disability, gender and the labour market in wales

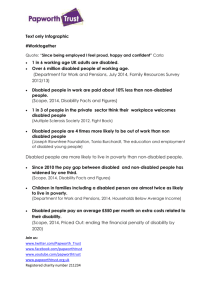

advertisement