Memories3 - honeycombe family history archive

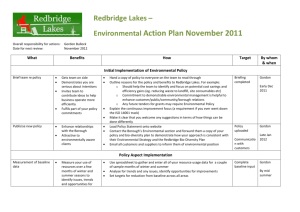

advertisement