INTRODUCTION - Center for Invasive Plant Management

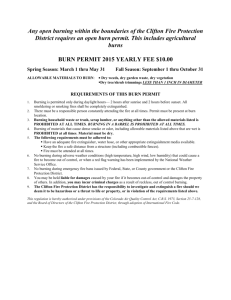

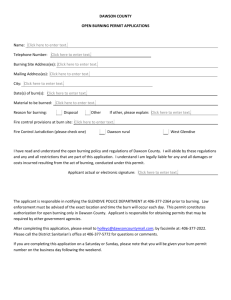

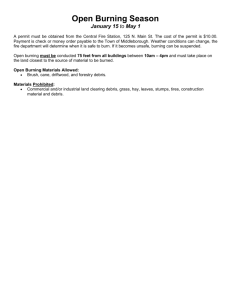

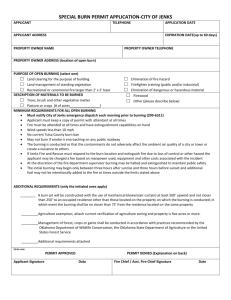

advertisement