Chapter 2 - Huntingdon College

advertisement

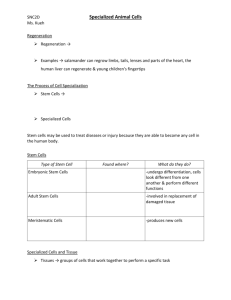

Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines and Arguments utlining is one of the most useful critical thinking skills you can learn, one that will benefit you in your writing endeavors far beyond this public speaking module. An outline helps you lay out your ideas by structuring them in a coherent and logical order. Additionally, an outline helps you spot “holes” in your writing and flaws in the arguments you construct. The purpose of this chapter is to provide you with practical advice to develop more coherent and stronger speeches. Speaking days are busy days. Depending on your instructor, you might have multiple assignments to submit on these days. At a minimum, you will be asked to submit a formal full content/full sentence outline on the day you are scheduled to speak. In this chapter you will find additional guidance on what your instructor might expect in terms of an outline, standard outlining conventions, tips, and strategies for preparing speaking notes on index cards. Following the guidelines and advice in the chapter can be a key to constructing an original and successful speech. A sample formal sentence outline of a persuasive speech is also included. Although this chapter is intended to offer guidelines and advice on how to prepare your speech, your instructor might have individual preferences for how your outlines and note cards are to be prepared. Therefore, we have indicated some of the areas where we believe instructors might differ in their approach and emphasis. O Argument Construction Behind your outline and note cards lies the central message or argument that you want to relay to your audience. To a large extent, your ability to construct a solid argument will determine the effectiveness of your speech at persuading your listeners. When you properly construct an argument, you are providing reasons for the claims advanced in your message (Lucas, 2007). The claims that you advance are conclusions, requiring proof or evidence that you want your listeners to believe or do (Lucas, 2007). Thus, the evidence you use in your speech and the claims that you make work together to create your argument. Your ability to carefully construct an effective argument can either demonstrate your critical thinking skills or potentially expose the logical fallacies in your argument. Critical thinking refers to your ability to demonstrate focused and organized thought about the logical relationships among ideas, the differences between opinion and fact, and the credibility of evidence (Lucas, 2007). A fallacy, on the other hand, can weaken your argument by using erroneous reasoning (Lucas, 2007). Thus, constructing an organized speech is one aspect of critical thinking. It is entirely possible, though, to present an organized speech that does not demonstrate other aspects of critical thinking, or that even commits fallacies in reasoning. Your task is to carefully construct your speech in such a way that it presents a logically organized argument that uses sound reasoning and credible evidence. Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments Once you have discussed your speech topic with your instructor and researched the materials for your speech, your next task is to think critically about the argument that you want to make in your speech. You will want to carefully evaluate the evidence you have gathered on your topic and decide how to arrange these materials in your speech. Therefore, it is helpful to know how arguments can be structured effectively. Toulmin Model of Argumentation Stephen Toulmin (1958) developed a model for structuring arguments that is generally well respected. The Toulmin Model of Argument emphasizes six elements that function as a general framework for argument construction and analysis (Toulmin, 2003). According to Toulmin the six elements of a well-structured argument are: 1. Claim: the fact, value, or policy statement that you offer for the audience’s consideration. 2. Data: the evidence or proof that you provide to support the claim. Data can come in many forms, including expert testimony, numbers and statistics, research surveys, examples, and analogies. 3. Warrant: the link between the data and your claim. In a logic class the instructor might refer to the warrant as “reasoning.” Two basic types of warrants are inductive and deductive. Inductive is where you reason from specific data to a general conclusion and deductive is where you reason from a general agreed upon premise (serving as data) to a specific conclusion. 4. Backing: additional data that is used to support the warrant. For example, if the audience is unlikely to believe the link between the data and the claim, additional backing should be provided. 5. Reservations: arguments that could be made counter to your position. Your position can be strengthened substantially if you anticipate reservations, or counterarguments, that might be made against your position and answer them. 6. Qualifiers: language that reflects the certainty or strength of your claim. For example, you should use words like “probably,” “likely,” “generally,” and “might” to indicate the strength of your claim. When constructing your formal sentence outline, keep these six elements of Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation in mind. Typically, if you have researched your topic well, you will be able to find plenty of data to support the claims that you want to make in your speech. Be careful, though, to state your claims and warrants clearly rather than relying on your data to make these statements for you. One mistake that some speakers commit is to expect their data to do all the talking for them. The data should serve to support the claim you are making, but cannot be a substitute for the claim itself. In addition, once you have presented a piece of data, be sure to explain the warrant. In other words, explain how the data that you just presented ties back into the claim that you began with. Some beginning speakers might find the idea of presenting reservations to be confusing. For instance, a speaker might think that by presenting reservations that a person with an opposing point of view might advance, that the speech is weakened. However, the audience is more likely to perceive the speaker as credible if she or he admits that reservations exist. Moreover, when the speaker presents answers to these reservations, the audience gets a better sense of the speaker’s entire position. So, although it may seem counterintuitive to do so, 12 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments presenting reservations serves to enhance your argument rather than weaken it. In communication we also refer to the reservation as presenting a two-sided argument. Ethicality of your Messages In constructing your argument, you have an obligation to construct ethically responsibility messages that present your point-of-view for the situation you are speaking in. Not all situations allow or call for certain topic discussions. Your classroom, as a positive learning environment, is one such situation. To test the ethicality of any message you construct, apply these ten questions from Gaut and Perrigo (1998, p. 294): 1. In determining your position regarding a topic, have you adequately examined all related facts, weighted them accordingly, and separated facts from present loyalties? 2. Have you carefully looked at the issues and facts to determine how an “opponent” might view them? Have you taken your “opponent’s” point of view into account as you have constructed your message? 3. Have you closely examined the history and context of all facts to ensure that none have been taken out of context? 4. To whom do you give your loyalties (i.e.: self, family, race, gender, boss, company, society, religion)? Have these loyalties impacted your message in any way? If yes, how? 5. What is your intention in presenting the message? What are the probable consequences of making this presentation? Could limitations of knowledge on your part lead to harm rather than good? 6. Whom could your message injure or adversely affect? Could you conduct a discussion with the potentially affected parties prior to the presentation? 7. Are you sure your position will be valid in the long term as well as the short term? 8. Could you present this message to your boss, spouse, children, society, or creator without any qualms? 9. What is the potential of your message if it is understood? What if it is misunderstood? 10. Under what conditions would you allow exceptions to your point of view? Formal Sentence Outline The development of your argument is given logical form and order through the construction of your outline. A formal, full sentence outline is similar to a script of a play. All the ideas in your speech should appear in your formal sentence outline. In that sense, the term “outline” is misleading since it is not just an outline, but also the entire content of your speech. The formal, full sentence outline is a tool to help you develop a stronger, better, and more 13 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments structured speech. Instructors of speech emphasize formal, full sentence outlines because those outlines ensure that your central idea and main points are focused, in a logical order, and are backed with adequate support or evidence. Additionally, a formal sentence outline is a way to make sure you have all the required parts of a speech, such as transition statements or an adequate conclusion. While reviewing your formal sentence outline you can detect flaws in your speech; for example, you might see that your support material is not appropriate for the claim you are making, or you might see that your introduction is two pages long while your conclusion is only four sentences in length. Thus, the outline helps you fix these flaws and develop a better-structured speech. When constructing your formal sentence outline, be sure to: 1. Use a consistent numbering and symbol scheme. The body of your speech will typically develop 2 or 3 main points or claims. Main points are the key ideas of your speech. Designate these main points with Roman numerals (I, II, and III). Develop each main point with at least 2 subpoints that provide the reasons for the main point or claim you are making. Designate the subpoints with capital letters (A, B, and C). The principle of division states that if a point is divided, it must result in at least two parts (Lucas, 2007). So, each subpoint that is divided will have at least 2 sub-subpoints, which provide support, examples, or explanation for the subpoint. Designate the sub-subpoints with Arabic numerals (1, 2, and 3). 2. Use proper indentation and margins to indicate subordination of ideas. The main point, its subpoints, and sub-subpoints work together as a unit. Always state your main points first and then reinforce them by providing subpoints and sub-subpoints. The subpoints and sub-subpoints develop and strengthen the main point. In your outline, subpoints are subordinated to the main idea or claim, and the sub-subpoints are subordinated to the subpoints. The indentation of certain items on the outline illustrates the principle of subordination, which holds that the less important the information, the greater the number of indentions from the left-hand margin (Lucas, 2007). Do not indent the main points (I, II, III). But, do indent the subpoints (A, B, C) under each main point, and also indent sub-subpoints (1, 2, 3) under each subpoint. It is best if you input the outline structure yourself rather than allowing your word processing software to automatically outline for you. Properly indented, the body of your speech will look like this: I. Main point A. Subpoint 1. Sub-subpoint 2. Sub-subpoint B. Subpoint 1. Sub-subpoint 2. Sub-subpoint II. Main point A. Subpoint 1. Sub-subpoint 2. Sub-subpoint B. Subpoint 14 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments 1. Sub-subpoint 2. Sub-subpoint 3. Use only one idea in each point of your outline. Each item (main point, subpoint, or sub-subpoint) should convey only a single thought or idea. Clarity is a vital component of effective speaking, so restrict yourself to one idea per item. Overloading too many ideas into a single line of outline structure can be confusing. Remember, unlike a reader, an audience member cannot go back to what you said if they did not understand the first time around. Your instructor will likely say that you need to subdivide your ideas more thoroughly if he or she sees several sentences or a long paragraph next to an item. 4. Fulfill other requirements. You will submit a formal sentence outline when you speak. This outline should be written using full sentences - not single words, phrases or sentence fragments. Remember that full sentences end with a period, question mark, or exclamation point. The four parts of your introduction and the four parts of your conclusion should be clearly labeled, as indicated on the example outline shown later in this chapter. We suggest that you write out your formal sentence outline as you would deliver it on the day you present. It is also helpful if you use brackets or parentheses to indicate things you will do while speaking; for example, gestures you want to use, times you want to move a few steps to help the audience visualize your outline, times to change your visual aid(s), or dramatic pauses for effect. You should also check to see if your instructor has other specific requirements, since she or he will be the one grading your outline. 15 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments Sample Formal Sentence Outline Student Name Oral Presentation Assignment FYEx 103 Title of Speech: Supporting Stem Cell Research Specific Purpose: To persuade my audience to support stem cell research. Thesis Statement: Stem cell research should be increased by increasing government funding and relaxing existing restrictions enacted by the Bush administration. INTRODUCTION I. Opening that gains the audience’s attention: In the summer of 1996, Muhammad Ali, arguably the greatest boxer to enter the ring, stood with trembling hands as he lit the torch signaling the beginning of the summer Olympic Games in Atlanta. Ali’s hands shook not because of the emotion of the moment, but because of Parkinson’s disease. Only one year before, in Culpepper, Virginia, Christopher Reeve, who is best known for his lead role in Superman, was flung from his horse and suffered a broken spine near his C1 and C2 vertebrate. At the time of his death on October 11, 2004, Reeve had not achieved his dream of walking again. Seven years before Ali’s appearance at the Olympic Games, Ronald Reagan, the 40th president of the United States, left office and all but removed himself from public life due to the progressively debilitating effects of Alzheimer's. Although each of these men retains a unique identity, each also holds something in common: Their ailments are potentially curable through research on stem cells. II. Link that relates the topic to the audience: For many of us, reflecting on our own family history reveals cases of cancer, Lou Gehrig’s disease, diabetes, paralysis, or other debilitating, chronic, and life threatening illnesses. To help improve the lives of our loved ones, and even potentially ourselves, Huntingdon College students should be concerned about advancements in stem cell research. III. Credibility statement that relates the speaker to the topic: Although I am not a research scientist or an expert on medical ethics, I have followed this controversy for several years and engaged in intensive research about the stem cell debate. IV. Statement of the central idea and preview of the organization of the speech: Federal funding for stem cell research should be increased and unnecessary restrictions on such research should be lifted. After first, discussing what stem cell research is and why it is so controversial, I will next discuss the problems with current policies on stem cell research, and finally cover why I think this research should be expanded. 16 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments Transition statement: First, stem cell research is one of the most important areas of scientific exploration because of its potential for medical advancement. At the same time, stem cell research is highly controversial. BODY I. The science and controversy surrounding stem cell research remain part of an ongoing public debate. A. Stem cell research is an outgrowth of the human genome project. Once scientists discovered the basic genetic makeup of human beings, they were able to begin deciphering the programming of certain cells in the human body. 1. Gretchen Vogel, writing in a 1999 issue of Science, explained that after studying human cells, scientists discovered that some cells, called stem cells, are generic cells that can be quickly programmed to serve a variety of functions in the body (Vogel, 1999). 2. Since discovering stem cells, scientists have identified and explored two types. a. The first form, embryonic stem cells, come from human embryos and can literally be programmed into any type of human tissue (Vogel, 1999). b. A second type of stem cells, called partly differentiated stem cells, are harvested from adults (Vogel, 1999). c. Both embryonic stem cells and partly differentiated stem cells are used but the latter are more limited in their potential programming. For instance, they might only be able to produce various blood, muscle, or nerve cells. 3. The importance of stem cells lies in their adaptability (Vogel, 1999). a. Stem cells are comparable to utility players in baseball, or what a football coach might call an “athlete.” Just as utility players or athletes can be used to fix holes in a team, stem cells can be used to fix problems in a person’s body, regardless of whether it is a muscle problem, a nerve problem, or even an organ failure. b. Many diseases are caused by a loss of certain cell types. According to Soren Holm, of the Institute of Medicine, Law and Bioethics at the University of New Hampshire, diseases like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer's, and ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease all result from damaged cells in the central nervous system. In theory, Stem cells could be programmed to replace cells damaged by these diseases (Holm, 2002). c. Another illustration of stem cell therapy is using stem cells to create new heart muscles after a person suffers a massive heart attack. Similar procedures could be used to replace other organs like the pancreas for those who have pancreatic cancer (Holm, 2002). B. With the promise of curing such significant diseases, it may be surprising that everyone does not support stem cell research. In fact, this type of research remains controversial, and much of this controversy results from the way that stem cells are collected. 1. Laurent Belsie, writing in a March 2001 issue of the Christian Science Monitor, points out that the harvesting of embryonic stem cells requires the destruction of a human embryo (Belsie, 2001b). This loss of potential human life causes many 17 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments conservative and religious groups to oppose stem cell research. Mainly, this argument assumes that our society will begin to de-value life when embryos are viewed as disposable. 2. Other moral arguments against stem cell research revolve around what Dr. Patrick Guinan, a medical ethicist at the University of Chicago, calls the Frankenstein myth (Guinan, 2002). a. According to Guinan (2002), the Frankenstein myth is a recent creation of a “theme recurrent from the beginning of literature…the pursuit of unrestrained or forbidden knowledge” (p. 306). b. In short, Guinan (2002) and others worry that our desire to cure all disease using any available means could permanently alter and corrupt the human gene pool—causing even more devastating outcomes than the diseases these therapies are intended to cure. Transition statement: These moral issues have not gone unheard. Next, I will describe current restrictions on stem cell research as well as the problems with those restrictions. II. The issues with current government policies on stem cell research are far reaching. A. According to an August, 2004 story on CNN, President Bush shaped current government policy on stem cell research in a 2001 executive order attempting to strike a middle ground in the stem cell debate (First lady defends Bush on stem cell research, 2004). 1. Bush’s policy provided $25 million dollars in federal funding for stem cell research. 2. Federal funding was only made available for research on currently harvested stem cell lines. 3. Through this order, the President was able to advance stem cell research but was also able to quell religious opposition since no new embryos could be destroyed for government-funded research (First lady defends Bush on stem cell research, 2004). B. Although Bush’s policy might initially seem reasonable, this policy could be harmful in the long run. 1. First, the Bush policy does not prohibit private sector research on stem cells. a. According to a story on CNN’s website, private companies can do anything from cloning to wholesale destruction of hundreds of embryos to conduct research (Kahn, 2001). b. Because private companies are able to avoid the ethical requirements placed on government-funded research, widespread abuse could occur. c. At the very least, scientists worry that private companies, driven by profit, will limit the distribution of scientific findings or even access to stem cell lines by other researchers (Kahn, 2001). 2. Second, limiting government research to the current 60 lines of stem cells is detrimental to the overall research effort. a. Dr. Jeffrey Kahn, of the center of Bioethics at the University of Minnesota, points out that “60 stem cell lines won’t be enough to satisfy all the research needs as we move forward in this area” (2001, n.p.). b. Why is 60 not enough? 18 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments Transition statement: Because the potential benefits of stem cell research outweigh the potential costs, the government should increase funding and gradually lift the restrictions on the number of federally funded stem cell lines. III. Stem cell research should be expanded. A. First, increased funding would speed therapeutic applications of stem cell research. 1. Although the $25 million allotted by the Bush administration was a step in the right direction, Kahn (2001) points out that the speed with which research can be conducted, verified, and moved into clinical situations is directly related to the amount of funding provided. 2. Therefore, increased funding can assist in speeding up research. B. Second, expanding the number of stem cell lines would be beneficial and morally justified. 1. By having more than 60 lines available, scientists would have better opportunities to verify findings and create usable clinical treatments. 2. Even more important, additional lines would safeguard against deterioration of the current lines. C. The most important reason for the federal government to increase its support of stem cell research is to maintain control over stem cell research. 1. Federal funding allows the government to set ethical guidelines for how embryos are used. For instance, the government could limit the use of embryos to those not used by couples who undergo fertility treatment. 2. Second, Holm (2002) points out that a lack of federal funding will shift both scientific expertise and gains to other countries or the private sector. In short, the intellectual and economic capital associated with stem cell research could shift to other countries. 3. Increased federal funding could prevent this devastating outcome. Transition statement: Although there does not appear to be a miracle solution to the issue of stem cell research, what is clear is a need for the federal government to reexamine its current policy stance. CONCLUSION I. Forewarn audience that the speech is ending: Keeping this information in mind, I would like to conclude with several key thoughts. II. Remind audience of main points: I first discussed what stem cell research is, from both scientific and moral vantage points. Second, I explained some of the problems associated with the current federal policies on stem cell research. And, third, I justified why the federal government should increase its support for such research. 19 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments III. Specify what the audience should do as a result of the speech: Although the issue of stem cell research continues to be a topic of debate and discussion, it is imperative that Huntingdon College students, as voting-age citizens, recognize the potential consequences of this technology. In particular, we must recognize the tremendous benefits to be gained from revised federal mandates. IV. Close with impact: Ronald Reagan and Christopher Reeve have already passed on and it is uncertain as to whether or not Muhammad Ali will be able to benefit from stem cell therapy. However, the potential for substantial advances in medical knowledge and practice lies within us all in the form of stem cells. Allowing science to unlock these super cells is unquestionably a moral imperative. Please support increased funding for stem cell research from the federal government. 20 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments References Belsie, L. (2001a, August 16). Bush stem-cell decision may be first of many. Christian Science Monitor, p. 2. Belsie, L. (2001b, March 13). Should US fund embryonic-cell research? Christian Science Monitor, p. 2. First Lady defends Bush on stem cell research (2004). Retrieved August 12, 2004 from www.cnn.com. Guinan, P. (2002). Bioterriorism, embryonic stem cells, and Frankenstien. Journal of Religion & Health, 41, 305-310. Holm, S. (2002). Going to the roots of stem cell controversy. Bioethics, 16, 493-507. Kahn, J. (2001, August 10). Jeff Kahn: Debate over ethics of stem cell research. Retrieved August 12, 2004, from http://arachieves.cnn.com/2001/COMMUNITY/08/10/kahn.cnna/. Scherer, R. (2004). States race to lead stem-cell research. Christian Science Monitor, 96, 1. Vogel, G. (1999). Harnessing the power of stem cells. Science, 283, 1432-1435. Note that the references in this example are written in APA style, and attached to the outline on a separate page. Contact your instructor to determine how he or she wants you to construct your reference list or bibliography. Information on APA, MLA and other citation styles can be found on-line as well as in Houghton Memorial Library. 21 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments Applying the Toulmin Model to the Stem Cell Speech Earlier in this chapter, we said that you should keep Toulmin’s Model of Argument in mind as you construct your formal sentence outline. One of the best ways to learn to do this is to examine a sample speech using Toulmin’s model. Consider, for instance, the sample speech on stem cell research that was just presented. Can you spot the six elements of Toulmin’s model in the stem cell outline? Remember, the six elements are: claim, data, warrant, backing, reservations, and qualifiers. First of all, what is the claim that is made in the stem cell outline? Begin with the central claim of the speech. The central claim can be found in the thesis statement. Is it a fact, value, or policy statement? We would have to conclude that the central claim is persuasive since the speaker advocates increased government funding and relaxed restrictions, which require policymaking. Next, what is the data that is used in the stem cell outline? Recall that the speaker used a range of data, including expert testimony, statistics, and examples. Often, speakers will employ many types of data in their speech. Now, what warrants are offered in the stem cell outline? These should appear in several different places in the outline, right? For each piece of data that the speaker provides, there should be a warrant that links the data back to the speaker’s claim. Notice that throughout the body of the outline, the speaker will narrate between various pieces of data. For instance, consider the transition statement just prior to the third main point in the body of the speech. This transition statement serves to summarize the data that was presented in the second main point and ties the data back into the thesis statement. An important point to learn here is that well crafted speeches will have multiple warrants supporting the same overall claim. Can you find a place in the stem cell outline where backing is used? Remember that backing refers to additional data that is used to support a warrant. Are there places where the speaker has reinforced a warrant in order to further convince the audience of a point that might otherwise be dismissed? Consider subpoint C of the third main point in the body of the outline; here, the speaker provides additional support or backing for increasing federal funding. Specifically, the speaker argues that federal funding is one mechanism for the government to maintain control over stem cell research. Are there reservations mentioned in the stem cell outline? Remember that reservations are counterarguments that someone who would take a position opposite that of the speaker might say. So, does the speaker seem to anticipate what an opponent might say in some places? Take a look at subpoint B of the second main point in the body of the outline. Here, the speaker says “although Bush’s policy might initially seem reasonable…” (this is what an opponent might be thinking) “…this policy could be harmful in the long run” (this is the speaker’s answer to what the opponent could be thinking). So, by presenting reservations and answering those reservations, the speaker is actually able to refute arguments that an opponent might present. In the end, this strategy can help the speaker to be more persuasive since it may address what the audience is thinking as they are listening to the speech. Moreover, the audience may consider the speaker to be even more credible since the speaker did partially present the other side of the issue. Finally, what qualifiers are used in the stem cell outline? Is there language that qualifies the strength or certainty of the claims that the speaker makes? You can probably spot several word choices that are examples of qualifiers. For instance, take another look at the third subsubpoint under the C subpoint of the third main point in the body of the outline. Here, the 22 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments speaker writes “increased federal funding could prevent this devastating outcome.” Is there a qualifier in this sentence? The word “could” is certainly not as strong as the word “will.” What if the speaker had used “will” instead of “could” in this statement? Then, the speaker would have possibly been overstating the conclusions. In sum, we can analyze the strength of a speaker’s argument by looking for the six elements of Toulmin’s model in the speech. If elements are missing when they should be present, that could be a sign that the speaker needs to reconsider how the argument is being constructed. So, after you have written a rough draft of your outline, look for these six elements. Is one missing? Do you make warrants when you need to? Are there reservations that ought to be mentioned? You can use Toulmin’s model to double-check you outline before you turn it into your instructor. Speaking Note cards Although you will turn your formal sentence outline in to your instructor prior to your speech, you will not actually speak from this outline. Instead, you will condense your outline into speaking note cards that you will be able to refer to during your speech. It is helpful to keep in mind a couple of tips when you write your speaking note cards. First, remember that the objective of extemporaneous speaking is a “conversational” style of delivery (Lucas, 2007). Accordingly, the note cards you use to speak from should not be a “script” or duplication of your formal sentence outline. You should not read your speech like a manuscript. Second, you should rehearse your speech before your class presentation. This does not mean that you memorize your speech, but you should practice until you can easily recall the main points you want to deliver. Speaking note cards should not be used as a “crutch,” but are there to help you should you forget the point that comes next, as well as to help you with the information you want to quote and cite correctly. Use speaking note cards as a reminder of your key points. Include phrases, important words, quotations, statistics, and references that are essential to your speech. You will find it helpful to list, in order, the main points and subpoints of your speech in shorthand, so you can follow the planned structure and not “skip” important points. Think of your note cards as the “speaking outline” (for an example see Lucas, 2007, p. 263). You might also like to include notes or reminders to yourself such as when to pause, or to speak more slowly, or to avoid fillers such as “ums” and “ahs.” If there is a difficult word or a foreign term that you may stumble while pronouncing, you could spell out the word phonetically to avoid mispronouncing the term. Use only one side of the card for notes, and number the cards to avoid confusion. Be sure not to write too small on your note cards, or you may have difficulty spotting the information during your speech. For the speeches you will be delivering in your first year experience class, we believe you should be able to prepare adequate speaking notes using only four or five 3 x 5-inch index cards. Too many cards give space for too much text, thus tempting you to read too much from them. The order of the cards could also become mixed up and you could find yourself in a panic to find the right card. Brevity and ordering are critical for speaking note cards. 23 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments The order and content of your note cards should be as follows (be sure to check with your instructor for additional recommendations or specific guidelines): Note card 1 is for your introduction. The notes on this card can be fairly detailed, and contain key words and cues for the four steps of your introduction. You might want to include your attention-getter or any quotations verbatim - the way you want to speak them. This card should also contain sufficient notes to help you remember your transition into the body of your speech. Note cards 2, 3, and 4 are for the body of your speech. Allot one card per main point. On each card, use keywords to outline a main point, its subpoints and sub-subpoints. If you are using quotations or statistics, include these in your notes, as well. Include oral source citations, and instructions about visual aids where needed. Again, remember to include notes for your transition statement. Note card 5 is for your conclusion. Again, the notes can be fairly detailed to help you recall the four steps of your closing, and you might want to include your final closing statement verbatim. Again, your instructor might also have his or her own preferences about how you prepare your speaking note cards. Remember these are guidelines; the note cards are a tool to help you during your speech. So develop them according to your specific needs, while using these pointers as a guide. The key is to avoid having too many note cards with too much writing. 24 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments Chapter References Gaut, D. R., & Perrigo, E. M. (1998). Business and professional communication for the 21st century. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Lucas, S. E. (2007). The art of public speaking (9th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. Toulmin, S. E. (1958). The uses of argument. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Toulmin, S. E. (2003). The uses of argument (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 25 Chapter 2 ● Constructing Outlines & Arguments 26