]. Three of the four EI dimensions: organization, the group, and the individuals are meaningfulness, choice (autonomy), and progress moving from the macro level to the micro level. The (impact) [Guzzo, et al., 1993] are used. higher levels (such as the group level) incorporate of 3.4.3. Team trust lower levels, for example individual respondents Since "trust emerges in the team as members [Yammarino & Jung, 1998]. learn from their success and failures to rely on one 3.3 Scales and Measurement of Variables another"[Mayo, Meindl, & Paster, 2003, p. 211], team trust is defined as each team member’s For all scales a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 5 = "strongly agree", 3 = “moderately”, to 1 = perception of other members’ abilities, integrity, and "strongly disagree" provides the response format benevolence [Jarvenpaa, et al., 1998]. except the TMLQ with a 5-point Likert scale ranging 3.4.4. Job satisfaction from 5 = "frequently or always", 3 = “sometimes”, to Team level job satisfaction is measured with a 1 = "not at all". 4-item assessment developed by Thomas and Tymon 3.4 Measurement 3.4.1. Team transformational leadership [1994]. 3.4.5. Team commitment 6 for IB, α = .83 for IS, α = .82 for IM, and α = .84 for A variety of assessments of team-level team commitment exist in the previous literature, such as IC. Shapiro and Kirkman’s [1999] 3-item questionnaire, 4.2. Team empowerment Alutto and Hrebiniak’s [1975] 4-item questionnaire, Figure 3 presents the confirmatory factor March and Simon’s [1958] 5-item assessment, Rossy analysis results for team empowerment. The factor and Archibald [1992], and Bishop and Scott’s [2000] loadings for team empowerment were .55 for 8-item assessment. However, Bishop and Scott meaningfulness, .58 for potency, .81 for progress (as (2000) modified portions of the Organization impact), and .61 for choice (as autonomy), as Commitment Questionnaires (OCQ) short form depicted in Figure 3. Reliability estimates for the (Mowday, Steers, & Porter, 1979) to assess team facets of team empowerment (α) was .96 for level commitment. It is defined as “the relative meaningfulness, α = .92 for potency, α = .92 for strength of an individual’s identification with, and progress (as impact), and α = .87 for choice (as involvement in, a particular team” (Bishop & Scott, autonomy). 2000, p. 439). 4.3. Team trust 3.5. Criteria for acceptance / significance. The latent variable, team trust, used a 5-item The path analysis is used to test the scale. The levels of factor loadings for each item hypotheses because of its capability to evaluate appear in Figure 4. All items have factor loadings of causal relationships [Loehlin, 1987; Pedhazur, 1982]. .79 or greater. The Cronbach’s alpha of team trust The level of significance for testing the hypothesis is was .88. p = .05. If the null hypothesis (Ho) is not rejected, 4.4. Team job satisfaction this indicates that the hypothesis is accepted within Team job satisfaction was measured by using a 5% level of significance. Although there is 5% 4-item job satisfaction scale. The factor loadings are possibility that the null hypothesis is wrong, the all .91 or higher, as depicted in Figure 5. A reliability researcher has 95% of confidence that the null estimate for job satisfaction (α) was .94. hypothesis is accurate. 4.5. Team commitment 4. Statistic Tests This research measures team commitment with 4.1. Transformational leadership an 8-item team commitment scale. Figure 6 lists all Figure 2 presents the confirmatory factor factor loadings for the team commitment items, all analysis of team transformational leadership items. exceeding .70. The reliability analysis (α) of team Each of the five facets of team transformational commitment was .92. leadership exceeded the criterion of .5. The 5. Summary of Findings Cronbach’s alphas for the team transformational leadership dimensions all exceeded the conventional minimum requirement of .70, α = .85 for IA, α = .79 7 A Confirmatory Factory Analysis for Team Transformational Leadership Model 1 es2q21 .30 .02 S2Q21Option5 .89 S2Q16Option5 1.00 1 1 es2q16 .48 .70 1 es2q11 e1 Idealized Attributes S2Q11Option5 .37 1 es2q6 S2Q6Option5 .33 .86 1 es2q1 .83 S2Q1Option5 .62 S2Q22Option5 .54 1 es2q17 S2Q17Option5 1.30 1 S2Q12Option5 .36 e2 1.00 .89 .91 1 es2q12 .79 .03 1 es2q22 Idealized Behaviors .73 1 es2q7 S2Q7Option5 .35 es2q2 .20 1 es2q23 S2Q23Option5 .48 1 es2q18 S2Q18Option5 .39 1 .88 .71 Inspirational Motivation S2Q13Option5 .25 e3 1.00 .84 1 es2q13 .79 1 es2q8 S2Q8Option5 .50 1.00 .89 S2Q2Option5 .51 Transformational Leadership .71 1 .55 .81 .60 1 es2q3 .36 S3Q3Option5 1 es2q24 S2Q24Option5 .24 1 es2q19 S2Q19Option5 .45 .58 S2Q5Option5 1 1.00 1.00 Intellectual Stimulation e5 es2q15 .37 1 1 .29 .82 1 .54 es2q10 1 S2Q15Option5 Individualized Consideration .59 es2q4 S2Q10Option5 .46 S2Q14Option5 S2Q9Option5 .40 1 .84 1 es2q9 es2q5 .47 .72 e4 .77 1 es2q14 1 .10 .97 .63 S2Q20Option5 es2q20 .64 .75 1 S2Q25Option5 S2Q4Option5 es2q25 .50 Figure 2. The confirmatory factor analysis of team transformational leadership. Concerning the SEM analysis, AMOS 6.0 relationship between the job satisfaction and the job software was used to examine the research commitment (r= .18, p= .04). hypotheses and research model for fit in the sample 5.1. Conclusions data. The results (Figure 7) using path analysis The above summary demonstrates that the indicate that team transformational leadership is findings of this study contribute to the body of strongly positively related to team empowerment empirical literature regarding the individual attributes (r= .86, p= .00) and team trust (r= .82, p= .00) in of, and attitudes leadership and team qualities in software development teams. In addition, team software development teams in the United States. empowerment (r= .27, p=. 55) and team trust (r= .29, The results in figure 7 indicate that team p= .55) are not related to job satisfaction in software transformational leadership is strongly, positively development teams. There is a slight positive related to team empowerment and team trust in the software development teams. Both job satisfaction 8 and the team commitment also have a positive direct relationship. These finding have a great deal of applicability in the workplace. 5.2. Recommendations 1. This study could be applied to other fields such as software project managers, hardware or software 9 A Confirmatory Factory Analysis for Team Empowerment Model 1 es3q6 S3Q6Option5 .32 es3q5 es3q4 1 1 S3Q2Option5 .88 1 1 1.00 S3Q12Option5 .34 1 e2 .86 1 es3q9 .58 .82 S3Q8Option5 .16 1.00 1 es3q7 .92 S3Q7Option5 .17 1 es3q20 S3Q17Option5 .10 .90 1 es3q16 Progress (Impact) 1.00 1 es3q17 .83 S3Q18Option5 .11 .65 S3Q16Option5 .09 .78 1 es3q15 S3Q15Option5 .12 1 es3q26 .68 S3Q23Option5 .27 .95 S3Q22Option5 .39 1 es3q21 Choice (Autonomy) 1.00 1 es3q22 1 S3Q24Option5 .50 1 es3q23 .39 e4 .53 S3Q25Option5 .69 1 es3q24 .69 S3Q26Option5 .59 1 es3q25 .81 1 1 es3q18 .12 e3 .60 S3Q19Option5 .68 Empowerment .66 S3Q20Option5 .54 1 es3q19 Potency S3Q9Option5 .33 1 es3q8 1 .87 S3Q10Option5 .34 .55 .16 .81 S3Q11Option5 .20 1 es3q10 .91 S3Q1Option5 .02 es3q11 Meaningfulness S3Q3Option5 .06 es3q12 1 1.00 1 .05 es3q2 e1 .88 S3Q4Option5 .15 es3q3 es3q1 S3Q5Option5 .22 .26 .89 .80 1 S3Q21Option5 .15 1.08 Figure 3. A confirmatory factory analysis for team empowerment. A Confirmatory Factory Analysis for Team Trust Model es4q1 1 S4Q1Option5 .29 es4q2 1 .95 S4Q2Option5 .18 .92 .45 es4q3 1 S4Q3Option5 .79 Team Trust .35 .83 es4q4 es4q5 1 .23 1 S4Q4Option5 1.00 S4Q5Option5 .25 Figure 4. A confirmatory factory analysis for team trust. 10 A Confirmatory Factory Analysis for Job Satisfaction Model es4q6 1 S4Q6Option5 .59 .91 es4q7 1 S4Q7Option5 .22 .95 1.77 Job Satisfaction .94 es4q8 1 S4Q8Option5 .33 1.00 es4q9 1 S4Q9Option5 .18 Figure 5. A confirmatory factory analysis for team job satisfaction. A Confirmatory Factory Analysis for Team Commitment Model 1 es4q10 .89 es4q11 .97 1 S4Q10Option5 S4Q11Option5 .71 es4q12 1 .27 1.00 S4Q12Option5 .75 es4q13 es4q14 1 .47 1 .21 .79 S4Q13Option5 Team Commitment .89 .83 S4Q14Option5 .87 es4q15 1 .21 S4Q15Option5 .70 .98 1 es4q16 .46 es4q17 .21 1 S4Q16Option5 S4Q17Option5 Figure 6. A confirmatory factory analysis for team commitment. system administration, or IT departments. conduct other survey media for enlarging and 2. encouraging the size of respondents. The sample size is too small to represent the software publishing industry. A larger sample size is Potential respondents could be concern the required for SEM technique to calculate the proposed internet security threat or against company policy in relationships [Kline, 1998]. The suggestion is to answering the online survey. Using traditional self-administered questionnaires with return address 11 A path diagram of Research Model es3q24 es3q23 .23 1 es3q22 .14 1 Potency Meaningfulness .18 1 Choice (Autonomy) Progress (Impact) .76 .72 es3q21 .06 1 1.00 .96 Empowerment S4Q10Option5 .90 1 es4q10 .98 1 1 S4Q11Option5 D2 .09 es2q5 Idealized Attributes D5 D4 1 1 .91 1 es2q10 .75 1.63 .27 1.00 .16 .80 1 es2q15 .13 .18 .48 Transformational Leadership .89 Intellectual Stimulation 1.00 .71 .96 es4q13 .22 1 es4q14 .20 1 S4Q15Option5 es4q15 .46 1 .96 1 1 S4Q13Option5 S4Q14Option5 Inspirational Motivation .24 es4q12 .47 .76 .90 TeamCommitment Job Satisfaction 1 es2q20 es2q25 1 S4Q12Option5 1.01 .80 Idealized Behaviors .17 es4q11 .28 .71 .14 .86 1 .29 .82 Individualized Consideration .91 .95 S4Q16Option5 1.00 .95 es4q16 .20 S4Q17Option5 1 .12 es4q17 D3 S4Q6Option5 1 Chi-square = 684.365 (df = 294) p = .000 GFI = .621, AGFI = .548 CFI = .763, RMSEA = .144 Team Trust .59 .99 S4Q1Option5 es4q1 es4q7 .23 1 1 es4q9 es4q8 .32 .18 1 es4q4 es4q3 .34 1 es4q6 S4Q9Option5 S4Q5Option5 1 1 es4q2 .19 S4Q4Option5 S4Q3Option5 1 1 S4Q8Option5 1.00 .81 .82 S4Q2Option5 1 .26 .93 S4Q7Option5 es4q5 .26 .25 Figure 7. The path diagram results for research model. appears outside when folding properly instead of Leadership. (pp. 143-172). Thousand Oaks, on-line survey could be better than the online survey. CA: Sage Publications. 2. 5.3. Further Study 1. This study could be conducted in a single large Barge, J. K. (1996). Leaderships Skills and the Dialectice of Leadership in Group Decision software publisher with documents on the history of Making. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole. the company for case study. (Eds.), Communication and group decision 2. making (pp. 55-80). (2nd ed.).Thousand Oaks, This study could be deployed in other countries or regions for comparing and contrasting. 3. CA: SAGE Publications. The population could sample the university 3. Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, students majoring in computer science, information Character, and Authentic Transactional system, or other related. Leadership Behavior. Leadership Quarterly, 4. 10(2), 181-217. This study could examine mediator variables such as team empowerment, team trust, and job 4. Bishop, J. W., & Scott, K. D. (2000). An satisfaction. Examination of Organizational and Team References Commitment in a Self-Directed Team 1. Avolio, B. J., Jung, D. I., Murry, W., Environment. Journal of Applied Psychology, Sivasubramaniam, N., & Garger, J. (2003). 85(3), 439-450. Assessing Shared Leadership: Development of 5. Bradford, D. L., & Cohen, A. R. (1998). Power a Team Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. up: transforming organizations through shared In C.L. Pearce & Jay A. Conger (Eds.), Shared leadership. New York: John Wiley. Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of 6. Brown, J., & Dobbie, G. (1999). Supporting and Evaluating Team Dynamics in Group 12 Projects. The Proceedings of the Thirtieth Business and Management (pp. 2610-2616). Sigcse Technical Symposium on Computer (2nd ed.). (Vols. 1-8). London: Thomson Science Education March 24 - 28, New Learning. Orleans, LA, 281-285 7. 8. 9. 15. Cohen, S. G., & Bailey, D. E. (1997). What Redesign on Employee Perceptions, Attitudes, Makes Teams Work: Group Effectiveness and Behaviors: a Long-Term Investigation. Research from the Shop Floor to the Executive Academy of Management Journal, 34, Suite. Journal of Management, 23(3), 239-290. 425-435. Cordery, J. L., Mueller, W. S., & Smith, L. M. 16. (1998). Enabling Software Development Team Autonomous Group Working: a Longitudinal Performance During Requirements. Definition: Field Study. Academy of Management Journal, a Behavioral versus Technical Approach. 34, 464-476. Information System Research 9(2), 101–125. Cummings, L. L., & Bromiley, P. (1996). The 17. 12. Teams in Organizations: Recent Research on and Validation. In Kramer, R. M., & Tyler, T. Performance and Effectiveness. Annual R. (Eds.), (1996). Trust in Organizations: Review of Psychology, 47, 307-338. 18. (Ed.), (2001). Organizational Behavior Publications. Reassessed (pp. 86-103). London: Sage Dirks, K. T. (2000). Trust in Leadership and Publishtions. 19. Howard, A. (2001). Software Engineering Basketball. Journal of Applied Psychology, Project Management. Communication of 85(6), 1004-1012. ACM, 44(5), 23–24. DuBrin, A. (2002). Fundamentals of 20. Jarvenpaa, S. L., Knoll, K., & Leidner, D. E. Organizational Behavior. (2nd ed.). Australia (1998). Is Anybody Out There? Antecedents of Cincinnati, OH: South-Western Thomson Trust in Global Virtual Team. Journal of Learning. Management Information Systems, 14(4), George, C. S. (1972). The History of 29-64. 21. Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and Practice of Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Structural Equation Modeling. New York: The Gorn, G. J., & Kanungo, R. N. (1980). Job Guilford Press. Involvement and Motivation: Are Intrinsically 14. Hopfl, H. (2001). Motivation. In E. Wilson. 302-330). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Management Thought (2nd ed.). Englewood 13. Guzzo, R. A., & Dickson, M. W. (1996). Organizational Trust inventory: Development Team Performance: Evidence from NCAA 11. Guinan, P. J., Cooprider, J.G., & Faraj, S. (1991). Attitudinal and Behavioral Effects of Frontiers of Theory and Research (pp. 10. Griffin, R. W. (1991). Effects of Work 22. Kirkman, B. L., & Rosen, B. (1997). A Model Motivated Managers More Job Involved? of Work Team Empowerment. In R. W. Organizational Behavior and Human Woodman, & W. A. Pasmore. (Eds.), Research Performance, 26, 265-277. in Organizational Change and Development Graham, P. (2002). Human Relations. In M. (pp. 131-167). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Warner. (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of 13 23. 24. Loehlin, J. C. (1987). Latent Variable Models. 33. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Management: A Unified Framework. Reading, Maurer, G. J., Shulman, M. J., Ruwe. L. M., & MA: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Becherer, C. R. (1995). Encyclopedia of 25. 34. 27. (Eds.), (2002). International Encyclopedia of Mayo, M., Meindl, J. R., & Paster, J. C. Business and Management. (2nd ed.). (Vols. (2003). Shared Leadership in Work Teams: a 1-8). London: Thomson Learning. 35. Systems Development Effects on Job Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership Satisfaction of Systems Professionals. (pp. 193-214). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Proceedings of the 1994 Computer Personnel Publications. Research Conference on Reinventing Is: Nelson, D. L. (2000). Organizational Behavior: Managing Information Technology in Foundations, Realities, and Challenges. (3rd Changing Organizations: Managing ed.). Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College Information Technology in Changing Publisher. Organizations, 184-191. Newstrom, J. W., & Davis, K. (2002). 36. development: Processes and performance. IBM Work. (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Systems Journal, 37, 4, 552-568. 37. 31. Why Some Succeed and Others Fail. Those Years Ago. In C. L. Pearce & J. A. HRMagazine, 39(8), 62-68. 38. Sivasubramaniam, N., Murry, W. D., Avolio, the Hows and Whys of Leadership. (pp. 1-18). B. J., & Jung, D. I. (2002). A Longitudinal Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Model of the Effects of Team Leadership and Pedhazur, E. J. (1982). Multiple Regression in Group Potency on Group Performance. Group Behavior Research. (2nd ed.). New York: & Organization Management, 27(1), 66-96. 39. Spreitzer, G. M., Kizilos, M. A., & Nason, S. Rasch, R.H., & Henry L. Tosi. (1992). Factors W. (1997). A Dimensional Analysis of the Affecting Software Developers' Performance: Relationship Between Psychological An Integrated Approach. MIS Quarterly, 16(3), Empowerment and Effectiveness, Satisfaction, 395–413. and Strain. Journal of Management, 23, Robbins, S. P. (2003). Organizational 679-704. Behavior. (10th ed.). NJ: Upper Saddle River. 32. Scott, K. D., & Townsend, A. (1994). Teams: Pearce, C. L., & Conger, J. A. (2003). All Holtz, Rinehart, & Winston. 30. Sawyer, S., & Guinan, P. J. (1998). Software Organizational Behavior Human Behavior at Conger (Eds.), Shared Leadership: Reframing 29. Santana, M., & Robey, D. (1994). Controlling J. A. Conger (Eds.), Shared Leadership: Higher Education. 28. Sano, Y. (2002). Commitment. In M. Warner. Business. Detroit, MI: Gale Research. Social Network Approach. In C. L. Pearce, & 26. Royce, W. (1998). Software Project 40. Sweeney, P. D., & McFarlin, D. B. (2002). Roth, W. F. (1993). The Evolution of Organizational Behavior: Solutions for Management Theory: Past, Present, Future. Management. Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin. Orefield, PA: Roth & Associates. 41. Thomas, K. W., & Tymon, W. G. Jr. (1993). Empowerment Inventory. NY: XICOM. 14 A Confirmatory Factory Analysis for Team Trust Model 1 es4q1 S4Q1Option5 .29 42. 1 es4q2 .18 Thomas, K. W., & Tymon, W. G. Jr. (1994). Quality, Productivity, and Participation. San Does Empowerment Always.95 Work: Francisco: Jossey-Bass. S4Q2Option5 Understanding the Role of Intrinsic Motivation 50. and Personal Interpretation. .92 Journal of Management Systems, 6, 1-13. Yammarino, F. J., & Jung, D. I. (1998). Asian Americans and leadership: A Levels of Analysis Perspective. The Journal of Applied .45 .79 Velthouse, 43. 1 Thomas, K. W., & B. A. (1990). Team Trust es4q3 S4Q3Option5 .35 Cognitive Elements of Empowerment: An Behavioral Science, 34(1), 47-68. "Interpretive" Model of .83 Intrinsic Task es4q4 1 .23 44. Motivation. Academy of Management Review, 1.00 15,S4Q4Option5 666-681. Tsoi, L. H. (1999). A Framework for Management Software Project Development. 1 es4q5 .25 Proceedings of the 1999 ACM Symposium on S4Q5Option5 Applied Computing, San Antonio, TX USA, February 28 - March 2, 1999, analysis 593-597. for team trust. Figure 4. A confirmatory factory 45. Tymon, W. G. Jr. (1988). An empirical investigation of a cognitive model of empowerment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Temple University, Philadelphia. 46. Vegt, G., Emans, B., & Vliert, E. (2000). Team Members' Affective Responses to Patterns of Intragroup Interdependence and Job Complexity. Journal of Management, 26(4), 633-655. 47. Wall, T. D., Kemp, N. J., Jackson, P. R., & Clegg, C. W. (1986). Outcomes of Autonomous Workgroups: A Long Term Field Experiment. Academy of Management Journal, 29, 280-304. 48. Weiss, D. J., England, G. W., & Lofquist, L. H. (1967). Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation, No. 22). MS: University of Minnesota Press. 49. Wellins, R. S., Byham, W., & Wilson, J. (1991). Empowered Teams: Creating Self-Directed Work Groups that Improve 15