closing greeting (3:15)

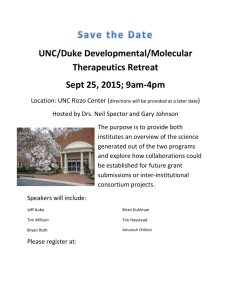

advertisement