CH6 Markets in action Outline I. Housing Markets and Rent Ceilings

advertisement

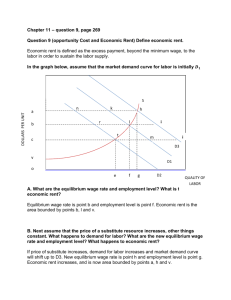

CH6 Markets in action Outline I. Housing Markets and Rent Ceilings A. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake in left 200,000 people homeless, yet the housing shortage vanished in one month. B. The Market Before and After the Earthquake 1. The short run supply curve shows the change in the quantity of housing supplied as the rent changes in the short run as the number of houses and apartments remains constant. Figure 6.1a shows that the earth shifted the short-run supply curve of housing leftward. After the earthquake, at the initial rent there was a shortage of housing. 2. A new, short run housing market equilibrium appeared in which the initial shortage of housing was eliminated by a rise in rents and an increase in the quantity of housing supplied moving up along the new, short run supply curve. 3. The long run supply curve reflects the quantity of housing that is available when enough time has elapsed for new housing to be built. In the long run, the supply of housing increased and the short-run supply curve shifted rightward, as shown in Figure 6.1b. 4. The long-run supply curve is perfectly elastic, so the long-run equilibrium price and quantity are the same as the pre-earthquake values (other things remaining the same). C. A Regulated Housing Market 1. A price ceiling is a regulation that makes it illegal to charge a price higher than a specified level. 2. When a price ceiling is applied to a housing market it is called a rent ceiling. a) If the rent ceiling is set above the equilibrium rental price for housing, the market attains equilibrium price and quantity as if there were no ceiling. b) If the rent ceiling is set below the equilibrium rental price for housing, the quantity of housing demanded by renters exceeds the quantity of housing supplied by landlords, resulting in a shortage of rental housing. 3. Because landlords cannot be forced to supply a greater quantity than they wish, the quantity of housing supplied at the rent ceiling is less than the quantity that would be supplied in an unregulated market. 4. Because the legal price cannot eliminate the shortage, other mechanisms operate. This results in increased search activity and encourages black markets to develop. D. Search Activity 1. The time spent looking for someone with whom to do business is called search activity. a) When a price is regulated and there is a shortage, search activity necessarily increases. b) Search activity is costly—the opportunity cost of housing equals its rent (regulated) plus the opportunity cost of the search activity (unregulated). 2. Because the quantity of housing is less than the quantity in an unregulated market, the opportunity cost of housing exceeds the unregulated rent—see Figure 6.2. E. Black Markets F. 1. A black market is an illegal market in which the price exceeds the legally imposed price ceiling. 2. A shortage of housing created by a price ceiling results a black market in housing. 3. Illegal arrangements are made between renters and landlords at rents above the rent ceiling—and generally above what the rent would have been in an unregulated market. Rent Ceilings Are Inefficient 1. A rent ceiling leads to an inefficient use of resources. a) The quantity of rental housing is less than the efficient quantity. b) This results in a deadweight loss to society, as illustrated in Figure 6.3. G. Are rent ceilings fair? 1. Using the “fair rules” criteria, anything that blocks voluntary exchange is inherently unfair. 2. Using the “fair outcomes” rule, it is fair if it can help the relatively poor and disadvantaged. a) Scarcity has not been eliminated—the resulting shortage from the price ceiling means that the market mechanism of price is no longer used to allocate housing. b) Rather, some other mechanism, like a lottery, or queuing, or some other form of discrimination. None of these methods of distribution favor the poor and disadvantaged. H. Rent Ceilings in Practice 1. Many of the world’s biggest cities use rent ceilings to allocate housing: New York, Paris, London, San Francisco. 2. Compared with housing markets in cities that do not use rent ceilings, reveals that in cities with rent controls: a) Housing shortages exist b) Some renters pay lower rents, but others must pay higher rents. c) Those that have lived in the city the longest are usually ones that get the lower rental rates. II. The Labor Market and the Minimum Wage A. New, labor-saving technologies become available every year, which mainly replace low-skilled labor. 1. The market responds with a decrease in the demand for low-skill labor, shown by a leftward shift of the demand curve in Figure 6.4a. 2. A new labor market equilibrium arises and the initial surplus of labor is eliminated by a fall in the wage. 3. In the long run a decrease in the supply of low-skill labor occurs as people get trained to do higher-skilled jobs, resulting in a leftward shift of the short-run supply curve shown in Figure 6.4b. 4. The long-run supply is perfectly elastic, so the long-run equilibrium wage rate is the same as the before the technological level changed (all else remaining the same). B. A Minimum Wage 1. A price floor is a regulation that makes it illegal to trade at a price lower than a specified level. 2. When a price floor is applied to labor markets, it is called a minimum wage. a) If the minimum wage is set below the equilibrium wage rate, it has no effect. The market works as if there were no minimum wage. b) If the minimum wage is set above the equilibrium wage rate, the quantity of labor supplied by workers exceeds the quantity demanded by employers. There is a surplus of labor. 3. Because employers cannot be forced to hire a greater quantity of labor than they wish, the quantity of labor hired at the minimum wage is less than the quantity that would be hired in an unregulated labor market. 4. Because the legal wage rate cannot eliminate the surplus, the minimum wage creates unemployment—Figure 6.5. D. The Inefficiency of a Minimum Wage 1. An unregulated market equilibrium means that everyone who is willing to work at the going market wage will find a job. 2. The minimum wage regulation means that a labor surplus will arise—some who are willing to work at the minimum wage will not be able to find a job. 3. This outcome creates a dead weight loss to society, as Figure 6.6 illustrates. Many people will spend extra time searching for and not finding work, and they would have been willing to work at the lower, unregulated wage. E. The Federal Minimum Wage and Its Effects 1. The United States has passed the Fair Standards Labor Act, which currently sets the minimum wage at $5.15 per hour. 2. This minimum wage has historically fluctuated between 35 percent and 50 percent of the average wage of production workers. 3. A study of wage and employment data by economists David Card and Alan Krueger (Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage Law, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995) recently suggested that minimum wage laws do not cause unemployment. 4. Other economists disagree and claim that ceteris paribus conditions were violated regarding: a) the timing of hiring decisions to raises in the minimum wage, or b) there were significant differences among regions studied. 5. F. Most economists believe that minimum wage laws do lead to more unemployment among unskilled younger workers. A Living Wage 1. Despite the likely increase in unemployment caused by a minimum wage, supporter of a higher minimum wage known as a “living wage” argue that individuals working 40 hours a week deserve enough pay to afford rental housing that is no more than 30 percent of their income. 2. Many city governments such as St. Louis, St. Paul, New Orleans, etc., have already imposed these laws on their own government employees. 3. The results will be the same as for the Federal minimum wage law, only with more intensity and greater deadweight loss. III. Taxes A. Who really pays the taxes? Demand and supply analysis shows how much of the tax burden the buyer and the seller share in the payment of a tax. 1. Tax incidence is the division of the burden of a tax between the buyer and the seller. a) Buyers respond to the price with the tax, because that is the price they must pay. b) Sellers respond to the price without the tax, because that is the price they receive. c) 2. The tax is like a wedge driven between the price paid and price received, altering the incentives facing both buyers and sellers. Tax on Sellers: Figure 6.7 shows how a new sales tax of $1.50 per carton of cigarettes placed on the sellers of cigarettes in New York City places a wedge between the price that buyers must pay ($4.00 per pack) and the price sellers actually receive after the tax ($2.50). a) The supply curve is shifted leftward. The vertical distance between the old and new supply curves is $1.50 at each and every quantity. This shift arises because the sellers are only willing to supply the same amount of cigarettes if they receive the same price after the tax is paid. b) The after-tax price that satisfies both the existing buyer’s demand curve and the new seller’s supply curve is $4.00 per pack. c) The new price is higher than the original price ($3.00 per pack), but not by the full amount of the tax. As a result, that the quantity of cigarettes sold is less than it was before the tax. d) A dead weight loss exists where potential gains from trade would have been enjoyed by society had the tax not been paid. However, both buyers and sellers bear some of the burden of the tax. 3. Tax on Buyers: Figure 6.8 shows how a new sales tax of $1.50 per carton of cigarettes placed on the buyers of cigarettes in New York City places a similar wedge between the price that buyers must pay and the price sellers actually receive after the tax. a) This time the demand curve is shifted leftward. The vertical distance between the old and new supply curves is $1.50 at each and every quantity because the buyers are only willing to purchase the same amount of cigarettes if they can pay the same price after the tax is paid. b) The after tax price that satisfies both the existing seller’s supply curve and the new buyer’s demand curve is at $4.00 per pack, just as before. c) Again, the new price is higher than the original price ($3.00 per pack), but not by the full amount of the tax. This result means that the quantity of cigarettes sold is less than it was before the tax, just like before. d) A dead weight loss still exists where potential gains from trade would have been enjoyed by society had the tax not been paid. Again, both buyers and sellers bear some of the burden of the tax. B. Equivalence of Tax on Buyers and Sellers 1. These two scenarios reveal that the effect of placing a tax on buyers generates the equivalent result as placing the same tax on buyers—the new equilibrium price and quantity are identical. 2. The tax is not necessarily split evenly across buyer and seller: a) Comparing the old price that buyers used to pay ($3.00) with the new price ($4.00), buyers must bear $1.00 of the tax for each pack sold. b) Comparing the old price received by sellers ($3.00) with the new price they used to receive ($2.50), the sellers bear only $0.50 of the tax for each pack. c) In this example, it is the buyers who bear the largest share of the burden imposed by the tax. C. Tax Division and Elasticity of Demand The division of the tax burden between buyer and seller depends on the elasticities of demand and supply. In extreme cases, the seller or the buyer pays the entire tax. 1. The buyer pays the entire tax if: a) Demand is perfectly inelastic (the demand curve is vertical). Figure 6.9a shows this scenario. b) Supply is perfectly elastic (the supply curve is horizontal). Figure 6.9b shows this scenario. 2. The seller pays the entire tax if: a) Demand is perfectly elastic (the demand curve is horizontal). Figure 6.10a shows this scenario. b) Supply is perfectly inelastic (the supply curve is vertical). Figure 6.10b shows this scenario. C. Taxes in Practice 1. Although no goods or services truly exhibit perfectly inelastic demand, governments often levy taxes on goods and services with very inelastic demand, such as alcohol, gasoline, or tobacco. a) After the tax is imposed in these cases, the quantity sold declines only minimally. b) This means the government can collect much larger tax revenues because it is able to place a tax on nearly the same quantity of goods sold as before the tax was imposed. D. Taxes and Efficiency 1. In general, imposing a tax creates a deadweight loss. 2. Figure 6.11 shows the deadweight loss created from a tax on CD players. IV. Subsidies and Quotas A. Harvest Fluctuations 1. The supply curve for farm products is heavily influenced by natural forces (weather, insects, etc.) beyond the control of farmers. 2. Once farmers have harvested their crop, they have no control over the quantity supplied. They move along the perfectly inelastic momentary supply curve. 3. These two characteristics combine to make the market for farm products very volatile. a) A poor harvest: Poor weather conditions shift the supply curve to the left, decreasing equilibrium quantity and increasing market price. This raises total farm revenues. Figure 6.12a shows the impact on market price and quantity from a decrease in the supply of wheat. b) A bumper crop: Ideal weather conditions shifts the supply curve to the right, increasing equilibrium quantity and decreasing market price. This decreases total farm revenues. Figure 6.12b shows the impact on market price and quantity from an increase in the supply of wheat. 4. The elasticity of demand for farm goods affects farm revenues: a) If the quantity sold and the revenues collected by farmers move in the opposite direction, the demand for wheat is inelastic (as was the case in the above example). b) If the quantity sold and the revenues collected by farmers move in the same direction, the demand for wheat is elastic. c) Avoid the fallacy of composition: Even if the total farmer revenues increase during a poor harvest, not all farmer will see an increase in revenues. 5. The government uses subsidies to control for large fluctuations in the momentary supply curves of farmers. a) A subsidy is a payment made by the government to a producer. b) Figure 6.13 shows how both the quantity sold and the price received by the sellers are higher after the subsidy. It also shows how the subsidy drives a wedge between the marginal benefit and marginal cost to society, resulting in a surplus of farm product and a dead weight loss. 6. The government also uses production quotas to control for large fluctuations in farmers’ momentary supply curves. a) A production quota is an upper limit to the quantity of a good that may be produced in a specific period of time. b) Figure 6.14 shows how both the quantity sold is lower and the price received by the sellers is higher after the production quota is in place. It also shows how the subsidy drives a wedge between the marginal benefit and marginal cost to society, resulting in a surplus of farm product and a dead weight loss. V. Markets for Illegal Goods A. The U.S. government prohibits trade of some goods, such as illegal drugs. Yet, a market still exists for these prohibited goods and services. B. A Market for Illegal Drugs 1. Prohibiting transactions in a good or service raises the cost of such trading between buyers and sellers. Figure 6.15 shows the demand and supply curves for illegal drugs. 2. Compared to an unrestricted market: a) If the penalty is levied on the seller, the penalty is added to the minimum price required for supplying the good or service. The supply curve shifts leftward, so that the vertical distance between the initial supply curve and the supply curve with the penalty equals the dollar value of the penalty. In this case, the equilibrium price of the product rises and the equilibrium quantity decreases. b) If the penalty is levied on the buyer, the penalty is subtracted from the maximum willingness to pay for the good. The demand curve shifts leftward, so that the vertical distance between the initial demand curve with the demand curve with the penalty equals the dollar value of the penalty. In this case, the equilibrium price of the product falls and the equilibrium quantity decreases. c) 3. If buyers and sellers face penalties, both the demand and supply curves shift leftward. If the shift in the supply curve is larger, the equilibrium price rises and quantity decreases; if the shift in the demand curve is larger, the price falls and quantity decreases; if the shifts are the same magnitude, the price is unchanged and the quantity decreases. The impact of the prohibition depends on how effectively the ban is policed and whether the penalty is levied on the buyer, the seller, or both. The resulting equilibrium quantity is less than the unregulated market equilibrium quantity. C. Legalizing and Taxing Drugs 1. A prohibited good can be legalized and then taxed so that, compared to free and untaxed trade, the price is higher and the quantity consumed is less. 2. A high tax rate would likely be necessary to decrease consumption to the level that occurs when trade is illegal. 3. A policy of legalizing and taxing a prohibited good or service has advantages and disadvantages. a) An advantage is that the government raises tax revenues, which can be used for education against the consuming the good or service. b) A disadvantage is that legalization may signal that use of the good is acceptable, which could increase demand for the product. In addition, if the demand for the product were inelastic, it would take a very high tax to reduce consumption to the same level that occurred with prohibition.