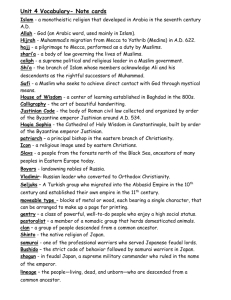

Chapter Fourteen - AP World History

advertisement

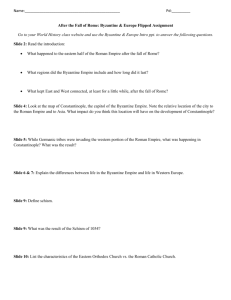

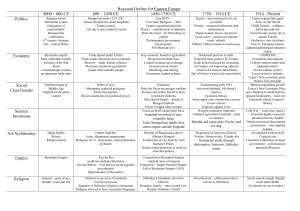

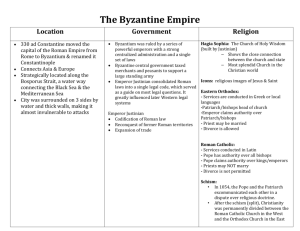

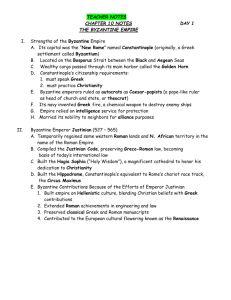

CHAPTER 9 Civilization in Eastern Europe: Byzantium and Orthodox Europe Chapter Outline Summary I. The Byzantine Empire A. Emperor Constantine 4th century C.E., Constantinople Empire divided capitals at Rome and Constantinople Greek language official language from 6th century B. Justinian’s Achievements Justinian attempted reconquest of Italy Slavs, Persians attack from east building projects Hagia Sophia legal codification C. Arab Pressure and the Empire’s Defenses Center of empire shifted to east Constant external threatened Arab Muslims Bulgars defeated by Basil II, 11th century D. Byzantine Society and Politics Emperors resembled Chinese rulers court ritual head of church and state Sophisticated bureaucracy opened to all classes Provincial governors Economic control regulation of food prices, trade silk production Trade network Asia, Russia, Scandinavia, Europe, Africa Arts creativity in architecture II. The Split Between Eastern and Western Christianity A. The Schism Separate paths Patriarch Michael 1054, attacks Catholic practice mutual excommunication, pope and patriarch B. The Empire’s Decline Period of decline from 11th century Seljuk Turks took most of Asian provinces 255 1071, Manzikert Byzantine defeat Slavic states emerged Appeal to west brought crusaders 1204, Venetian crusaders sacked Constantinople 1453, Constantinople taken by Ottoman Turks 1461, empire gone III. The Spread of Civilization in Eastern Europe Influence through conquest, conversion, trade Cyril, Methodius, to Slavs Cyrillic script A. The East Central Borderlands Competition from Catholics and Orthodox Greeks Catholics Czechs, Hungary, Poland regional monarchies prevailed Jews from Western Europe IV. The Emergence of Kievan Rus’ A. New Patterns of Trade Slavs from Asia iron working, extended agriculture mixed with earlier populations family tribes, villages kingdoms animistic 6th, 7th centuries Scandinavian merchants trade between Byzantines and the north c. 855, monarchy under Rurik center at Kiev Vladimir I (980-1015) converts to Orthodoxy controlled church B. Institutions and Culture in Kievan Rus’ Influenced by Byzantine patterns Orthodox influence ornate churches icons monasticism Art, literature dominated by religion, royalty Free farmers predominant Boyars, landlords less powerful than in the West C. Kievan Decline Decline from 12th century rival governments succession struggled Asian conquerors Mongols (Tartars) 13th century, took territory Traditional culture survived 256 D. The End of an Era in Eastern Europe Mongol invasions usher in new period East and West further separated Chapter Summary Chapter Summary. In addition to the great civilizations of Asia and Africa forming during the postclassical period, two related, major civilizations formed in Europe. The Byzantine Empire, with its capital in the great city of Constantinople, was based in western Asia and southeastern Europe, and expanded into eastern Europe. The other was defined by the influence of Catholicism in western and central Europe. The Byzantine Empire, with territory in the Balkans, the Middle East, and the eastern Mediterranean, maintained very high levels of political, economic, and cultural life between 500 and 1450 C.E. The empire continued many Roman patterns and spread its Orthodox Christian civilization through most of eastern Europe, Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia. Catholic Christianity, without an imperial center, spread in western Europe. Two separate civilizations emerged from the differing Christian influences. Vladimir and Russian Orthodoxy. A choice confronted the Russian king Vladimir in the late 10th century: to maintain the traditional religion, or adopt either Catholicism or Byzantine Orthodoxy. His decision to adopt the religion of the Byzantine Empire was probably easy, attaching the early Russian kingdom to the sphere of the successful Greek empire. Much more than religion was involved. Alliance with Constantinople meant being part of a larger commercial world, a gateway to international trade, and an influx of cultural influences. It also solidified the division between Greek, Orthodox Byzantium, and Latin, Catholic Western Europe. The Byzantine Empire retained more continuity with the Roman Empire than did Europe, and a higher level of urban civilization in the postclassical period. Constantinople far outstripped any European city in this period in size and sophistication. Byzantine influence stretched to the Balkans, and north into Russia. Significant commonalities existed in the two halves of the former Roman Empire: spread of Christianity, northern regions coming belatedly into contact with international trade, and both looking back to a common Roman past. However, the two spheres also remained separate, developing distinctively, with surprisingly little contact. The Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire, once part of the greater Roman empire, continued to flourish in the eastern Mediterranean base after Roman decline. Although it inherited and continued some of Rome’s heritage, the Byzantine state developed its own form of civilization. The Origins of the Empire. In the 4th century C.E., the Emperor Constantine established a capital at Constantinople. Rule of the vast empire was split between two emperors, one ruling from Rome, one from Constantinople. Although Latin served for a time as the court language, from the 6th century Greek became the official tongue. The empire benefited from the high level of civilization in the former Hellenistic world and from the region’s prosperous commerce. It held off barbarian invaders and developed a trained civilian bureaucracy. Justinian’s Achievements. In the 6th century Justinian, with a secure base in the east, attempted to reconquer western territory, without lasting success. These campaigns weakened the empire as Slavs and Persians attacked the frontiers, and also created serious financial pressures. Justinian rebuilt Constantinople in classical style; among the architectural achievements was the huge church of Hagia Sophia. His codification of Roman law reduced legal confusion in the empire. The code later spread Roman legal concepts throughout Europe. Arab Pressure and the Empire’s Defenses. Justinian’s successors concentrated upon the defense of their eastern territories. The empire henceforth centered in the Balkans, and western and central Turkey, a location blending a rich Hellenistic culture with Christianity. The revived empire withstood the 7thcentury advance of Arab Muslims, although important regions were lost along the eastern Mediterranean and the northern Middle Eastern heartland. The wars and the permanent Muslim threat had significant cultural and commercial influences. The free rural population, the provider of military recruits and taxes, 257 was weakened. Aristocratic estates grew larger, and aristocratic generals became stronger. The empire’s fortunes fluctuated as it resisted pressures from the Arabs and Slavic kingdoms. Bulgaria was a strong rival, but Basil II defeated and conquered it in the 11th century. At the close of the 10th century, the Byzantine emperor was probably the strongest ruler of the time. Byzantine Society and Politics. Byzantine political patterns resembled the earlier Chinese system. An emperor, ordained by god and surrounded by elaborate court ritual, headed both church and state. Women occasionally held the throne. An elaborate bureaucracy supported the imperial authority. The officials, trained in Hellenistic knowledge in a secular school system, could be recruited from all social classes, although, as in China, aristocrats predominated. Provincial governors were appointed from the center, and a spy system helped to preserve loyalty. A careful military organization defended the empire. Troops were recruited locally and given land in return for service. Outsiders, especially Slavs and Armenians, accepted similar terms. Over time, hereditary military leaders developed regional power and displaced better-educated aristocrats. Socially and economically, the empire depended upon Constantinople’s control of the countryside. The bureaucracy regulated trade and food prices. Peasants supplied the food and provided most tax revenues. The large urban population was kept satisfied by low food prices. A widespread commercial network extended into Asia, Russia, Scandinavia, western Europe, and Africa. Silk production techniques brought from China added a valuable product to the luxury items exported. Despite the busy trade, the large merchant class never developed political power. Cultural life centered upon Hellenistic secular traditions and Orthodox Christianity. Little artistic creativity resulted, except in art and architecture. Domed buildings, colored mosaics, and painted icons revealed strong links to religion. The Split Between Eastern and Western Christianity. Byzantine culture, political organization, and economic orientation help to explain the rift between the eastern and western versions of Christianity. Different rituals grew from Greek and Latin versions of the Bible. Emperors resisted papal attempts to interfere in religious issues. In 1054, the Patriarch Michael attacked Catholic practices more strenuously, raising contentious issues that separated the churches. The conflict resulted in mutual excommunication by the Patriarch and the Roman pope. Even though the two churches remained separate, they continued to share a common classical heritage, and informal contact persisted. The Empire’s Decline. A long period of decline began in the 11th century. Muslim Turkish invaders, the Seljuks, seized almost all of the empire’s Asian provinces, removing the most important sources of taxes and food. The empire never recovered from the loss of its army at Manzikert in 1071. Independent Slavic states appeared in the Balkans. An appeal for western European assistance did not help the Byzantines, and indeed, crusaders led by Venetian merchants sacked Constantinople in 1204. Italian cities, secured special trading privileges. The greatly reduced empire struggled to survive for another two centuries against western Europeans, Muslims, and Slavic kingdoms. In 1453, the Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople and by 1461 the empire had disappeared. The Spread of Civilization in Eastern Europe. The Byzantine Empire’s influence spread among the people of the Balkans and southern Russia through conquest, commerce, and Christianity. In the 9th century, the missionaries Cyril and Methodius devised the Cyrillic script for the Slavic language, providing a base for literacy in eastern Europe. Unlike western Christians, the Byzantines allowed the use of local languages in church services. The East Central Borderlands. Both eastern and western Christian missionaries competed in eastern Europe. Roman Catholics, and their Latin alphabet, prevailed in the Czech region, Hungary, and Poland. Competition in this area between western and eastern influences was long-standing. A series of regional monarchies with powerful, landowning aristocracies developed in Poland, Bohemia, and Lithuania. Eastern Europe also received an influx of Jews from the Middle East and western Europe. They were often barred from agriculture, but participated in local commerce. They maintained their own traditions, and emphasized education for males. The Emergence of Kievan Rus’. Slavic peoples from Asia migrated into Russia and eastern Europe during the period of the Roman Empire. They mixed with and incorporated earlier populations and later invaders. The Slavs worked iron and extended the amount of land under cultivation in Ukraine and 258 western Russia. Political organization centered in family tribes and villages, organized ultimately into regional kingdoms. The Slavs followed an animist religion, and had rich traditions of music and oral literature. Scandinavian traders during the 6th and 7th centuries moved into the region along its great rivers and established a rich trade between their homeland and Constantinople. Some won political control. A monarchy emerged at Kiev around 855 under the legendary Danish merchant, Rurik. The loosely organized state flourished until the 12th century. Kiev became a prosperous commercial center. Contacts with the Byzantines resulted in the conversion of Vladimir I (980–1015) to Orthodox Christianity. The ruler, on the Byzantine pattern, controlled church appointments. Kiev’s rulers issued a formal law code. They ruled the largest single European state. Institutions and Culture in Kievan Rus’. Cultural, social, and economic patterns developed differently from the western European experience. Kiev borrowed much from Byzantium, but it was unable to duplicate its bureaucracy or education system. Rulers favored Byzantine ceremonials and the concept of a strong central ruler. Orthodox Christian practices entered Russian culture: devotion to divine power and to saints, ornate churches, icons, and monasticism. Polygamy yielded to Christian monogamy. Almsgiving emphasized the obligation of the wealthy toward the poor. Literature, using the Cyrillic alphabet, focused on religious and royal events, while art was dominated by icon painting and illuminated religious manuscripts. Church architecture adapted Byzantine themes to local conditions. Peasants were free farmers, and aristocratic landlords (boyars) had less political power than similar westerners. Kievan Decline. Kievan decline began in the 12th century. Rival princes established competing governments while the royal family quarreled over the succession. Asian invaders seized territory as trade diminished due to Byzantine decay. The Mongol invasions of the 13th century incorporated Russian lands into their territories. Mongol (Tartar) dominance further separated Russia from western European developments. Commercial contacts lapsed. Russian Orthodoxy survived because the tolerant Mongols did not interfere with Russian religious beliefs or daily life as long as tribute was paid. Thus when Mongol control ended in the 15th century, a Russian cultural and political tradition incorporating the Byzantine inheritance reemerged. The Russians claimed to be the successors to the Roman and Byzantine states, the “third, new Rome.” Thinking Historically: Eastern and Western Europe: The Problem of Boundaries. Determining where individual civilizations begin and end is a difficult exercise. The presence of many rival units and internal cultural differences complicates the question. If mainstream culture is used for definition, the Orthodox and Roman Catholic religions, each with its own alphabet, can be used to distinguish East from West. Political organization is harder to use because of the presence of loosely organized regional kingdoms. Commercial patterns and Mongol and Russian expansion also influenced cultural identities. The End of an Era in Eastern Europe. With the Mongol invasions, the decline of Russia, and the collapse of Byzantium, eastern European civilization entered into a difficult period. Much of Kievan social structure disappeared, but Christianity and other socio-political and artistic patterns survived. Western and Eastern Europe evolved separately, with the former pushing ahead in power and crosscultural sophistication. GLOBAL CONNECTIONS: Eastern Europe and the World. During the postclassical era, the Byzantine Empire was an active link between the Mediterranean and northern Europe. Russia’s location opened it to influences from both western Asia and Europe. Because Russia’s main contact with the wider world was through Byzantium, that empire’s decline, and the Mongol conquest, brought isolation. KEY TERMS Justinian: 6th-century Byzantine emperor; failed to reconquer the western portions of the empire; rebuilt Constantinople; codified Roman law. Hagia Sophia: great domed church constructed during reign of Justinian. 259 Body of Civil Law: Justinian’s codification of Roman law; reconciled Roman edicts and decisions; made Roman law coherent basis for political and economic life. Belisarius: (c.505–565); one of Justinian’s most important military commanders during the attempted reconquest of western Europe. Greek Fire: Byzantine weapon consisting of mixture of chemicals that ignited when exposed to water; used to drive back the Arab fleets attacking Constantinople. Bulgaria: Slavic kingdom in Balkans; constant pressure on Byzantine Empire; defeated by Basil II in 1014. Icons: images of religious figures venerated by Byzantine Christians. Iconoclasm: the breaking of images; religious controversy of the 8th century; Byzantine emperor attempted, but failed, to suppress icon veneration. Manzikert: Seljuk Turk victory in 1071 over Byzantium; resulted in loss of the empire’s rich Anatolian territory. Cyril and Methodius: Byzantine missionaries sent to convert eastern Europe and Balkans; responsible for creation of Slavic written script called Cyrillic. Kiev: commercial city in Ukraine established by Scandinavians in 9th century; became the center for a kingdom that flourished until the 12th century. Rurik: legendary Scandinavian, regarded as founder of Kievan Rus’ in 855. Vladimir I: ruler of Kiev (980–1015); converted kingdom to Orthodox Christianity. Russian Orthodoxy: Russian form of Christianity brought from Byzantine Empire. Yaroslav: (975–1054); Last great Kievan monarch; responsible for codification of laws, based on Byzantine codes. Boyars: Russian land-holding aristocrats; possessed less political power than their western European counterparts. Tatars: Mongols who conquered Russian cities during the 13th century; left Russian church and aristocracy intact. LESSON SUGGESTIONS Leader Analysis Peoples Analysis Conflict Analysis Change Analysis Societal Comparison Document Analysis Dialectical Journal Justinian, Theodora Byzantines, early Russians Arab incursions, Catholicism and Orthodoxy Byzantine Empire: 565-1200 Byzantine Empire and early Russia Russia Turns to Christianity The Problem of Boundaries between Eastern and Western Europe 260 LECTURE SUGGESTIONS 1. Discuss the nature of Byzantine political organization and culture and how they affected the development of Eastern Europe. Byzantine political organization was based on a centralized monarchy supported by a trained bureaucracy educated in classical traditions. Local administrators were appointed by the central administration. Political ideology focused on the principle of a divinely authorized monarchy supported by elaborate court ritual. The Byzantines continued the use of Roman patterns of government as typified by the use of legal codes to organize society. Members of the military were recruited from the imperial population in return for grants of heritable land leading eventually to regional control by military commanders. There was a close relationship between the Orthodox Church and the state, with the emperor as head of church organization. Byzantine culture expressed itself in religious artifacts (churches, icons, liturgical music). The expansion of Byzantine culture northward was through the conversion of Kiev to Orthodox Christianity. The Russians also adopted the concepts of a divinely inspired monarchy with close relations to a state-controlled church. Church-related art forms came along with Orthodoxy. The Russians, however, were unable to adopt the Byzantine trained bureaucracy. 2. Compare and contrast the impact of Byzantium on Eastern Europe with the impact of the Islamic core on Africa and southern Asia. For Byzantine culture, see above. Both civilizations first spread their influence through missionaries; both civilizations passed on influences that produced centralized governments supported by the religious organization of the core cultures. Islam had a much greater impact than did Byzantium. The latter was limited to Eastern Europe while Islam spread into much of Asia and Africa. Byzantium’s influence was more tenuous since there was less direct continuity over time because it did not survive the postclassical period. In Russia, Byzantine influence was interrupted by the Mongol conquest. Islam has endured in all regions until the present. CLASS DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Evaluate the significance of the Byzantine Empire to the civilization of Europe. The Byzantine Empire was the birth place of Orthodox Christianity. This branch of Christianity spread through Eastern Erie westward, creating an alternative to Catholicism. Russia was also influenced by this empire, and claimed to be its heir. The Orthodox church and the civilization of Russia are the two most significant contributions to Europe. 2. Compare the development of civilization in eastern and western Europe. The West developed around Rome and its empire; likewise, the East branched from the Roman Empire during its decline. The religions also branched from the Romans. Rome developed by conquest, while trade was what spread to the East. 3. Compare Orthodox Christianity to Roman Catholicism. Byzantine culture, political organization, and economic orientation help to explain the rift between the eastern and western versions of Christianity. Different rituals grew from Greek and Latin versions of the Bible. Emperors resisted papal attempts to interfere in religious issues. Hostility greeted the effort of the Frankish king, Charlemagne, to be recognized as Roman emperor. The final break between the two churches occurred in 1054 over arguments about the type of bread used in the mass and celibacy of priests. Even though the two churches remained separate, they continued to share a common classical heritage. 261 4. Compare Byzantine and Chinese political organization. Like in Chinese political organization, Byzantine emperors were held to be ordained by God, being head of church as well as state. The emperor appointed bishops and passed religious and secular laws, and elaborate court rituals symbolized the ideals of a divinely inspired, all-powerful ruler. 5. Evaluate the reasons for the decline of the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire began to decline after the split between the East and the West. Turkish invaders pressed in on the eastern borders, eventually annihilating the emperor’s large army. Independent Slavic kingdoms in the Balkans, such as Serbia, and the Western leaders ignoring the requests for help from the East further established decline, and eventually the Turks gained complete control. 6. Describe the influence of the Byzantine Empire on the development of Russia. Princes were attracted to and borrowed several Byzantine ideas, such as the concept that a central ruler should have wide powers. They also borrowed Byzantine ceremonies and luxury. Orthodox Christianity penetrated into the culture of Russia and soon traditional practices such as polygamy were replaced with Christian practices. Russia also adopted Byzantine models in its art and architecture. 7. How did eastern Europe fall behind western Europe in terms of political development? Soon after the split between the East and the West, eastern Europe declined as Byzantine and Kievan rule fell. As this was going on, the “barbaric” West was developing its own strengths. Within a few centuries the dynamism of western Europe eclipsed that of eastern Europe, partially due to the strengthening of feudal monarchy around 1400, which provided stronger and more effective regional and national governments in the West. AUDIO/VISUAL TOOL KIT Video/Film Early Christianity and the Rise of the Church. Insight Media Enigma of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Insight Media Crusader. Films for the Humanities & Sciences Byzantium. Films for the Humanities & Sciences 262