Zahn2011 - University of Edinburgh

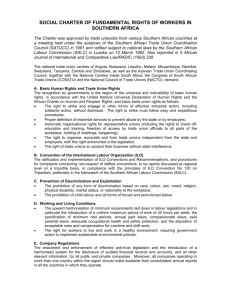

advertisement