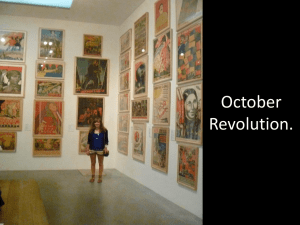

I. Mintz: October Days 1917

advertisement